The Unitarian Society

East Brunswick, NJ

May 5, 2019

Dr. Glen Thomas Rideout is the Director of Music and Worship at the First Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Ann Arbor. A Black, gay man, he wrote, not all that long ago, about an encounter he had with a white woman at General Assembly, the national gathering of Unitarian Universalists that happen every June. The thousands gathered had sung, just like we did this morning, There is More Love Somewhere, which is from the African American tradition.

The woman shared how she changed the words from “there is more love somewhere” to “there is more love right here,” because this reflected her experience of finding love and belonging within Unitarian Universalism. She asked, why, at GA, it wasn’t sung with those changed words.

Dr. Rideout, tired but willing, said, “Thank you for trusting me with that question,” and then continued his response. Here are his own words:

… I explained to her why I thought it was necessary — particularly with the music of people of color — that we enter and examine these songs with more curiosity than colonization.

I thanked her, and…I explained that it can be difficult to understand the lived experience of those who have trouble finding the evidence of love in their immediate vicinity; in their church; in their neighborhood; in their city; in their nation; even in their planet.

I thanked her, and I explained that for some who don’t share the privilege of perceiving love “right here,” moving toward that idea of privilege had become a vital practice of Black faith.

I offered that if we, as a spiritual community of Unitarian Universalists, populated by well-meaning people, are to mean anything to the lives and the deaths of people of color, we must begin by learning — not squelching — the forms of expression that arise from these living perspectives.

And she said, “Thank you. I’ve never heard it expressed that way. I’ve never understood it that way. And I will never sing it that same way again.”

More curiosity than colonization. That’s a powerful contrast.

What also caught my attention is this white woman’s response. Thoughtful. Thankful. Willing. Open. Curious. The exact opposite of most of the defensive, reactive responses from our Time For All Ages. The exact opposite of what Dr. Robin DiAngelo calls “white fragility.”

Dr. DiAngelo, an Associate Professor of Education at the University of Washington, is the best-selling author of a book based on a longstanding concept for which she coined the term, back in 2011, “white fragility.” Published by (Unitarian Universalism’s own) Beacon Press, it is currently at #3 (on the paperback, non-fiction list) on the New York Times Bestseller list and has garnered much attention far and wide.

Dr. DiAngelo has presented at General Assembly and is scheduled to present again this year. For a religious denomination that is majority white and declares that racial justice and dismantling white supremacy are crucial, her work is challenging, compelling, constructive – though not comfortable or comforting – and in my opinion, crucial.

So, just what IS white fragility?

Even if the term is new, the concept isn’t. Likely by any person of color recognizes the behavior, though probably fewer white people do, even well-meaning, well-intentioned, liberal and progressive white folks. It takes many forms. In my white experience, it is unavoidable and inevitable. And it is also workable.

When I say that it’s not a new concept, think of the passage from Dr. King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, where he takes to task white moderates, calling them – us? – a greater stumbling block than the KKK. He describes the white moderate as someone “who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” This devotion to order, as well as the preference for the absence of tension, are the bedrock of white fragility.

~~~

DiAngelo’s framework for understanding how race – and in particular, whiteness – operates has been clarifying and challenging and expanding for me. I raise it here, on Sunday morning, because I think it might be useful to you, whether you are white or a person of color. And because it can be helpful to us as a congregation that is majority white, but aspires to engage in racial justice work and to be welcoming and truly inclusive to people of color here, not just in our intention, but in our actual impact.

As we heard in this morning’s reading, Dr. DiAngelo posits that in our modern, post-civil rights society, there is a good/bad binary when it comes to racism. Racism is bad, so only bad people can be racist. If I am a good person, then I can’t be racist.

However, this false binary precludes us from seeing that good people can say or do things with racist implications or impacts all the time. And while it happens without diminishing our inherent worth or our essential goodness, it does seem to lead to white people becoming defensive and failing to see harm we cause. DiAngelo writes

Within this paradigm, to suggest that I am racist is to deliver a deep moral blow—a kind of character assassination. Having received this blow, I must defend my character, and that is where all my energy will go—to deflecting the charge, rather than reflecting on my behavior. In this way, the good/ bad binary makes it nearly impossible to talk to white people about racism, what it is, how it shapes all of us, and the inevitable ways that we are conditioned to participate in it.

And then she names the problem with this:

If we cannot discuss these dynamics or see ourselves within them, we cannot stop participating in racism.

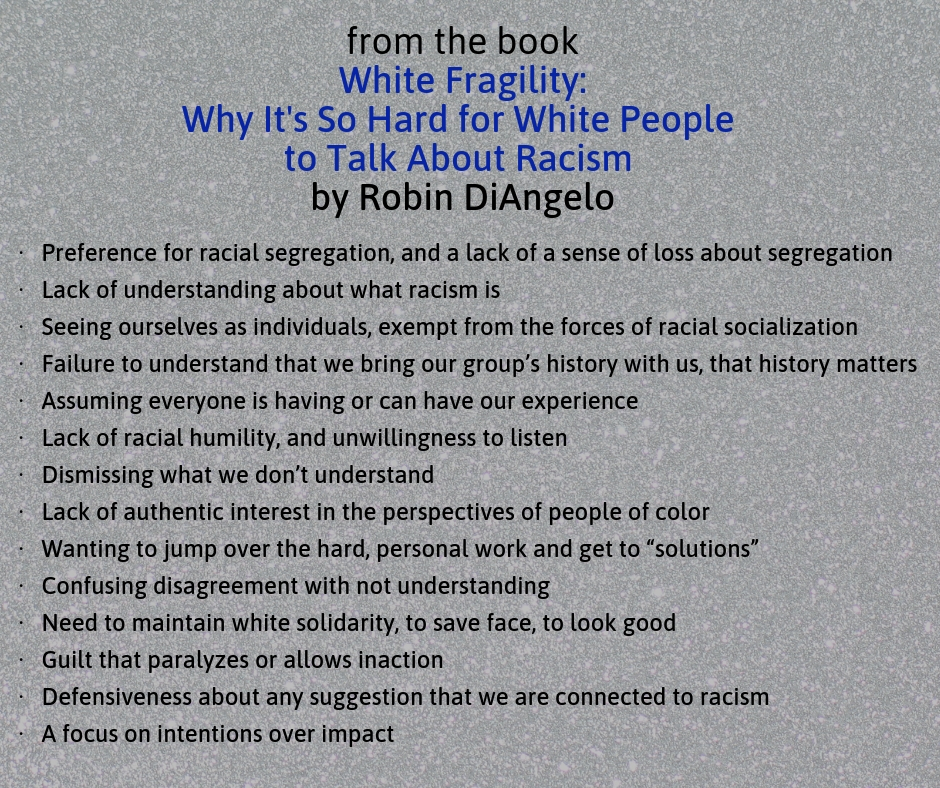

This defense of our character – and I am here speaking to other white folks in the room – expresses itself in recognizable ways, for which she uses the umbrella term, “white fragility.” DiAngelo has developed a list of qualities or behaviors that make up white fragility; it is included in your order of service. It’s too dense to recite in wholesale from the pulpit. I encourage you to take it home with you as a prompt for family conversations or personal reflection, being sure to pay attention to the reactions that arise within you as you do.

~~

Having just explored the second to last item on her list – “defensiveness about any suggestion that we are connected to racism” – I want to raise to you the last item: “a focus on intentions over impact.”

I want to raise it because some of what we use to form community, including in our covenant of right relations (the bullet point to assume the good intentions of others) can lead us to minimize harmful impacts.

I want to raise it because I think that if we are going to engage in the dismantling of white supremacy culture and the marginalization of any group of people, we have to start paying attention the impact of our actions, not just our intentions.

A simple example to illustrate the point: I accidentally step on someone else’s toe. I didn’t intend to, yet I hurt them. The impact is pain, perhaps injury. It is not enough to say that I didn’t mean it. To be in right relationship, I must tend to the pain I caused. Pretty straightforward in that situation. Yet racism coupled with white fragility makes it more convoluted.

I remember that the first time I was told that a phrase I had just used was racist, I felt the sting of being called out. Racist? Me? That simple term? Then I listened and learned that the word “gyp” – as in, being tricked out of something – is based on a racist stereotype of gypsies – the Roma people – as deceptive thieves. Though I did not intend harm, I was thankful to be informed that was the impact of my use of such a phrase, so that I could choose a different way to convey the same meaning.

~~~

My white colleague, Molly Housh Gordon’s, who serves our Unitarian Universalist congregation in Columbia, Missouri, describes white fragility as,

“when white people cannot bear to face conversations about race because of the pain of becoming aware of deeply unjust circumstances that people of color have endured with their lives.”

She goes on to acknowledge that other forms of fragility exist, all of which are located in any identity that has privilege in our society: male fragility, able-bodied fragility, hetero- fragility, wealth fragility, cisgender fragility, and more.

Notice your own internal response to that list, especially if you hold one of those identities.

Do you notice a defensiveness rising, a wish to argue, or rationalize?

Do you see rising within you a response like, “well, what am I supposed to do, feel guilty?”

or an impulse to deflect?

Do you want to talk about good intentions, those of others or your own, rather than to have to sit with the reality of the impact of whiteness – my whiteness, your whiteness if you are white?

I raise up all these possible reactions because I know them personally and intimately. Intellectually, I share Dr. DiAngelo’s suppositions about how race operates in America; and still I find myself emotionally wanting to argue against some of her points.

For me, though I’m not proud of it, these suppositions sometimes feel like accusations. Then I realize, that’s on me – she’s naming a challenging reality, not making an accusation. That emotional reception, the one that contorts it into an “accusation,” that’s my responsibility to own. And I can choose a different response; I can choose to be curious.

Rev. Housh Gordon has a playful, but effective, way of thinking about the white fragility response. She calls to mind a comedy sketch popular from Key and Peele of Luther, the Anger Translator. At the 2015 White House Correspondent’s Dinner, the comedian Keegan-Michael Key played Obama’s Anger Translator in real time, standing behind the president as Obama said everything in measured, politic tones. Luther would rant and rave in a way that would never be allowed as a leader of color in our society.

Rev. Housh Gordon feels that white fragility is not an anger translator, but a SHAME translator. So when

A person of color says: “Hey that thing you participated in hurt me.” And from the shame translator on my shoulder I hear: “You are a bad person unworthy of love.”

Or someone writes: “You received a head start in life because of the color of your skin.” And from the shame translator on my shoulder I hear: “You deserve none of the good or joy you have found in this life.”

Rev. Housh Gordon concluded

These shame translations are lies – the have nothing to do with what is being said or meant, and yet until we build the resilience to override those creeping voices of shame and self-doubt with curiosity and humility, they are powerful enough to shut down transformation and conversation the world over. They have done it for centuries.

What if, instead of shame, we bring curiosity to such circumstances, like the white woman from the story by Dr. Rideout? This is, of course, not a one-time task, but an ongoing practice; and even a life-long calling. It is for this reason that a small group of congregants here, at this time all white, and I are hoping to put together a covenantal book discussion group next year, to delve more deeply into this worthy work. Perhaps you will join us?

~~~

DiAngelo describes a situation that I think many of us can recognize, perhaps even from interactions here in this congregation:

[it’s] the big family dinner at which Uncle Bob says something racially offensive. Everyone cringes but no one challenges him because nobody wants to ruin the dinner. Or the party where someone tells a racist joke but we keep silent because we don’t want to be accused of being too politically correct and be told to lighten up.

These are examples of what DiAngelo calls white solidarity (fourth from the bottom on the printed list in your order of service), a term that raises all kinds of defensive alarms for me, because it sounds like the behavior of groups like the KKK or the people with tiki torches in Charlottesville.

But I have also observed in myself when I have kept quiet instead of speaking up. So I’m trying to stay curious, rather than let that shame translator be what feeds my reaction.

In those examples, we could trade out racist here for sexist, and a similar dynamic is at play.

I have observed in such situations, in myself and in others, that there is a process of rationalizing staying silent by convincing myself that the person who just said the racist or sexist thing had good intentions, just problematic expression. I have given that benefit of the doubt around good intention more weight than the possible impact of creating an unwelcoming environment or causing outright harm. I know I am not alone as I have spoken with some of you who have been in this struggle. I think this is something worthy of our grappling with, individually and together as a community.

I want to close with these wise words from Dr. DiAngelo, which she speaks as a white person, with resonance around any of our privileged identities:

I did not set this system up, but it does unfairly benefit me, I do use it to my advantage, and I am responsible for interrupting it. I need to work hard to change my role in this system, but I can’t do it alone. This understanding leads me to gratitude when others help me.

And these gentle words from Rev. Joe Cherry, which we heard in the prayer:

May we be bold enough to step into our discomfort,

brave enough to be clumsy there,

loving enough to forgive ourselves and others.

Amen. Blessed be

Let the Mighty God bless you, dear. I believe living in harmony with yourself and with others independently on skin color, thoughts, personal point of view concerning this or that thing to be like a green light on the way to the God. Have read your post with a great pleasure and am looking forward to the new ones, thanks.