The Life and Death of Lee Hawkins

First Unitarian Church of Albuquerque

July 14, 2019

A quarter century ago, I asked the coordinator of my grandmother’s hospice care, how my grandmother was doing – not medically, but spiritually. She said simply, respecting both my grandmother’s confidentiality and my grief-as-curiosity,

“As we live, so we die.”

This was unfortunate for my grandmother, who barely topped five feet but intimidated the beejeezus out of nearly anyone, including her progeny, with her need for control and insistence on her rightness in the world. Dying was no easy path for her.

Today I want to tell you about a different older woman whom I also loved. I want to tell you about a different way to encounter dying and death. I want to tell you about someone who, when the time was right, couldn’t wait to be the hummingbird.

I want to tell you about Eleanor “Lee” Hawkins.

In the process of becoming a Unitarian Universalist minister, one must go before the daunting Ministerial Fellowship Committee. When I was preparing for that august meeting, word on the street was that a commonly posed question was a request to name a Unitarian or Universalist or Unitarian Universalist hero from each of the last four centuries.” I knew that I would name Lee as my 21st century choice.

I tell you about Lee as a talisman for myself, a gesture as part of my own spiritual practice of befriending death, my inelegant attempts to live into that line from our reading: “the tenderness yet to come.” That poem is our reading today because Lee left instructions for me to read it at her memorial service in 2014.

Lee was, indeed, that hummingbird. In 2004, a full decade before she died, when her husband was dying at home, he called out to Lee from the bedroom. It was time. He told her that he was at death’s door. Lee went to him full of devoted love – they had been married for decades upon decades and were still effervescent with their adoration for each other. She sat on the bed, and asked, “Rog – what’s it like?”

Minister or lay person, churched or so-called “unchurched,” organized or free-range, death is the great leveler, and there is much for us to learn and gain and be enriched by these stories and acts of witness. So, I am telling you about Lee because I want her witness in the world – dead as she is now — to enliven and expand your notions of what is to be human in this aching world that always, without exception, ends in death. In this way, I make good on a promise I made to her: to tell the story of her death and her life.

~~~

Born in California, Lee lived much of her life in Staten Island, active in the UU congregation there. Then, for the last twenty or so years of her life, she was in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she and I were members of the same UU congregation.

As I understand it, for most of her adult life, Lee spoke of her intention to be aware and in control at the end of her life. Yes, documents: a will, advanced directive, all that, yes. But conversations, too, with her family: extraordinary medical interventions, her vision of what a good life is and also what a good death might be.

Control is the wrong word, conveys the wrong meaning, because she was not controlling death in the way too often depicted in our death-adverse culture – controlling it by keeping it at bay. What I mean is being in relationship to death, being willing to surrender to death, when the right time comes.

This intention was part and particle of her deeply rational, deeply kind, deeply political being. As she gained years, having not succumbed to the vagaries, surprises, and tragedies so many of us humans experience, she prepared for the possibility of dying of old age on her terms.

This impulse was not born of that depression that can accompany the aging process, which is often so much about losing – losing capacities, losing friends, losing out on experiences in the wider world – though anticipating this, and eventually experiencing it, did inform some of the timing and texture Lee’s choices.

While her choice was a personal and private one, shared with her family and closest beloveds, Lee was public about her plans. When the time came – and she did not know exactly what time that was, but when it did – she would “manage her own death.” That’s the phrase she chose to describe her actions. “Manage her own death:” facing towards it, not away.

She researched her options methodically and with attention to how her choice might impact her family and community. She made her decisions in relationship with her adult children – not seeking their approval, but informing them, bringing them along, gaining their assent. In the end, at the age of 90, still without terminal diagnosis, living in a body weakening and a mind beginning to forget, after significant research, she made it clear that, when the time came, she would stop eating and drinking.

Five springs ago, Lee was living at home, one side of her body weakened so much she could barely use it. She found herself facing the reality she might fall and lose her autonomy.

In June, I heard from a mutual friend: it was nearly “time.”

Like so many of her friends did at this time, I brought dinner over to Lee. Each of us did this, knowing we were not just bringing food – Lee barely had any hunger at this point – but coming to spend time with her. We were having what each of us knew would be our last conversation, our good-bye. Lee took such delight in the gift of knowingly having a last conversation – she said it was one of the best parts of being public about deciding to manage her death.

That summer I was working as a hospital chaplain intern at a Trauma I hospital — part of preparation for the ministry that all Unitarian Universalist ministers go through. While “eating” with Lee, I asked her if she would be interested in meeting with my CPE peers and supervisor. Lee had been a school teacher for decades and never lost that drive to teach. Indeed, she jumped at the chance.

Seven of us – representing multiple faith traditions — spent a few hours with her, listening to and learning from a person choosing to encounter death with such intention. One of my favorite moments from that meeting is Lee chiding the ones who didn’t ask questions – “how could they pass up this opportunity?” she queried, impatient at their timidity.

Ever committed to teaching and to public witness of encountering death without fear (or, from her humanist side, superstition), the year before she had taken part in a community dialogue about death. She had been interviewed by the local newspaper reporter about her plans, engaging in an intimate and frank dialogue that was published in 2013.

By late August, Lee had intentionally stopped eating and drinking. Surrounded by her three adult children, moving towards death, Lee invited (and her children allowed), that same local newspaper reporter and photographer to be present, to record in word and photo, the process of her dying and her death, which took place on September 2, 2014.

The narrative and photo-narrative was published to much praise… and much condemnation. We have, as a society, for the most part, hidden death away. So, when a person like Lee, or a journalist, or a newspaper, decides to stop hiding, strong feelings erupt.

~~~

Not many of us are ready for death. I am not ready for death.

But it does not much matter, our readiness, our assent. Death comes. Wise people tell us that if we live our lives knowing that we are going to die – that we are in many ways, always dying, each moment – that our lived days will be fuller and more precious. A hard lesson to take in, but our ministries, and our very lives, depend upon it.

While you or I may not make the same choices as Lee made, I invite you to consider the invitation her choices extend to us all: to bring intentionality to our lives by bringing intentionality to our deaths before they happen. To hold conversations with those nearest us, with someone here in this room, even with strangers. To engage in a process of discernment about the end of life – about the end of your life – and then share what you learn with those nearest and dearest to you. While some say to contemplate death is a morbid preoccupation, it’s actually true that there is a way for such ruminations and meditations to be… enlivening.

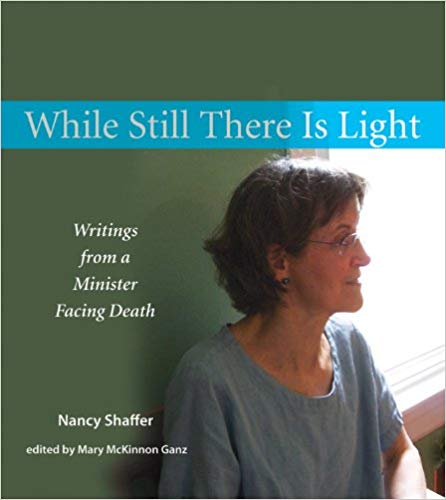

Let me close with another UU voice who has blessed us with reflections upon her own death. The Rev. Nancy Shaffer was diagnosed with a brain tumor which eventually, and far too soon, took her life on June 5, 2012. Nancy kept a journal with the intention of having her reflections published, which they were, under the title, While Still There Is Light:

This is not lost on me:

Given that I have a tumor

That – I am told – will someday kill me

I have also the advantage

That I must reflect now –

While I am alive –

On the meaning of my life

And how I want to leave it.

I might have died quickly.

This is harder, perhaps,

But exquisitely richer:

I get to grieve for my own self.

How tender and not-to-be-missed

Is this?

May each of us be more able to face death: that of loved ones — even our own — to know peace and ease, and perhaps even the curiosity of Mary Oliver’s hummingbird.

Amen. Blessed be.