I cannot in good conscience ignore the bitter for the beautiful.

It stunned me. That sentence. The voice saying it. The interview that held it.

I cannot in good conscience ignore the bitter for the beautiful.

It was early March and I was preparing for my upcoming pilgrimage in the Deep South, a journey of bearing witness to very specific places of lamentation related to the enslavement of human beings and its long, tentacled aftermath of violence: lynchings, voter suppression, mass incarceration. And the vibrant, creative responses of humans in the face of such systemic oppression.

It was early March and I heard Drew Lanham say in his interview with public radio celebrity, Krista Tippett:

I cannot in good conscience ignore the bitter for the beautiful.

Drew Lanham is an ornithologist – one who studies, and in his case, loves, birds – who has written the book The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature and a collection of poetry and meditations called Sparrow Envy: Field Guide to Birds and Lesser Beasts. Here’s a longer quote from Lanham from that interview, a small chance to get to know his brilliance better:

Well, to me, there’s so much that’s simple out there or that appears simple, but that’s really complex. It’s sort of like the sparrow that appears brown from far away and hard to identify, but if you just take the time to get to know that sparrow, then you see all of these hues. You see five, six, seven shades of brown on this bird. And you see little splashes of ochre or yellow or gray, and black and white, and all of these things on this bird that at first glance just appeared to be brown. And so in taking that time to delve into, not just what that bird is, but who that bird is, and to understand to get from some egg in a nest to where it is to grace you with its presence, that it’s taken, for this bird, trials and tribulations and escaping all of these hazards. And so I tend to think about, I try to think about people as much as I can in that way: that each of us has had these struggles from the nest to where we have flown now, and the journeys that we’re on. And so I think that’s important.

“Pathfinding through the Improbable,” Interview with Drew Lanham by Krista Tippett for On Being

The interviewer, who is white, goes on to recognize that some of what Lanham does is ponder “how slavery and the aftermath of slavery created this alienation of people from the land. … that people were once forced into nature, in places that — environments that we now pass through and even take refuge in were once full of pain.”

This too caught my attention, since I was about to travel to places associated with the ravages of slavery (even though, it must be said, we had slavery here, in New Jersey; even though we had here, in East Brunswick, a slave ring operating in 1818 when gradual abolition was already the law). What would I do when I encountered these lands of lamentation, this terrain of torture?

Lanham, as an African American man born and bred in the South, living and teaching there, responds to the interviewer’s question:

when I see these landscapes, I cannot, in honoring what my ancestors endured — in that nest, really — to get me here to where I am, fledged and flying — I cannot in good conscience ignore the bitter for the beautiful.

I do not share Lanham’s racial or geographic ancestry, but I do share what I hope is a similar intention to see reality as it is, with the truth of history recognized for its presence in the present. So as his phrase took up residence in my head ~ bitter for the beautiful ~ it took on a different shape, one I believe to be complementary.

If Lanham cannot ignore the bitter for the beautiful, if he cannot (or will not) only see the beautiful to the exclusion of the bitter, how might I use the beautiful to help sustain me as I encounter the bitter?

Is it possible to use Beauty as a companion that helps us do the needful when it comes to encountering, engaging, and transforming the Bitter? Are there ways for us cultivate Beauty as a way not to turn away from or numb out to the pain of the world or even our own pain, but to take Beauty as a protective, nurturing, sometimes even fierce companion to get us through the hard, the hurt, and the hopelessness, that befalls all of us in different seasons of our lives?

Maybe it’s important at this point to say what I mean by Beauty. I do not mean traditional beauty with its requirement of symmetry and reflection of dominant cultural bias. By Beauty, I mean three things: Nature. Art. Connection.

By Nature, I mean both perceiving and experiencing natural beauty, even at a distance but ideally not mediated by a screen, and getting in touch with that which is alive.

By Art, I mean both an appreciation for art created by others as well as participating in the act of creation, whether it result is Great Art or not.

And by Connection, I mean trusting relationships that honor and expand our comfort zones, as well as ~ and I think this is crucial ~ allow for and foment laughter. Belly-deep, tear-creep, joy-heaped laughter.

~~~

I knew that my pilgrimage would bring me more proximal than I have ever been to the truth of chattel and race-based slavery, and its vicious progeny. I knew it would be important that I not only schedule space to allow full integration of what I was encountering, but that I find balance and replenishment. I did it with intentionally seeking Beauty.

Actually, I was borrowing a page from a book written over and over again by communities that have experienced systemic oppression ~ from women who experience misogynistic violence and ongoing institutional efforts to control our bodies; to communities of color where racist violence takes overt and subtle forms; to folx who identify as trans or queer, experiencing hostility, humiliation, and too-often fatal harm.

Here’s former U.S. Poet Laureate, Elizabeth Alexander, describing the African American tradition of responding to oppression with art:

Black creativity emerges from long lines of innovative responses to the death and violence that plague our communities. “Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief,” Toni Morrison wrote in “Beloved,” and I am interested in creative emergences from that ineluctable fact.

from “The Trayvon Generation,” by Elizabeth Alexander, The New Yorker, June 15, 2020

Here are three examples from my trip of how I applied this wisdom:

ART. Alongside visiting the Whitney Plantation, one of the few plantation museums set up to tell as accurately as possible the reality of those enslaved, I spent the morning at the amazing ~ AMAZING ~ sculpture garden attached to the New Orleans Museum of Art.

NATURE. After visiting the communities that commemorate the brutal lynching of Emmet Till, both the Intrepid Museum in Glendora and the Interpretive Museum in Sumner, as well as the spot where his mutilated body washed ashore along the Tallahatchie River, I went to the biggest natural bridge East of the Rockies – in Winston County, Alabama. It’s made of sandstone than has been worn away and it towers far overhead, like a swiss-cheese cave.

This was especially necessary as the poverty in that part of the Mississippi Delta is stunning – there were times I struggled to gain sufficient breath, and I have seen many kinds of poverty domestically and internationally, have served folks experiencing urban poverty. This poverty rattled my sternum and stuck at my breath.

CONNECTION. In Selma, Alabama, another deeply impoverished community, I befriended an African American woman visiting from Maryland, who had just dropped her kid off on a college tour an hour away. While she had time on her hands, she thought she would walk the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the site of 1965’s Bloody Sunday, giving respect to those who were beaten by Sherriff Jim Clark and his posse as they demanded voting rights. As I sometimes do for strangers, I offered to take her picture with her own phone – selfies don’t really work in that setting. We spent a sweet ten minutes with her striking poses, some laughter, definitely delight, and an unexpected joyful hug good-bye.

~~~

Beauty. Three different kinds. All crucial, at least for me, to encounter the Bitter and not be consumed by it and not to turn away from it. It’s as if it is an antidote. Beauty as an antidote to the Bitter.

Has Beauty worked that way in your life? Helping you get through bitter times, painful times, time of lamentation? Has Nature been your solace? Has Art or the creation of Art been a source of meaning when you could not otherwise find your purpose? Has Connection been your way through when there was no other way?

Might they be?

In Buddhism, there are the three poisons: greed, hatred, and ignorance. Each poison has an antidote. For greed, it is generosity. For hatred, it is loving-kindness. For ignorance, it is wisdom.

Is Beauty antidote for Bitter? I don’t know. But maybe. Could be. Worth giving a try.

Because part of how we get to a more just, more equitable reality is if we, especially those of us with identities of privilege, be they economic or racial or gender, if we find our way to encounter, engage, and ultimately transform the Bitters of systemic oppressions.

With that in mind, it is worth saying explicitly that Beauty can-most-definitely not be anesthesia or distraction or opiate. We cannot use Beauty as an escape from what is ours to do in this aching world. At least, not in the long run.

Beauty as a means towards engagement, not path away from it.

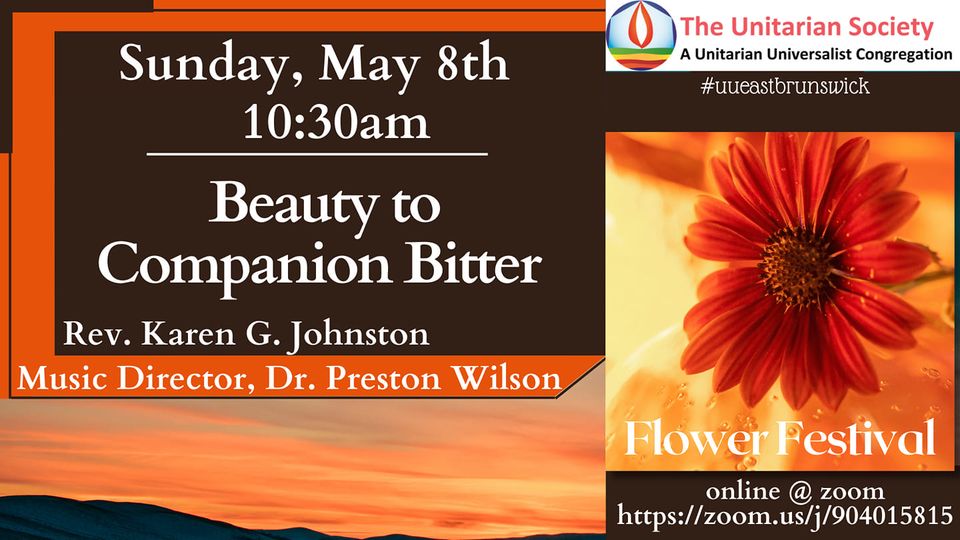

May the flower you take home with you today, symbol of the beauty and the inherent worthiness of someone else in this room, symbol of your own beauty and your own inherent worthiness, symbol of our collective, diverse beauty, may this flower be a good companion, transitory as it is, to you.

May Beauty, in whatever form that feeds your spirit, strengthens your heart, encourages your courage, be companion to you. Companion in your own hard times. Companion when you are living into those values that call us all to find the work that is ours to co-create collective liberation.

So be it. See to it. Amen.