First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

October 8, 2023

In her book, Medicine Stories, Aurora Levins Morales writes:

“Acknowledging our ancestors’ participation in the oppression of others and deciding to balance the accounts on their behalf leads to greater integrity and less shame… It becomes possible to see the choices we make right now as extensions of those inherited ones, and to choose more courageously as a result.”

Now, it may not feel like doing the work of acknowledgment our ancestors’ participation in oppression leads to less shame. Sometimes we can get stuck in shame and stay there for an uncomfortably long time. There is a path forward, there is a path through, and when we have spent much or most of our lives not tending to acknowledging these shadows, that path through can feel like it’s the destination, rather than a temporary part of the journey.

This is why we do this work not alone, but in the mixed companionship of those who inspire us; some who cajole and hold us accountable to each other (which doesn’t always feel good but serves a greater purpose); hopefully many who can hold us as we weep; a trusted few who can hold a loving mirror in our less-than-graceful moments; and a few who make us laugh as we trod, and roll, and move along the stony path.

How we hold history, how we face the truth of it, is a strong indication of how we are doing when it comes to holding the truth of our present day. We see this when it comes to how our nation is doing with its latest transgression of history as some stoke the false controversy called Critical Race Theory. It sure does seem that there is a strong, recurring, insistent impulse towards historical erasure and minimization in the powerful and privileged in this nation. If we are to be true to our principles and values of justice and equity, we must resist whatever quality or quantity of this impulse we find in ourselves.

Here is my big ask for this morning: bring your full attention ~ head and heart ~ to the history I am about to share with you, for we Unitarian Universalists are not immune to that impulse to erase and minimize. Too often we have demonstrated that we prefer to hold the history of heroes, rather than the history of harm. Doing so does not help us build the diverse multi-cultural Beloved Community of which we dream. Doing so does not help us to accountably dismantle oppressions, as our 8th principle guides us to do.

Here are a couple contexts that I want to explicitly name before I go further:

- I am a white woman with no indigenous heritage, about to preach on a particular aspect of Unitarian Universalist heritage in relationship with indigenous communities. I approach this subject with humility, curiosity, and am open to accountability.

- Even in these few months I have been here in Vermont, I can already tell that there are a lot of opinions and feelings and contradictory information about indigenous communities and identity, legitimacy and rightful authority, cultural appropriation and national sovereignty, profit and motivation. This is a live ~ perhaps even electrified ~ topic for our local region. And perhaps, for some of you, a very personal one. As a recent transplant, I feel especially ill-equipped on this topic and will not be speaking to it in this sermon. I approach this subject with humility, curiosity, and am open to accountability.

Heritage is this month’s Soul Matters theme. Just over a week ago, on September 30th, it was National Day of Remembrance, also called Orange Shirt Day, set aside to “honor the children who never returned home and survivors of boarding schools, as well as their families and communities.” Next month, November, is Native American Heritage month. Tomorrow is Indigenous Peoples Day. So, it seems appropriate for us to explore Unitarian Universalist heritage and history as it relates to indigenous communities of this continent.

When we hold our heritage with integrity, we learn the devastating chapter in North American history of Indian residential schools. We learn that Native children were forcibly removed from their families. We learn of schools with the philosophical and pedagogical motto was “kill the Indian, save the man.” We learn that we Unitarians were involved – that it was not just other Christian denominations. Not only did we financially support the systems of these schools, we ran two of our own.

Perhaps you are like me, somewhere between surprised and shocked, to hear that Unitarians had their own Indian residential schools. It is not something I learned as a lay person or in seminary. However, it had been duly, and often proudly, recorded in contemporary materials that Unitarians were involved in the establishment and management of a number of such schools in the 19th century, as well as taught at them, often understanding this as acts of service or social justice.

According to Rev. Dana Stiver,

Early Unitarian writings indicate that many Unitarians propagated, or at least remained complicit in, the popular idea that westward expansion of the American frontier marked an advance of “civilization” over the “savagery” of Native peoples.

Rev. Samuel Atkins Eliot, president of the American Unitarian Association (AUA, the 19th century equivalent of the UUA), wrote this in his thesis at Harvard while preparing to become a Unitarian minister:

Indians as a race are inferior intellectually to white men. But this is not or should not be the object of Indian education to make Indian scholars. … We do not expect now from the Indian any contribution to national thought or character. …Indians must be taught to live properly before they can be taught to think and act with judgment and independence.[1]

When we hold our Unitarian Universalist heritage with integrity, we find that nearly or fully forgotten aspects begin to emerge. In 2007, delegates at General Assembly called for our faith movement to “uncover our links and complicity with the genocide of native peoples.” Out of that came it became more widely known that in 1870-1876, the AUA worked with the Ute Tribe in Colorado under the Grant Peace Policy and did so to “present to them the better phases of a Christian civilization.[2]”

In response to uncovering this aspect of our history, then UUA President William G. Sinkford (our first president of color, which is likely not a coincidence) used the occasion of the 2009 UUA General Assembly to offer a formal apology to the Ute tribe for Unitarians’ historical complicity in crimes and violence against the Ute people. The apology was accepted by a member of the Ute tribe.

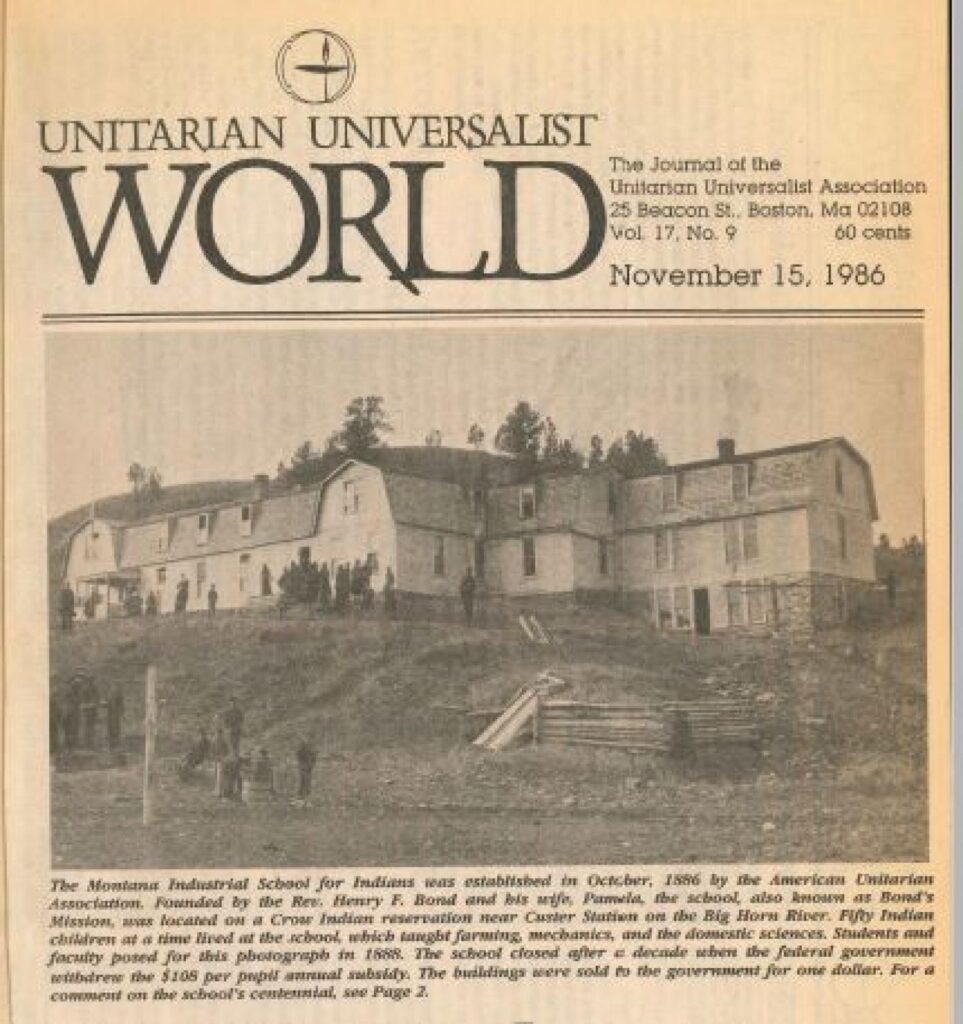

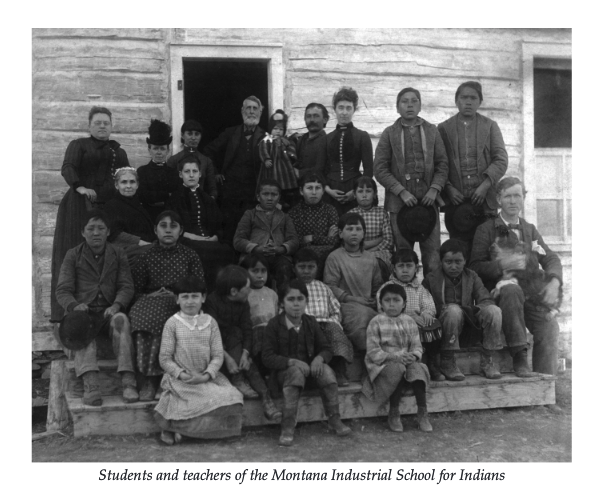

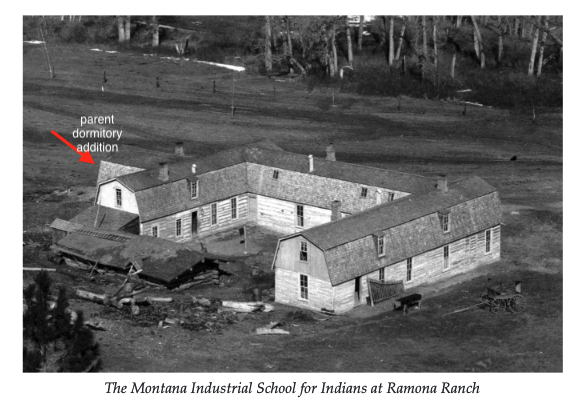

This is not the only residential school we founded. There was also the Montana Industrial School for Indians at Ramona Ranch. It is sometimes referred to as the Bond Mission, so named after Rev. Henry Bond, who founded it with his wife, Pamela. They led it for the first few years that it operated, which was from 1886-1897.

The history of the Montana School, or the Bond Mission, is available to us because of the late Margery Pease, a member of the Crow Nation who was also Unitarian. She published a history on the centennial of the opening of that school. Her book is called The Montana Indian Industrial School: A Worthy Work in a Needy Time. She had a personal connection – her husband’s ancestor was one of the early Crow staff members of the school history.

Margery, who died last year at the age of 96, knew the importance of holding this aspect of UU heritage, inviting and ensuring that others do the same. In 1986, she and her husband organized a centennial commemoration which descendants of students of the school attended, as well as the then president of the UUA, Bill Schultz. His remarks included these remarks:

If Henry and Pamela Bond were with us today, I am confident that they would say to the Crow community, “We who taught your parents and grandparents are now your students.”

I don’t know about you, and with all due respect to my colleague, but Schultz’ remarks strike me as rather saccharine revisionism or flat-out whitewashing, rather than holding our heritage with integrity, so that we might accountably dismantle systems of oppression.

We have access to an even more detailed history of the Montana Industrial School because of an article, published just a few years ago, by Rev. Dana Stivers in the Journal of Unitarian Universalist History. I am deeply indebted to this article, which greatly informs and enhances my understanding of this topic.

In it, I learned how Rev. Bond meticulously tracked the enrollment of the school, as any good administrator should. Also, as any “good” white colonizer intent on assimilation, Rev. Bond noted not just the child’s Crow name, and their father’s name, but he gave each pupil an Anglicized name, by which they would be known going forward.

Though some Crow parents enrolled their parents willingly, there is clear evidence that others were coerced, with food rations withheld, until they brought their child to the school.

Other signs of resistance include some of the children at this school regularly running back home. Including once, when 17 boys all left on the same night. This only began to slow when Rev. Bond listened to one of his newly hired staff, a man whose mother was Crow and father was European. This staff member, George Pease, suggested that they build a dormitory for visiting parents. Once this was completed and families had a means to stay connected for meals or longer visits, the running away ebbed.

This adaptation shows that over time, Rev. Bond was able to learn how to make the school into a less hostile environment, taking into account indigenous views on how to do better. Yet, as Stivers notes in the article:

Despite evidence of good intent and even expressions of love, we must recognize ultimately that the record reveals a painful picture. Crow youth were removed from their homes, at times against their will, as their running away attests. They were made to assimilate to Anglo-American ideals as the Unitarians worked to eliminate Crow language and culture.[3]

I do not want to fall into the too-easy trap of talking about indigenous people as historical artifacts. This is not the case for the United States (despite a violent Manifest Destiny, ongoing attempts at cultural erasure, and the erosion that comes with poverty and displacement). This is not the case for Vermont. And this is not the case for Unitarian Universalism.

You already heard me recognize and give thanks to Unitarian Universalist, and member of the Crow Nation, Margery Pease for surfacing the story of the Bond Mission.

I think of Mike Adams, second-generation UU and member of the Lil’wat people, whose mother was a survivor of an Indian Boarding School in British Columbia. He wrote a powerful Braver/Wiser meditation on placing her ashes to rest after she died.

I think of Indigenous climate activist and Unitarian Universalist Jacob Johns, who was shot on September 28th (less than two weeks ago) while trying to protect others as they protested the attempts to erect a conquistador statue in New Mexico.

I think of my UU indigenous ministerial colleagues, from and with whom I try to learn, in our shared commitment to bring liberatory love, yes to the whole world, and yes, to Unitarian Universalism.

I’m going to save some time closer to the end of the service for thoughts about what to do with this information, how to go through and forward, as well as some thoughts on the purpose and vision for the land acknowledgement we do as part of our Sunday services.

Let us remember.

As we choose to highlight our heroes, let us not keep in the shadows our heritage of harm.

Let us choose more courageously.

Let us not shy away from the fullness of our heritage.

Let us circle ‘round for freedom; let us circle ‘round for release.

Let us practice liberation and love.

So be it. See to it. Amen.

Closing Words

And so here we are. We know what we know and cannot unknow it. What do with do with this this history and heritage?

- Commit to move through any shame that might arise as you learn.

- Read Rev. Stivers’ article on the Montana Industrial School for Indians.

- As an act of accountability and embodiment of our Unitarian Universalist values and principles, write to your Senators and Representative and voice your support for the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the U.S. Act, which the National Native American Boarding School Coalition supports.

Two of the three of those are concrete actions (the first one is a life-long spiritual, emotional, and political commitment) for you as individuals. Here is a question I want to raise to us as a congregation, one without a clear solution.

What do we do with the land acknowledgment that has become a part of our Sunday service welcome? It is a conversation that the Worship Associates and I have been holding, though I recognize the conversation started before I began to contribute.

Not all that long ago, and not only in the UU universe, land acknowledgements became de rigeur, a requirement for any progressive institution to indicate their recognition of the legacy of Settler Colonialism on this continent.

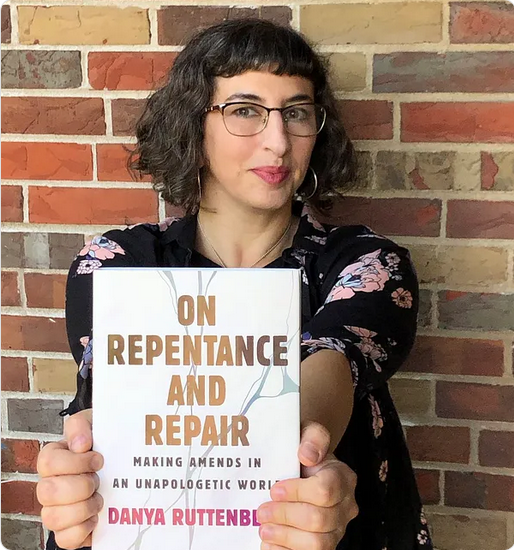

Yet, there has evolved a critique of land acknowledgements as a form of “virtue signaling,” of lip service that makes the congregation feel better about itself, as if acknowledgement is the same as action. (Applying the wisdom from Rabbi Danya’s book, On Repentance & Repair, about which I preached just a few weeks ago, we know this is not enough.)

I mentioned earlier my indigenous colleagues – it is from them I have heard it said that unless there is a commitment beyond a land acknowledgment, then it is just spiritual window dressing and thus, disappointing and sometimes, painful.

It’s such a multi-layered thing, these acknowledgements. I have heard some in the congregation ask why we must say them every Sunday, perhaps even with a tone less than radical curiosity, and more “I’m done with it. Can we be done with it?” Some ask the question out of concern that if we speak the acknowledgement every Sunday, we stop hearing it. And some have expressed concern about the congregation not going deeper.

Add to this, the request to do what is called a “labor acknowledgement,” which is a newer practice beginning to emerge on the American scene. A labor acknowledgement recognizes that our society, its wealth and infrastructure, would not be possible without the forced labor of African American enslaved peoples.

It’s a newer concept, and one worthy of our attention. It’s gotten my attention. It does seem to me that there is more of a commitment to anti-racist efforts at First UU, so that if we were to speak a labor acknowledgment, it wouldn’t be just lip service. First Parish Unitarian Universalist in Canton, Massachusetts, has intentionally chosen to do a combined land and labor acknowledgement.

And then, just to add another layer, there is the practice of acknowledging the ecosystem in which our lives are lived. It’s called a watershed acknowledgement and its purpose is to express our indebtedness to Earth, to this part of the Earth and the natural processes all around us, for this is another relationship where dominion has been the overriding response, and we, as people of faith and conscience, want otherwise.

While speaking any such acknowledgement takes place during worship, and the Senior Minister has ultimate responsibility for the shape and content of our Sunday services, this conversation touches on so many aspects of our shared life, and the vision of who we are and who we want to be, it does not seem to me that this conversation belongs here (me), or only among the Worship Associates. Given the congregation’s adoption of the 8th principle, with our commitment to “to journey[ ] toward spiritual wholeness by working to build a diverse, multicultural Beloved Community by our actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions,” it seems like the more of us who educate ourselves (before we form an opinion) and reflect on this together, the better.

And with these words, these closing words come to a close.

[1] “The Montana Industrial School for Indians at Ramona Ranch, 1886-1897″, Dana Capasso Stivers

[2] 1877 AUA Yearbook

[3] “The Montana Industrial School for Indians at Ramona Ranch, 1886-1897″, Dana Capasso Stivers