The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

March 20, 2022

Apocryphal. It was only when I was in seminary that I learned the word, “apocryphal.” It means something that is made up – a legend that might be true, but perhaps not fact-based.

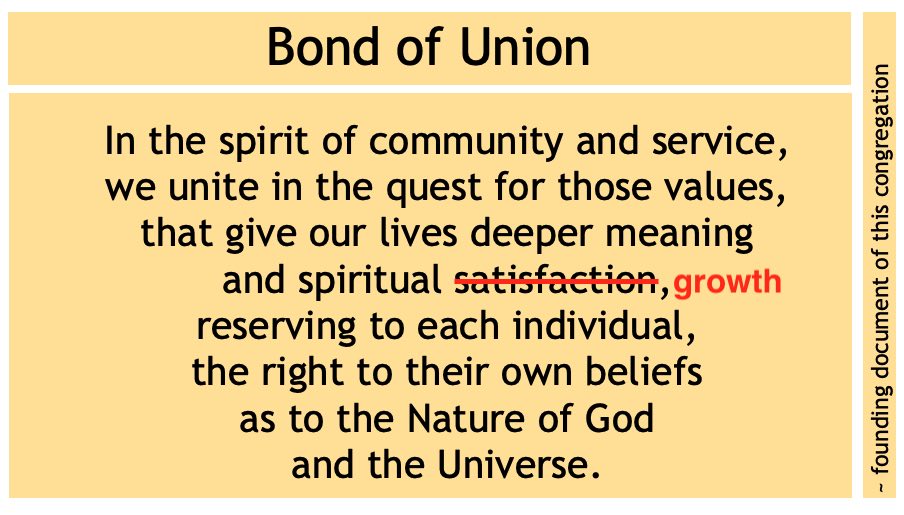

Here is the apocryphal story I tell myself nearly every Sunday – whenever I hear the congregation recite the Bond of Union. I tell this story silently to myself – a story that is completely made up and based on nothing other than my speculative imagination. I tell it silently to myself each time I am faced with the decision whether to speak the phrase “spiritual satisfaction” as it is in the text of the Bond of Union, for this phrase is grating to my soul and goes against so much that I believe. And, from my perspective, it goes against much of what our Unitarian Universalism signals and symbolizes.

Spiritual satisfaction? Is that all this community aspires to? That is such a low bar. How did this come to be? Why is it still so?

Here is the story my mind tells of how it came to be:

In the early 1950s, the religious landscape of these United States looked significantly different than it does now. Secular forces did not yet have the hold that it has now. While there was religious diversity, it was far more hidden. Christianity exercised even more hegemonic influence. Far more people participated in religious congregational activity, typically the religious community into which they were born. Conformity held far more sway than spiritual seeking or the right of individual conscience.

Yet there were always misfits, heretics, and outliers. There were always atheists and non-theists, hidden within such communities, or existing outside them. There were always people who understood that no single religion has the monopoly on capital-T truth. There were always people very much like ourselves.

This was true of a group of people who lived in the greater New Brunswick area. They attended Sunday services at First Unitarian in Plainfield. In the early 1950s, the American Unitarian Association (AUA – this was before the merger with Universalism) oversaw a concerted effort to found new congregations in communities near universities. This group raised its collective hand. They gathered together their time, talent, and treasure, and as part of the wider Unitarian Fellowship Movement, they founded this congregation. For nearly a decade they met in rented spaces: holding Sunday services, calling their first minister, teaching their children, and eventually purchasing property and erecting this building.

Imagine these people – some of you long-timers actually knew some of these people – and how they existed in a society that required more religious dogmatism than they could stomach. Imagine the social pressure to “go to church” (even for the Jews). Imagine what it was like to raise children, feeling isolated and concerned about religious influences not of their choosing. Back then, there was no internet that allowed someone to find “like-minded” people. There was out and out discrimination against those who proclaimed their atheism or their doubt about the existence of god.

I can imagine how, give all that, when founding a new congregation that welcomed its members to establish their own understanding about the nature of god and the universe, the unrealized goal of spiritual satisfaction, so long outside their grasp, made perfect sense.

THAT is the apocryphal story I tell myself to help me understand why the founders of this congregation chose that phrase. It helps me have compassion towards what is now a problematic term.

I have wondered if this phrase or attitude – spiritual satisfaction – is something we might find in other congregations that were founded during the Fellowship Movement. I reached out to my colleagues who serve congregations founded in this era (considered 1948 -1967), yet none who responded have such a phrase in the founding documents of the congregations they serve. It’s possible that there are other congregations saddled with this phrase, but if so, it’s not something that was widely present enough to call it part of Fellowship culture.

We will likely never know what was on the minds of the founders when they chose that phrase. We will likely never know if there was even a debate about it. Ultimately, while an interesting thing to know, I am much more curious about that second question that I posed: why is it still here?

The text of the Bond of Union that we recite each Sunday is not the original. It has been revised at least twice: once to remove words like “mankind” and “he.” The more recent change was either 2017 or 2018, when the board tasked a small team to review and recommend revisions, away from gender binary language.

I praise the impulse, twice over, to greater inclusivity and lesser exclusion. This is, indeed, one of the strongest impulses within Unitarian Universalism. I am thankful to not have to face the choice of binary language ~ we used to say “the right to his or her own beliefs” ~ knowing it would erase some of the very people in the room.

~~~

Reverend Tony Larsen wrote a sermon titled, “Why You Should Not be a Unitarian Universalist.” There was an unusual amount of tongue in cheek in that sermon. Here are his words – it’s the last in his list that I am hoping to draw your attention to:

My friends, not everyone can be a Unitarian Universalist. Not everyone should be a Unitarian Universalist. Because the first criterion for getting into this church is: you’ve got to know how to sin. That’s very important to us; and not everyone knows how to do it. We don’t want people here who never do wicked things. We don’t want people here who are holier than thee or thou. We don’t want people who have made it in the salvation department and are just waiting around to get picked up. Because people with too much heaven in them are hell to live with.

https://urbigenous.net/library/why_not_unitarian.html

We don’t want people who have made it in the salvation department and are just waiting around to get picked up.

Reverend Tony Larsen

That sounds to me not necessarily like hell, but what our Bond of Union says is this congregation’s aspiration. People who aspire to make it and having done so ~ having attained satisfaction ~ then just wait around.

At the time of our last review of the Bond of Union, I encouraged that small group to broaden their review and to consider what it means to keep that phrase “spiritual satisfaction.” At that time, the task force declined to take on that task.

I am still very much stuck on this “spiritual satisfaction” thing. Yes: why was that ever okay? But more to the point: why is it okay now? How does it come to be that we, as a congregation, are satisfied with satisfaction?

Satisfaction is not a part of Unitarian Universalism.

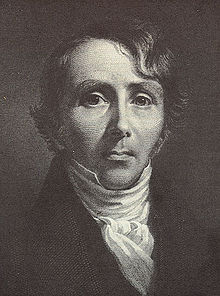

William Ellery Channing is considered the father of Unitarianism because of his so-called “Baltimore Sermon” in which he encouraged us to claim “Unitarian” as a point of pride, even as Trinitarian Christians were calling us heretics, using it as a slur. In that same sermon, he wrote,

“Every mind was made for growth, for knowledge and its nature is sinned against when it is doomed to ignorance.”

William Ellery Channing

Reverend Doug Taylor, who serves our congregation in Binghamton, New York, says of this line that Channing “was declaring that to be our precious inheritance as human beings. It is not sin that we inherit, but our capacity to grow and become closer to God in our goodness.”

In this context, I understand our aspiration towards growth ~ be it spiritual, intellectual, emotional ~ is part of our turning away from the inherent damnation of Calvin and of our Puritan heritage and moving towards our inherent worth. In this context, I understand this affirmation of our nature to grow as the bridge that eventually led our faith into the love of Nature (capital N) as Transcendentalism emerged from within some of our ranks. Which, in modern times, we can connect with our 7th Principle affirming the interdependent web of all of existence of which we are a part.

Speaking of our Principles… when we look at the Sources of Unitarian Universalism, as well as our eight Principles, we see no spiritual satisfaction; we see only spiritual growth:

- our first Source is “direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder…which moves us…”.

- the 3rd Principle explicitly includes “encouragement to spiritual growth”

- the 8th Principle includes “journeying toward spiritual wholeness.”

There are at least two ways to conceptualize spiritual growth, maybe more. For my purpose, I think about it on the individual level and I think about it on the congregational level. This sermon is inviting you, on the individual level, to think about your commitment to spiritual growth, or your satisfaction with spiritual satisfaction. What do you want for you?

In May, probably on the same day as our Annual Meeting, I’ll preach about spiritual growth as it applies on the congregational level, where we can think about spiritual growth and four other kinds of congregational growth.

But for now, when I ask whether you might choose spiritual growth over spiritual satisfaction, what I mean is choosing to be alive with curiosity.

I mean spiritual growth as a practice of humility, and even at times, of surrender.

I mean spiritual growth that does not have any laurels upon which we sit, that has a sense of motion and movement, that welcomes the examined life and desires not just to honor someone else’s theological perspective, but to learn from it.

I mean spiritual growth as a willingness to hear the truth of others and be moved by it, even if it does not match our own lived truth (this is especially important for those of us with privileged identities, be they race- or class- or gender-based), so that we might accountably dismantle systems of oppression in ourselves and in our institutions.

~~~

Does it matter whether we stay satisfied with satisfaction or shift, in attitude or text, to spiritual growth? Aren’t these just words that we recite on Sunday morning and discard for the rest of our week?

Just yesterday, I met with a now-young adult once-child of the congregation and with her fiancé, as we imagined their wedding ceremony together. It’s one of the distinct honors, and pleasures, to have the chance to officiate rites of passage for folks connected to the congregation.

As we sat together in my office, before we began talking, I asked Dana to light the chalice. She enthusiastically accepted my invitation to do the lighting. As I handed the box of matches to her, I was expecting her to strike the match, light the flame, and be done.

Instead, as she lit the chalice, she recited the Bond of Union. By heart. Proudly. Clearly. Sweetly. Strongly. As part of her heritage. As part of her identity. As part of who she understands herself to be.

These words – the ones we recite every week – matter. These words say something about who we are and who we hope to be. These words say something about who we are to first-time visitors. These words say something to our children, who are listening, and learning, and keeping them in their hearts, even when they grow up. These words say something to us, about us.

Since that is the case, I ask again: are you satisfied with satisfaction?

So be it. See to it. Amen.