The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

October 2, 2022

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

“Remember: we are the promises we make.”

In a letter sent to all congregations with a book, this book, in the summer of 2021, the UUA Commissions on Appraisal wrote those words:

We are the promises we make.

Unlocking the power of covenant, June, 2021

Martin Buber once said that we are “promise-making, promise-keeping, promise-breaking, and promise-renewing” creatures.

Why talk about covenant now?

Because we have been through 2 ½ years of pandemic and aren’t out yet, are about to go through our third pandemic winter and we don’t know what’s in store, even with a new bivalent booster and easier access to antiviral treatment. We have experienced the fraying impact of the pandemic. Covenant can remind us of who we are.

Why covenant now?

Because last February we voted to adopt the 8th Principle and committed ourselves to take it deeper this year, which, if we follow through, will likely result it messy conversations that are necessary for authentic and real spiritual growth. Covenant can help with that.

Why covenant now?

Because this congregation is at a crossroad, on the brink of a serious transition that does not yet have clear shape or form, and covenants – the promises we make to each other about how we will be with each other – can be a reassuring foundation or helpful scaffolding or a just-in-case netting when there is uncertainty, when there are anxieties, when there are people not behaving at their best out of fear or anger or hurt or confusion or stress or grief.

Covenants are powerful tools, especially when congregations are in transition or in conflict. This book names transitions common in congregations, including ours: decline in size.

So, what’s a covenant? Why is it relevant? And if it takes courage to do, as the title of this sermon indicates, why should I want to do it?

We got some answers from the video. I want to go a little deeper. But first, I want to tell you about a place I visited this past summer when Tony and I traveled to England to visit his family.

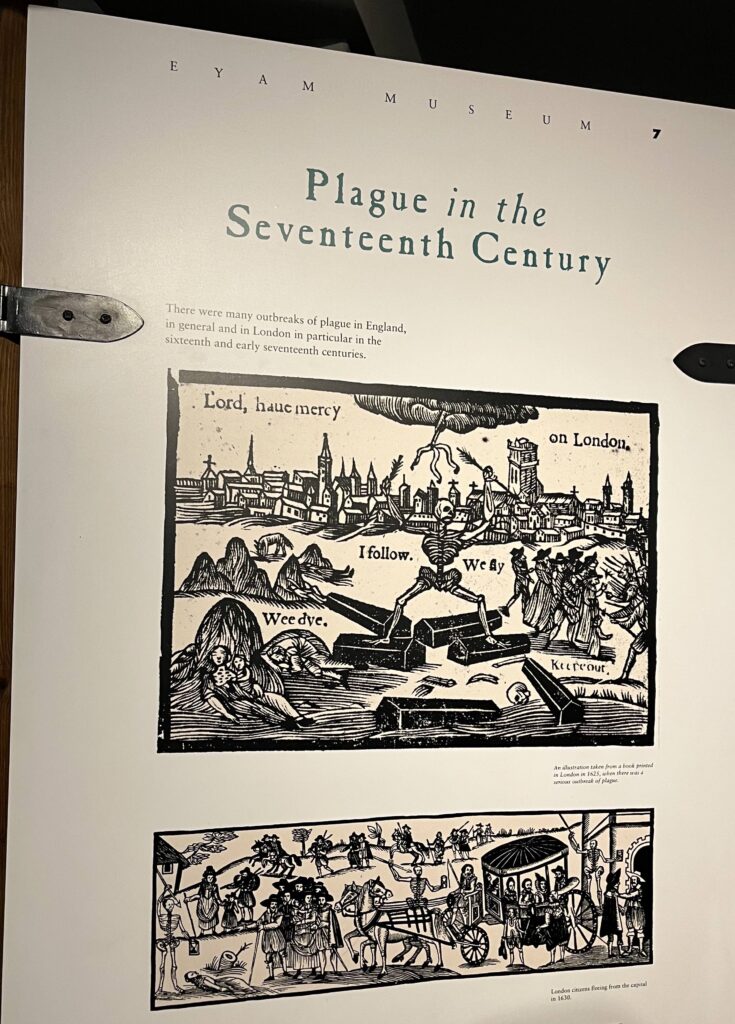

While we were there, we took a side trip to the Peak District, spending an afternoon in the village of Eyam. You see, early in the pandemic, I read Geraldine Brooks’ novel, Year of Wonders, about the village of Eyam and their unique (and valiant) response when the plague struck in 1665 and stuck around for 14 months.

Very soon after the village discovered that they had among them an outbreak of the plague (this was, in fact, the last historical outbreak), they made and abided by a three-point covenant.

First: to stay within the physical bounds of the village. Think: quarantine.

Second: to no longer gather in-person for church. Think: social distance.

Third: bury the dead near where they died (at home), rather than transporting them to the cemetery. Think: limit the contagion (even if at that time, their understanding of how the plague was spread was off).

The stakes were high. The level of sacrifice was deep. The need for everyone to abide was essential.

It was also essential that those with whom the village was in association do their part. Eyam was not self-sustaining. What community is? They could not go it alone. So neighboring villages and the local presiding Duke made sure they had sufficient access to food and supplies to support them in keeping their covenant, to support them in keeping the plague from spreading.

Eyam paid a huge price – a much higher death rate than even in urban London. Of the 800 residents, 260 died in that 14-month period. Yet, by abiding by their three-point covenant, they were successful: they saved countless lives in the neighboring villages and the nearby city of Sheffield.

I want to assure you that when we covenant, the stakes are not quite that high. In this congregational life, you won’t be asked to make the depth of sacrifice the fine folk of Eyam made.

But sometimes, covenants ask us to make sacrifices. To listen when our impulse is to speak. To cede cultural privilege (gender, race, class) so that those historically marginalized might be heard. To pledge more than other people because you can and they can’t. To go along with a majority-voted decision even if it wasn’t your first choice, or even your second. To listen to religious language on a Sunday morning because it meets someone else’s spiritual thirst, even if it makes you feel a little allergic.

These aren’t examples of any explicit covenant we have ~well, curbing the impulse to speak and interrupt actually is ~ but are somewhat implicit promises that Unitarian Universalism asks us to aspire to.

Earlier I said that covenants ask us to make sacrifices, but that’s not quite right. More accurate is that they help us make sacrifices necessary for the common good. They help us keep “we” at the center of our doings, rather than “I”. In fact, that is part of the definition of covenant that the UUA Commission on Appraisal uses in their book:

“A covenant is a mutual sacred promise between individuals or groups, to stay in relationship, care about each other, and work together in good faith. In the Unitarian Universalist tradition, we week to raise the ‘we’ above the ‘I’ – the community above the individual. As seekers, we willingly choose to love each other and stay in relationship over and over, again and again. In this way, although we may break promises, by leaning into the transformational power of our faith, we can begin again in covenant to love.”

Unlocking the Power of Covenant, (p. xiii)

As the video informed us, historical references point to an external authority imposing a covenant – coming from god or a royal. Such covenants are considered vertical – from on high, imposed below. Yet instead of hierarchical covenants, there are horizontal ones.

That’s what we have in Unitarian Universalism. The authority or source of loyalty is not external: it comes from within community. It’s parallel to how we approach the blessing of our homegrown holy water: the blessing is egalitarian and comes from within and among us. And while religious conservatives bind together covenant and creed, religious liberals see these as distinct and separate. This means that as a congregation we can covenant around a shared vision without requiring that we all sign onto the same creed, or belief.

Covenants differ from contracts or treaties. They are closer to promises or commitments. In a contract, if one party breaks it, the contract is broken. That’s not the case with covenants. If one party acts out of covenant, the covenant still holds for others who entered into it. The most skillful covenants contain within them a way back when someone is out of covenant and would like to return. Since we are all promise-making, promise-keeping, promise-breaking, and promise-remaking creatures, it’s good for us to recognize that at some point, in all likelihood, all of us will be out of covenant. All of us will break a promise. Covenants can remind us that we have within us the power to remake promises as well.

~~~

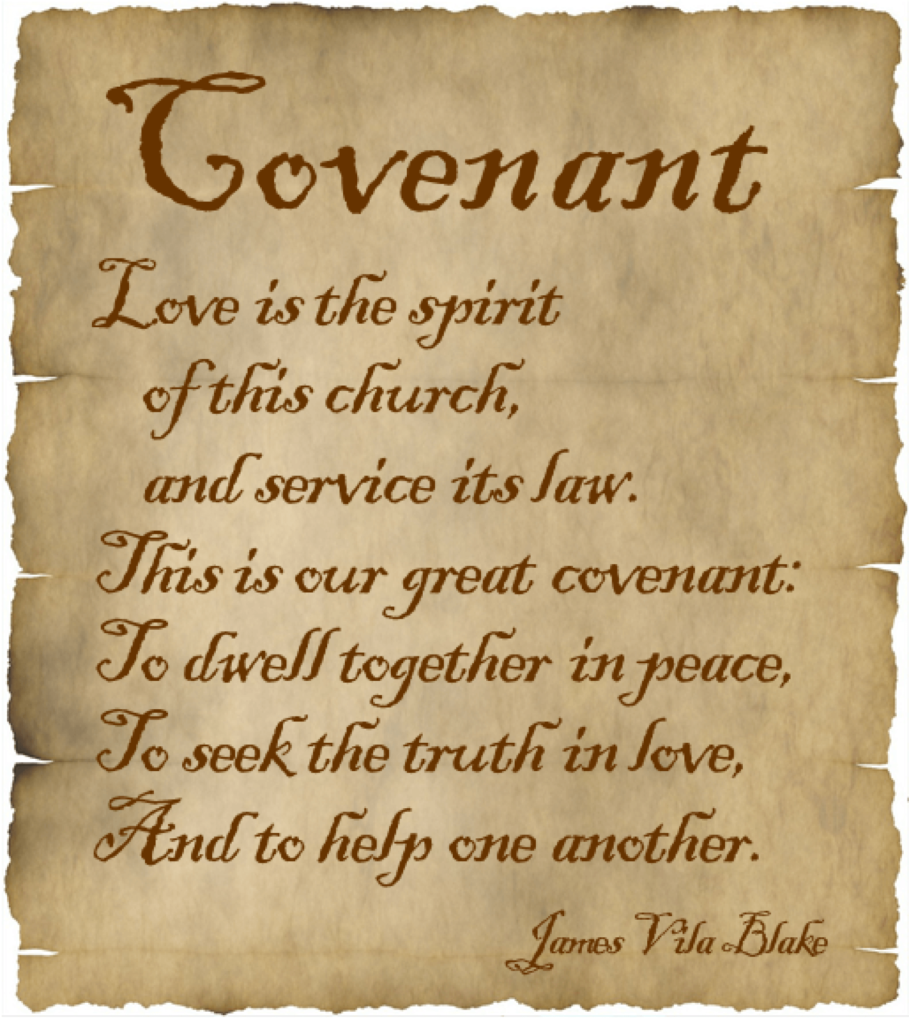

If, while you are traveling, you go visit another Unitarian Universalist worship, a common covenant spoken in unison in many congregations is this, written by Rev. James Vila Blake in the early 20th century:

Is our Bond of Union our congregation’s covenant? Created by this congregation’s founders, sustained each time we speak it together? An interesting possibility. I would say that if TUS were a tapestry, we have several threads of covenants, some of which are dusty in places and in other places have grown stronger from active use.

We have a Right Relations Covenant, which Vicki read earlier. When we had a Committee on Shared Ministry, they had a covenant. The Futures Task Force and the Social Justice Team is in the process of developing their own. It is common that a minister develops covenants with other ministers who have a relationship with the same congregation. So that means that I have covenants with Rev. Susan Rak, the Settled Minister previous to me; with Rev. Allen Wells, who teaches our Buddhist meditation group; and with not-quite-but-on-their-way-to-being-Rev, Alia Shinbrough, who grew up in this congregation and is sponsored by us on their path to ministry.

The board has its own covenant, first developed in 2019 and most recently affirmed last year. I have watched an evolution of the Board’s relationship to covenant. At first, when I suggested that the Board would benefit from its own covenant, the response was “But we already have the Right Relations Covenant!” With education, and the Board’s extending trust to me, they developed their own, deeper, more aspirational covenant.

Yet, it was always the first thing that was ejected from the agenda when the agenda was over-full (which was and is every meeting).

And then there was a small crisis on the Board. Someone quit without seeking to process their concern with the other members of the Board. At first, the Board wasn’t quite sure how to respond to this resignation. Then one Board member turned to the covenant to help frame both the actions behind the resignation and the Board’s response. It really helped clarify things.

After that, the covenant began to be read in each meeting, even when the agenda was overfull. And just this month, at the Board’s retreat, when we were naming some areas of communication that needed our attention, the covenant helped us move beyond individual opinions and comfort zones into a shared, communal understanding of the issues. The covenant is making a difference in helping us get to a better place. I would say the covenant has gotten more relevant the more we engage it.

I have come to see the process of covenanting as a protective and pliable scaffolding that can help when the foundation is a little shaky or is being actively shook or is being repaired or when there are external elements poking at us, trying to tumble us (hey, pandemic, we see you) or when there are internal shifts that require us to reshape ourselves, that require us to create change. I hope that our Time For All Ages game of Jenga got that across.

Reverend Susan Frederick-Gray, current president of our Unitarian Universalist Association, has said this: alongside mission, covenants are an antidote to individualism. In this American society, so saturated with toxic individualism, her words call to me, and call to us.

But perhaps this way is a better way. It’s certainly more poetic, which makes sense, since it comes from the poet, Gwendolyn Brooks:

When we develop covenants and keep them as living, pliable companions that protect our communal life and our aspirations, then we embody this poetic vision offered to us.

Remember: we are the promises we make.

So be it. See to it. Amen.