February 11, 2024

First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

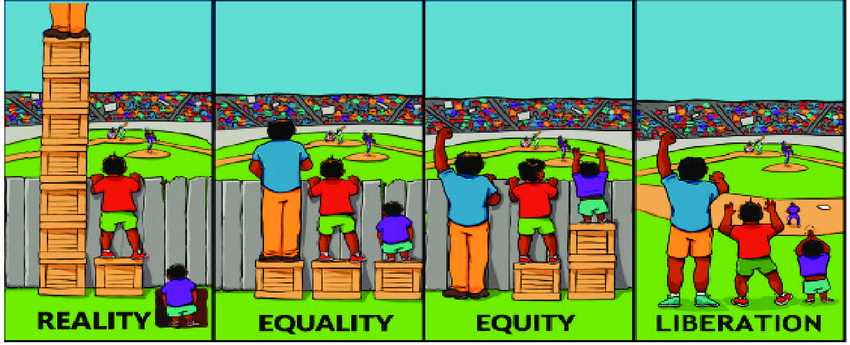

Perhaps you have seen the graphic depiction of the difference between equality and equity? There are many versions of it. The one I am thinking of at the moment has three different people – we see their backs – attempting to look over a fence at a baseball game happening on the other side.

Each of the three are different heights – one is really tall and can see over the fence. One is medium height and must stand on their tip-toes to see over the fence. The third person is of a height that no matter what they do, on their own they are precluded from seeing. That’s the first frame of the graphic.

In the second frame, which is intended to depict equality, all three individuals are given boxes, all the same size, to stand on as they watch over the fence. The tall one, who could already see just fine, has an even clearer view. The middle-height person now does not have to strain to see the ball game. And the shortest person still cannot see for even though they are higher with the boost from the box, it’s not sufficient. This depicts equality because all three got the same solution to what was perceived to be the same problem.

The third frame is intended to depict equity. It’s the same three individuals with their same three different heights. The solution is that the tall person is given no box to stand on because they are already viewing the game just fine. The second person receives a box – the same one from the equality solution – and is watching the game just fine. And the third person – the short one – is standing on two boxes stacked one upon each other…and is now, finally, able to watch the game just fine. This frame is meant to depict equity – different solutions produce equal access.

As we learned in the Time for All Ages that not everybody needs a bandaid for their wrist, not everyone needs the same size box to ensure that we all have equitable access to life. Some of us need a bandaid for our wrist, others of us need one for our knee and others need not a bandaid, but a cast or sling.

Yet, sometimes, we keep trying to hand out the same size box, not recognizing that it’s not fair. Sometimes, we keep handing out wrist band-aids, not recognizing that it’s not fair. Kind of like when we did our fire drill last fall and learned that while everyone can theoretically leave out of any door in case of an emergency, we don’t have equitable access: in the sanctuary folks who use wheelchairs and walkers are asked to wait in the narthex for emergency personnel to assist them in fully exiting the building, while those in the sanctuary without mobility challenges walk down the stairs and gather at a safe distance from the building.

There are all kinds of old buildings ~ real and metaphorical ~ that need our attention as we strive for equity and justice.

As you heard in this morning’s reading, Isabel Wilkerson, in her book, Caste, uses the imagery of an old, worn house to convey the structural inequities she calls the universal caste system – one that takes different shapes in different cultures. She writes

America is an old house. We can never declare the work over. Wind, flood, drought, and human upheavals batter a structure that is already fighting whatever flaws were left unattended in the original foundation. When you live in an old house, you may not want to go into the basement after a storm to see what the rains have wrought. Choose not to look, however, at your own peril. The owner of an old house knows that whatever you are ignoring will never go away. Whatever is lurking will fester whether you choose to look or not. Ignorance is no protection from the consequences of inaction. Whatever you are wishing away will gnaw at you until you gather the courage to face what you would rather not see.

Caste: On the Origin of our Discontents, Isabel Wilkerson

There is a movie based on that book. The movie is called Origin and is directed by Ava Duvernay, whom I believe is an American gift of a movie director for the 21st century if we have any. As its closing monologue, the movie uses some words from the book ~ the very same words that we used in our reading.

If you have not yet seen the movie, I commend it to you. It did not get Oscar attention, but that should not deter you. Like the book, the movie makes a complex, and perhaps even counterintuitive, concept accessible and easier to understand. The movie is not a documentary; it is good story-telling, combining losses from WIlkerson’s own life and her brilliant work that has enriched our understanding of ourselves. (Yes, I am a fan.)

~~~

There is a story here at FUUSB that has caught my attention before I even officially arrived here. It’s one that I am surprised we don’t talk about much. It is the 2022 donation of $50,000 by First UU towards the founding of the Richard Kemp Center. $50,000. Not an act of charity, but as I have come to understand it: an act of justice and equity.

If this is news to you, I’m not surprised. There was a letter that went out from the board to the congregation in July 2022, after the Richard Kemp Center made a public announcement. But I have been curious about how little we talk about this. I have been curious how those who do talk about it, what narrative they convey. I wonder if there is consensus about the narrative within our congregation. And I wonder if there is consensus about the narrative outside of the congregation.

The Richard Kemp Center, if you are not familiar with it, is a Black-led, Black-empowerment community organization, right here in Burlington. It is both relatively new and long in the making, the love and brain child of the Vermont Racial Justice Alliance and supporters of the vision that for Black people to thrive in Burlington (and Vermont) there must be more culturally-empowering spaces. The center is named after a beloved and respected member of the Burlington community, Richard Kemp, himself African American, and a much cherished member of this very congregation who died in 2021.

When I was learning about this congregation during the search process, I was really impressed with the board’s choice to pass on such a large amount of money in this way. I learned that it was a proposal by the congregation’s Racial Justice Team, which asked the board to consider this request as a form of taking seriously the congregation’s unanimous vote in February, 2022 (two years ago) to live into the 8th Principle, which asks us to dismantle systemic oppressions, including racism, in ourselves and in our institutions.

Here are some of the words from their proposal to the board:

An essential tenet of social justice work is being in meaningful relationship with the people directly affected by the oppression and injustice you want to address. Without such a meaningful relationship, our efforts at social justice are likely to be misguided and perhaps even harmful. The Racial Justice Team has, for the past year, had a goal of building a relationship between FUUSB and the Vermont Racial Justice Alliance. The Alliance is a well-established, BIPOC-led, anti-racism organization in Vermont.

I agree. If we are not in relationship with each other and with community partners, it does not matter what our vision is. This is true on all fronts, but most especially I think when it comes to addressing systemic racism, when it comes to addressing the peculiar and particular anti-Blackness that seems to pervade our American society, and is very much present here in Vermont.

You might remember that during the pandemic, the congregation had received funds from the federal government. PPP – Payroll Protection Program. We received these funds at a time when we had not yet experienced the deleterious effects of the pandemic – in that first year or year and a half, our finances were solid. And then the PPP funds came in, first as a loan, then changed into a flat out grant with no obligation to repay.

The Racial Justice Team saw an opportunity for us to live out our values – not just around the 8th Principle, but around justice and equity, which was then, and still is now, our second Principle: “Justice, equity and compassion in human relations.”

The RJT had been reading what was being reported in the press: the PPP program was being shown to favor larger, more established, and predominantly white organizations. This included those groups with pre-existing relationships with banks that could help them quickly turn around the required application. Yes, that is a description of the system within which our congregation exists. The RJT’s proposal stated

Like almost all forms of white privilege, we did not ask to be favored in this way and it’s not our fault that the system put us at an advantage. But we have a responsibility to use our privilege in a way that helps to level the playing field and correct the advantage we’ve been given.

Do you hear the resonance in this language of their proposal and how Isabel Wilkerson talks about the inequities she names a caste system? Here are Wilkerson’s words:

“Not one of us was here when this house was built. Our immediate ancestors may have had nothing to do with it, but here we are, the current occupants of a property with stress cracks and bowed walls and fissures built into the foundation. We are the heirs to whatever is right or wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars or joists, but they are ours to deal with now.”

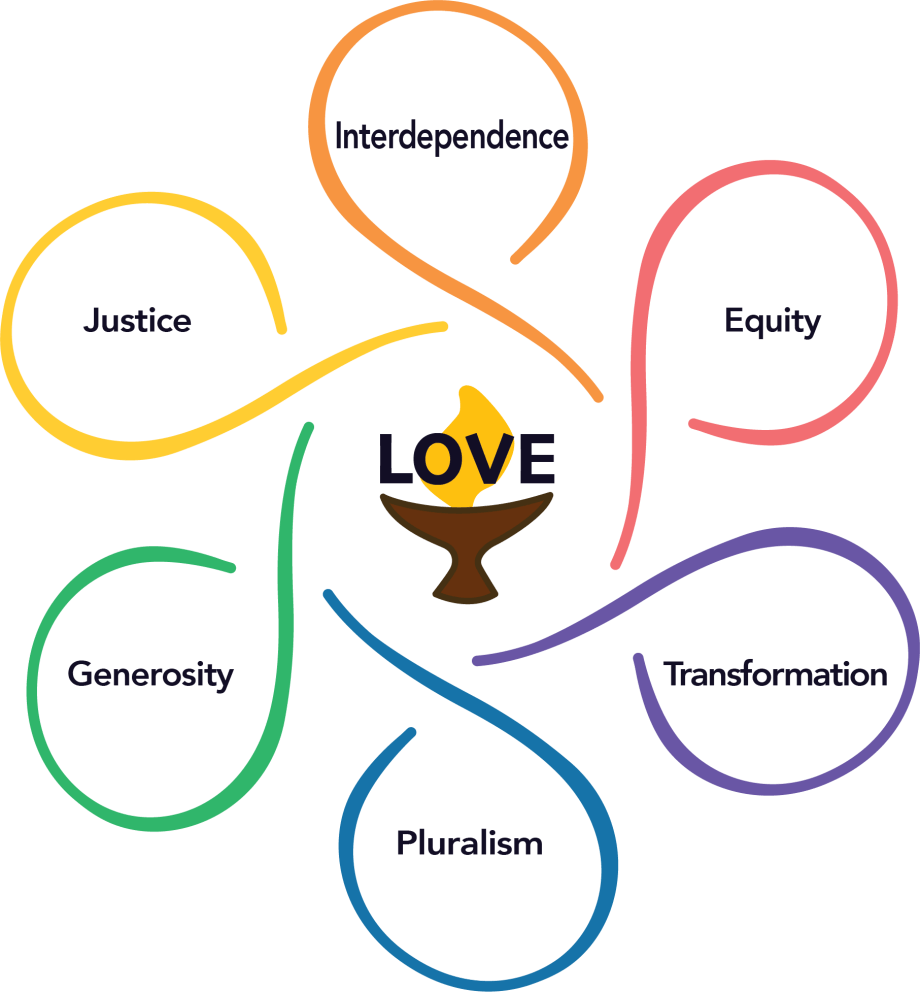

Justice and equity are part of the Principles of our Unitarian Universalism. Justice always has been included – it’s mentioned in the fourth of the six original Principles when Unitarians and Universalists came together in 1961. Equity joined the party later, in 1985. And as our faith movement shifts from Principles to Values, both of these concepts figure even more prominently and with more texture added to what we mean when we use these words.

In the proposed new language, with its seven values, this is how justice and equity are described. First justice:

We work to be diverse multicultural Beloved Communities where all thrive. We covenant to dismantle racism and all forms of systemic oppression. We support the use of inclusive democratic processes to make decisions within our congregations, our Association, and society at large

And then Equity:

We declare that every person has the right to flourish with inherent dignity and Worthiness. We covenant to use our time, wisdom, attention, and money to build and sustain fully accessible and inclusive communities.

Each value has a brief description of what we Unitarian Universalists mean by it and then a covenant statement of how we UUs embody that value. Two parts, meant to help us be more accountable to the values that guide our lives.

Both parts of the description are important. First, what do WE mean by the value? This is important to name, because lots of people use the word justice or equity and they don’t mean what we necessarily mean.

So we Unitarian Universalists say it means, in the case of justice:

to work to be diverse multicultural Beloved Communities where all thrive.

And we covenant to actualize this value in the following way:

dismantle racism and all forms of systemic oppression. We support the use of inclusive democratic processes to make decisions within our congregations, our Association, and society at large.

Others might choose to achieve justice in other ways, but this is how we are saying we will do it as Unitarian Universalists. Same for Equity. We describe the value as a declaration that

every person has the right to flourish with inherent dignity and worthiness.

Then we say what that value asks ~ requires ~ of us:

use of our time, attention, and money to build and sustain accessible and inclusive communities.

Reflecting on those values, I see just how audacious that passing on of $50,000 to a Black-led community organization is. Those PPP funds were relatively easy for us as an established institution and for us, a majority-white organization, to gain access to. And we chose to pass them along to “build and sustain [an] accessible and inclusive” community space – in this case, to give 10% of the seed money to build a community center by and for Black people in the greater Burlington area. That is something to be proud of.

When we have our financial worries and woes, as we will always have, our pride in this action can keep us company and sustain our spirits, knowing that we chose our values over comfort, knowing that having done so yesterday, we are more likely to do it today and tomorrow.

It matters that we understand the passing along of that money not as an act of charity, but one of justice and equity in relationship with a community partner. It matters that we understand it as living into our values and principles, even if it causes us some financial heartburn. It matters that we recognize that in making that choice, the leadership of this congregation was building a new way (as we are just about to sing); was being a part of working to be free of, yes, hate and greed and jealousy, but also the fetters of systemic racism. It matters that we acknowledge that putting love at the center of our actions has inconvenient consequences and sometimes painful sacrifices; and also, benefits beyond our capacity to design them, for that is what comes from bending the moral arc of the universe towards justice.

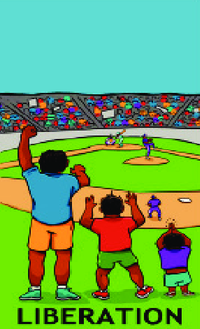

At the start of this sermon, I described to you a graphic representation of the difference between equality and equity – those three people of different heights and the different solutions. What I described was the original version, created by Craig Froehle.

Over the years, many people have been inspired by this learning aide. Many have identified its shortcomings; some have adapted it. I’m thankful to Mary Beth, today’s Worship Associate, for turning me onto some of the more creative versions that have emerged over the years: one with bicycles and wheelchairs; one with shoes. Some depict access not to a ball game, but to apples growing on a tree.

There’s one that adds a fourth frame. It depicts those same three individuals, all their different body heights, still watching that baseball game. But in this frame, the fence has been dismantled. There is no more barrier to enjoying the game: it is available to all. This one is called Liberation.

We might call it Beloved Community.