[the Time for All Ages at the start of this worship service is referenced throughout this sermon and can be read here, in case it’s helpful]

Who here knows the Far Side – that cartoon by Gary Larson?

These typically one-frame cartoons were commentary on absurdity. I am thinking of one in particular: a spaceship has landed and three aliens have just emerged. There is a human farmer, Roy, who is reaching out his right hand to shake what he thinks is the alien’s hand. However, what just so happens to look to Roy like four fingers and a thumb is actually the alien’s head. Thus, without meaning to, Roy causes the total annihilation of our planet.

His intent doesn’t match the impact.

Some of you might remember a sermon I gave this past September. It was on the book by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg called On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World. As part of that worship service, as I walked up to the pulpit, James and I collided and he fell. It looked like I had tripped him and then didn’t really acknowledge it, going on about the business of giving the sermon. Though, by the end of the sermon, given that I was talking about making amends, I apologized.

Yes, a pratfall. Intentionally planned and dramatically executed. I can’t tell you how many people approached me afterwards, convinced it was real. I felt like I had to apologize to each and every one of them for the impact of such persuasive staging – they were needlessly worried about James (and perhaps about the relationship between the new minister and the music director).

It would be wonderful if it were only in cartoons that our intent and impact don’t match.

But that’s not how the world, and human interactions, work – particularly ones where there are power differentials and systemic oppression. Yet still, some of us, especially those of us with cultural or social privilege, will lean on our intention too much.

If we are to live into the 8th Principle, if we are to live into our commitment to dismantle systems of oppression, including racism, in ourselves and in our institutions, we must pay attention not only to our intention; we must not only assume good intentions when harm is done or conflict emerges; we must do that AND we must, in at least equal measure, tend to the impact of our actions.

And in doing so, we must learn, when someone invites us to see the impact of our words or actions (or invites us to see the smudge that is on our face), to see their feedback for the gift it is, rather than defending against the information, rather than weaponizing our embarrassment, rather than gaslighting.

I want to tell you the tale of three hymns, two of which we are singing today, as a way to explore the relationship between intent and impact.

~~

Maybe you know the story behind this hymn, familiar to the congregation – the one we just sang. Originally it had a different title, one that used the word “standing” for the concept of “showing up on behalf of:” Standing on the Side of Love.

At 2016’s General Assembly, it seemed like every song sung used a walking or standing metaphor. Standing on the Side of Love, #1014. One More Step, #168. Guide My Feet #348. Rank by Rank #358. For the people who walk or stand without thought, it went unnoticed.

But for those among us who use walkers and scooters and wheelchairs and crutches, the impact was exclusion. Some disabled folks spoke up. They said something like, “you’ve got a smudge on your face.” They said something like, hey, it’s okay to use walking or standing metaphors every once-in-awhile, but this much? Without reference to other ways people move in the world or to show up?

The composer of the hymn, Jason Shelton, chose, rather than to defend the use of the metaphor that worked so beautifully, to listen. He did so to understand, not necessarily agree. And it turned out, as happens to people who are willing to become wise, that he was moved by a truth that did not make sense to his own lived experience and he let it change his world. And he let it change the lyrics and title of a song.

It’s like he was the character at the end of our Time For All Ages, he said

“I have something on my face? I have ableist privilege that is impacting my lyric choices? Oh, thank you for telling me. I’ve been washing it away, bit by bit, but I guess some of it is stickier than I thought. I really appreciate you’re letting me know. Would you be willing to help me wash my face? “

He let go of his perfect song that turned out to be perfect for only some. Eventually, he found the new song, with the new lyrics and new title, one that we all can sing and feel included: Answering the Call of Love.

~~~

There is another song in the same hymnal – an energetic, amazing song, written by the late Harry Belefante. The one we are not singing today. This song is going through a similar process as Answering the Call to Love, though it’s more complicated, because the composer is dead, and no community consensus on a resolution has, as of yet, been found. You can read more about this process in this write-up from Rev. Kimberley Debus.

It turns out that in Turn the World Around, there is a phrase that some say sounds like a nonsense phrase. In fact, that’s what Harry Belafonte thought it was – a nonsense phrase he heard when growing up on the island of Jamaica. But it turns out that, if you speak to some Jamaican UUs, we learn that the phrase sounds awfully like a homophobic slur. So much so that some refuse to be in the room when it is sung.

Before he died, one of these Jamaican UUs asked Belafonte about the phrase. That is when he said that he didn’t realize that phrase held that derogatory meaning. A version of “that was not my intention.”

And then Belafonte said, you UUs shouldn’t sing it. Which, to my ears, says that Belafonte recognized that it did not matter what his intention was: the impact was harm and harm should not be continued. And so, not out of political correctness or the desire to be woke, but out of the value to care for one another, we, too, can choose to not sing that song with that slur.

This is a live topic among religious professionals right now. Some are saying we cannot sing the song at all. Some are saying we can sing the song with a lyric change. Some are saying that if we choose to sing the song with the lyric change, we must tell the story so that more people learn not to cause harm inadvertently.

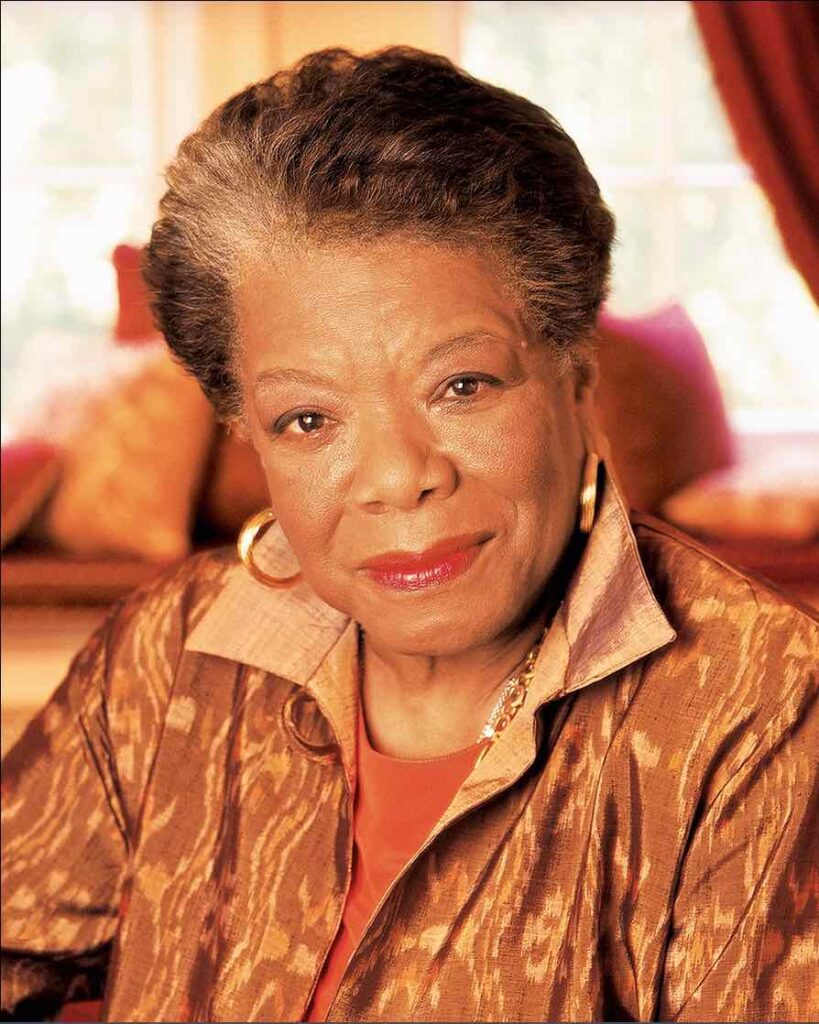

This is one of many ways we can practice the accountability named not only in the 8th Principle, but in the new Values proposed and being voted on at this June’s General Assembly. I believe it was Maya Angelou who said:

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better.”

More to come after our spiritual practices.

Part II

Before I talk about the third hymn, which we will sing when the sermon concludes, I want to connect us with our congregational covenant. You can find it on our website:

We gather together with the intention of creating a vibrant, healthy, liberal religious community. To this end, we make the following promises to each other:

To come with open minds and hearts so that we can welcome new ideas, new people and new possibilities.

To listen carefully to each other, to speak openly and respectfully, and to assume good intentions, especially in times of disagreement.

To participate actively in the life of the Society by being present, serving/volunteering, and providing financial support.

We recognize that there will be times when we will fall short of these ideals. We will be accountable to each other and forgiving of each other.

I have high praise for this covenant. I think it’s strong. I think that if kept at the forefront of our hearts and minds when we hold meetings or chalice circles or debate the worthiness of any decision, I think it is a good guide.

I also believe that since it’s been over a decade since it was adopted by the congregation and given how fast time moves, it makes sense that it might need some tweaking in order to stay relevant.

One of the things I have observed in the Unitarian Universalist Universe is that we are paying attention to how to deepen our sense of what it means to be in covenant with one another. And in our more recent attempts to ameliorate the influence of white supremacy and other supremacist cultures in our midst, we have been called to begin to pay more attention to the impact of our actions than to our intentions.

As such, more recent covenants include attention to impact, not just intention. More and more Unitarian Universalist covenants are moving from phrases like “assume good intentions” to phrasing like “Paying attention not only to intention, but the impact of our words/actions.” And whenever it is time for this congregation to review and refresh our covenant, I hope we will take this into account.

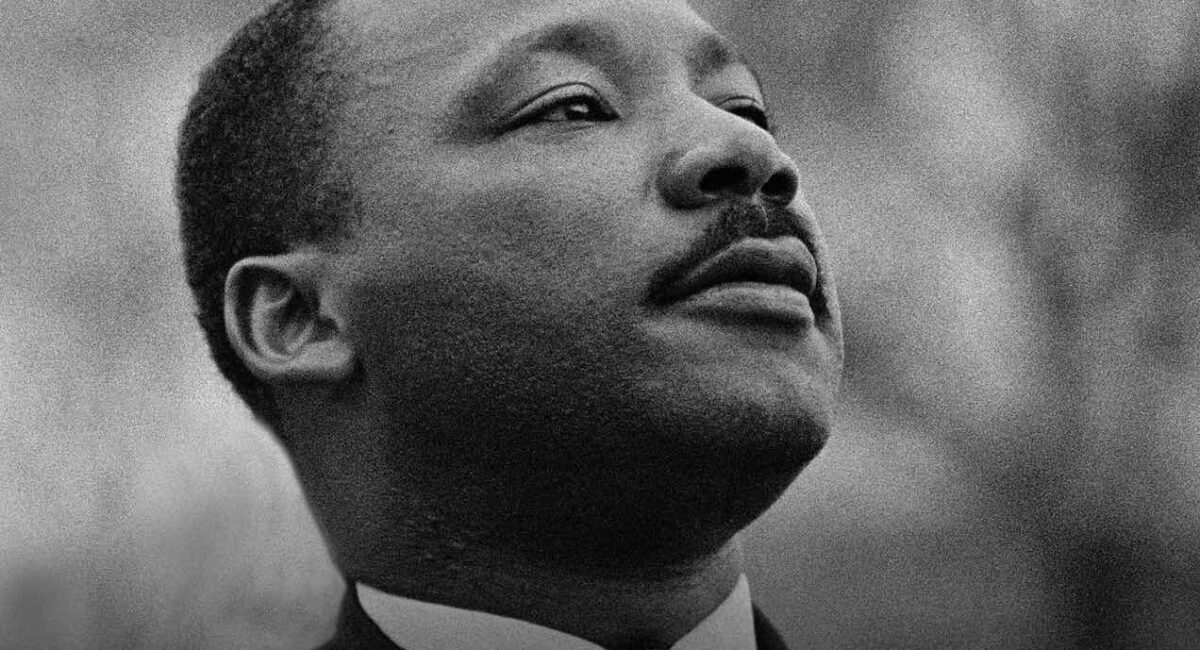

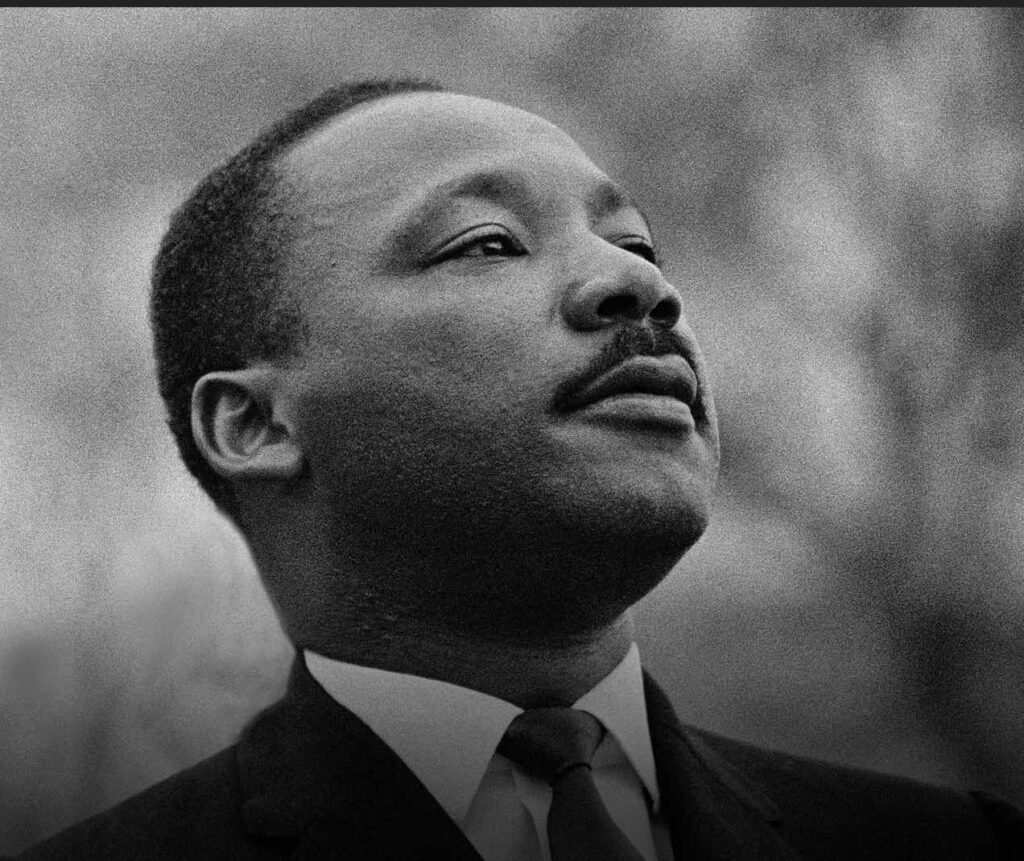

On this Dr. King Sunday, I ask us to spend more time, not just this morning, reflecting on the passage that Geoff read earlier. In the coming days, as you let this sermon reverberate in your heart and mind, reflecting on how intention and impact work in our lives, I ask us to reflect on Dr. King’s words, adapted here for more inclusive language:

It may be true that you can’t legislate integration,

but you can legislate desegregation.

It may be true that morality cannot be legislated,

but behavior can be regulated.

It may be true that the law cannot change the heart,

but it can restrain the heartless.

It may be true that the law can’t make a [person] love me,

but it can restrain [them] from lynching me,

and I think that’s pretty important also.

So while the law may not change the hearts of [people],

it does change the habits of [people].

And when you change the habits of [people],

pretty soon the attitudes and the hearts will be changed.

It is Dr. King Holiday weekend. As such, it is hard for me to imagine going to church and not singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” what is called in African American communities, the Black National anthem. This is hymn with another complicated cultural context in Unitarian Universalist congregations, especially those congregations (of which our congregation is one) where there is not a strong multiracial membership and in particular, a strong African American presence.

There are Black Unitarian Universalist religious professionals, and white ones, who believe that UU congregations should not sing this hymn, because it comes off as white appropriation of a part of Black culture and tradition that is so very sacred. There are Black Unitarian Universalist religious professionals, and white ones, who believe that if sufficient context is provided, it can be done and should be done, as part of the UU commitment to be anti-racist communities. There is no consensus.

I believe that it is possible to provide sufficient context to make singing this sacred song okay within a predominantly white context. I come to this conclusion in part because of my own experience: I learned this song singing it in the pews of my home UU congregation and it helped me to be more literate about Black culture, giving me one tool (among the many I needed) to cultivate relationships with Black community partners in places where I have ministered. In that process, I have learned how very, very important it is that we stand for this song (those of us who can – including those of you watching the livestream) when it is sung -doing so in a way that brings dignity to the hymn.

In not doing so, the impact might be unintended disrespect. And on this Sunday, of all Sundays, that is not the message we want to bring to the world.

To do so, conveys that we understand that this is not just any old hymn,

or even one from within African American culture, but is one that is, like I said before, sacred.

~~~

Let us be, as the words from the late Rev. Orlanda Brugnola, at the top of the order of service say, always newly wise and newly foolish, asking that our mistakes be small and not hurtful, yet willing to reckon with the impact when they are.

Let us be the wise ones who recognize that those who do harm do not always intend to; and that it is still ours to reckon with the impact.

Let us, when someone tells us of a stain on our face or the impact of our actions, let our defensiveness rise and fall internally, choosing our outward response to be one of gratitude and curiosity.

Let us, should we be the one to shake what turns out to be the head of an alien and inadvertently cause the annihilation of a planet, or at perhaps a world of embarrassment, let us come back from that moment to remake an even better world.

Let us be a part of the world that Dr. King dreamed, in which we do not focus just on the hearts of our fellow humans, but also on restraining and transforming the harmful habits – their habits, our habits – that we might come closer to building Beloved Community.