The Unitarian Society – East Brunswick, NJ

January 30, 2022

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

What makes a good life?

While we changed and grew during the pandemic, and there were good things that came out of it, I am guessing that pandemic is not top on our list. It just does not roll off the tongue to say that this pandemic contributes to making a good life.

Pandemic or not, for those of us who are philosophically and/or spiritually inclined, it’s a solid, compelling question. It might even be THE question of all questions. Yet it is a two-sided question, for on the other side, equally as compelling, equally as solid is this question:

What makes a good death?

It is these two questions, one about life and one about death, that were the heart of a recent session of Date with Death Club, the year-long monthly gathering that “explores mortality in community” that I am leading twice this year – once monthly online for UUs from all over and once monthly at the East Brunswick Public library. (It is also being piloted in five other UU congregations this year.)

In December, 2021, in both sessions that I facilitate, we explored the connection between a good death and a good life, recognizing that some of the same systemic barriers to a good life – aka white supremacy culture bred into our legal, medical, and cultural institutions – create barriers to accessing a good death.

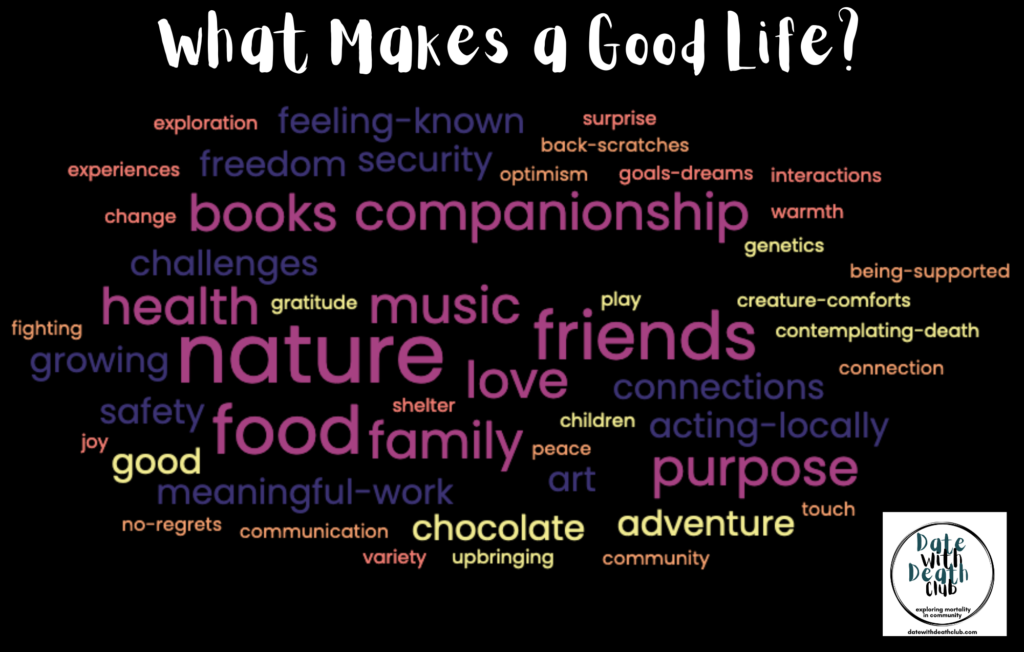

One of the activities was asking small groups to create a list of what makes a good life. The graphic word cloud that you saw earlier in the service from these two sessions. I’ll show it again.

Word clouds communicate collective values. The size of the word indicates the frequency of the response. The larger it appears, the more frequent it was offered as a response. Word clouds don’t just include the most frequent responses. As you can see, there are many words, all the same small size. These are the single responses. So, word clouds reflect entire texture of collective responses.

We can see that “nature” was chosen most often as necessary for a good life. The musts ~ not the wants, but the musts ~ of a good life. Not far behind are friends and companionship (which are very much related), as well as food, family, purpose, books, music, and health.

Noticing what IS here, it’s good to notice what is NOT here. For instance, I was surprised that “love” did not emerge more frequently as a response.

For instance, money. Completely absent from the list. Is that an indication of folks without a materialist bent? A clue pointing to an absolute truth? Or that the folks who gave these answers are resourced enough to not have money as a constant worry? The word cloud offers only a limited view.

This morning, we are going to get a chance to answer the same question: what makes a good life? That is why you have been encouraged to have a second device nearby so you can participate, in real time, in creating our own word cloud. Not quite yet. First, let’s dive a little deeper into the double-faced question.

In the 15th century, not long after the horrors of the Black Death, and still in the midst of subsequent social upheavals, two texts emerged in Europe. Written in Latin, Ars Moriendi were instruction manuals for Christians. Instruction in what, you might ask? The art or practice of how to die a good death.

Ars Moriendi is seeped in the archaic religious and historical tradition of its time, full to the hilt with direction on how to repent of mortal sins and cultivate assurance of ascension to heaven. And yet…I love the implication that death is not solely some biological process. I love the implication that we can practice at death. AND can do so by living a good life.

I experience a kind of envy, or perhaps just a longing, for something like a written manual, something to guide people ~ frankly, to guide me ~ in this worthy quest to live a good life in service of a good death. Or vice versa: to cultivate the possibility of a good death by intentionally choosing to live a good life.

Caitlyn Doughty, licensed mortician, author, and founder of the Order of the Good Death, is responsible, in large part, for popularizing the modern Death Positive movement. Her books, video blog called, Ask a Mortician, and other efforts collectively constitute a kind of modern day art-of-living-and-dying manual. In her book, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory, she notes

For me, the good death includes being prepared to die, with my affairs in order, the good and bad messages delivered that need delivering. The good death means dying while I still have my mind sharp and aware; it also means dying without having to endure large amounts of suffering and pain. The good death means accepting death as inevitable, and not fighting it when the time comes.

Caitlyn Doughty, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes

You see, it’s not easy to separate the questions, or the answers, from each other. To ask what makes a good life leads to reflection upon what makes a good death and what makes a good death leads, inevitable, to what makes a good life.

One of the Date with Death Club participants suggested that one ingredient of a good life was having no regrets. While I am not sure that this would have topped my list, my mind keeps returning to it. Our Soul Matters theme for this month is Living with Intention, which feels to me, related to the double question of a good life/death, as well as the aspiration to live without regret.

I must say, I think it’s dangerous if we get too attached to the idea of having no regrets, if this is a “must” when it comes to living a good life (or a good death). I say this because attachment to, or clinging to the notion of, no regret sounds very similar, at least for me, to the yearning for security, for the longing that there be certainty, for the clinging to perfection, and if not perfection, then things not being messy or clumsy. Things are bound to be messy. We are all bound to be clumsy. We will always find ourselves in the midst of uncertainty.

And I would say that a desire for no regrets is misguided. That instead of hoping or wishing for no regrets, that we must find our way to befriending our regrets, to companioning them, to looking to our regrets as possible teachers. For if we regret something, somewhere within the toss and texture of regret, we just might discern some of our deepest values.

We just might find that if we regret having lied to someone, perhaps even to have protected them from some harshness, that one of our musts to live a good life, and to approach a good death, would be something like honesty, or frankness, or the flat-out truth.

We just might find that if we regret having told the truth and seen the hurt that came, one of our musts might be the exact opposite: that protection from hurt is the must.

I recently read a poem by John Roedel who writes in the form of his conversations with god. In this particular poem John is stuck in a room of his past mistakes. Have you ever felt like you are stuck in a room of your past mistakes? Doesn’t this just sound terrorizing?

In the poem, god persistently encourages John to seek not god’s forgiveness, but John’s own self forgiveness, in order to find the way out. To make a practice of self-forgiveness, saying it over and over, writing in pieces of paper to carry in pockets, writing it on bathroom mirrors, on walls, even on wrists. It is the repetition and the persistence the create the practice that builds the doorway. The doorway out of the room of past mistakes – and into the possibility of no regrets.

There is something wild and beautiful about such instruction: to flood one’s surroundings with messages of forgiveness, so much so, they cannot be ignored or denied. To write it on one’s body, to subvert the intellect, and enlist the visceral wisdom embodied there. To shake one’s rigid foundations with the sheer repetition. Messages of forgiveness. Messages of gentleness. Messages of love.

My colleague, Reverend Seth Carrier-Ladd asks if we can choose to be gentle, rather than judgmental? I think his question is made of the same stuff as John Roedel’s god’s instructions. And ultimately, the same instructions in our reading today from Anne Lamott, beseeching us to “respond with a show of force equal to the violence and tragedies, with love force. Mercy force. Un-negotiated compassion force.”

Choosing to be gentle is not the same as being soft, or lazy, or passive. We still have the responsibility – and I will use an even stronger word: obligation – to do all that we can, when we can, where we can, as we can. To be a faith that truly does place more value in deeds than creeds. If there were a Unitarian Universalist manual for the art of living a good life and possibly dying a good death, I’m thinking there would be a section just on that.

We still have an obligation to do what is ours to do, individually and collectively, to accountably dismantle systems of oppression. And to do it gently, for it will be messy. And to do it with love, for that is, indeed, what makes a good life, not just for ourselves, but for others.

I want to share one final gem with you. Alua Arthur is an African American end-of-life doula, what is sometimes a death doula. Her company is called Going with Grace. In 2020, she gave a presentation at a conference sponsored by a organization called EndWell.

Ms. Arthur has what she calls her foundational question, what we might call a “must” question that is an elegant variation on the one we have been considering this morning. Her version even seems to integrate the point of having no regrets. I want to leave it with you, to be your company in the coming days, weeks, months:

What must I do to be at peace with myself so that I may live presently and die gracefully?

I’ll say it again, this time as a query:

What must I do to be at peace with myself so that I may live presently and die gracefully?

I’ll say it again, this time as a final blessing:

What must I do to be at peace with myself so that I may live presently and die gracefully?

So be it. See to it. Amen.