The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick NJ

September 26, 2021

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

Part I

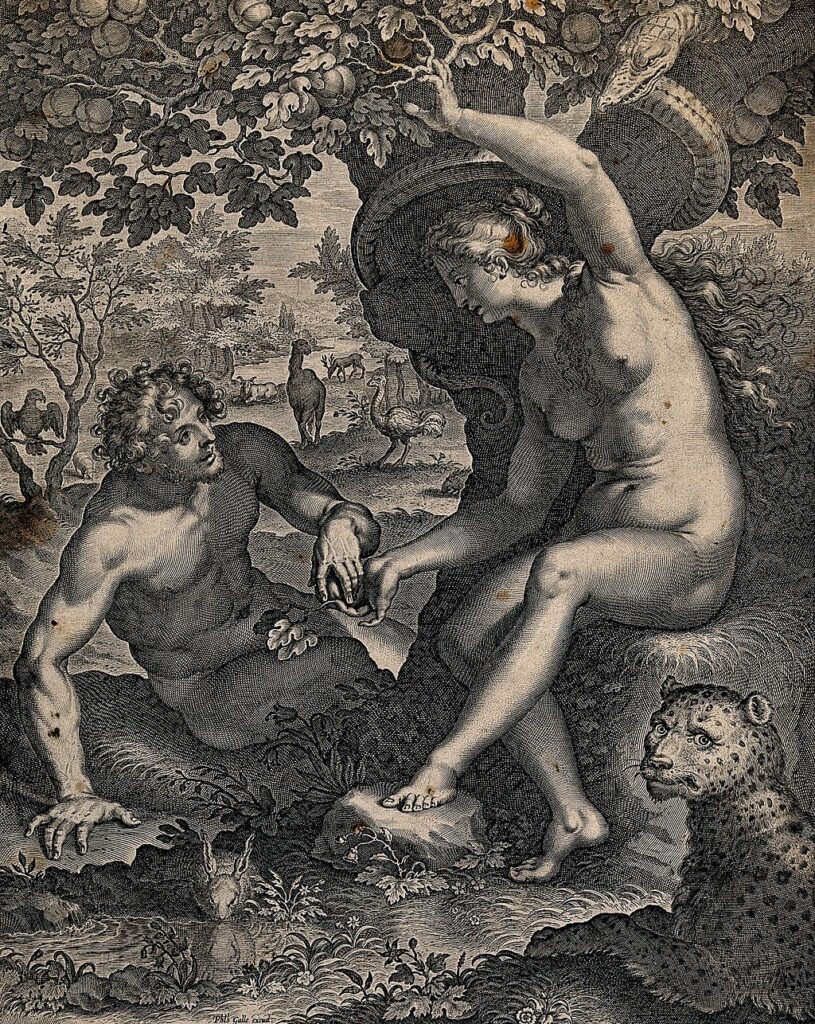

The story of the Garden of Eden, of Adam and Eve: abbreviated. God makes Adam from mud and breath. God makes all the creatures and places Adam as their head. God notices Adam is lonely and creates another person who eventually is named Eve ~ or Chava, or Hawwa ~ “mother of all the living.” (Genesis 3:20). In-between, God tells Adam to eat anything/everything he wants in the garden. Except from the Tree of Knowledge.

Let me ask you: how many parents do you know who forbid their children from something by placing it in their immediate grasp and then walking away?

To the surprise of no one, they break the rule. First Eve eats a fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Adam is with her when she does this, and when she offers it to him, he eats it. When God learns of this transgression, both Adam and Eve pass the blame: Adam blames Eve and Eve blames the serpent. God curses all three and sends them from the garden.

For those who were raised Christian, this story is offered as the explanation for the concept of Original Sin. Yet, this passage pre-dates Jesus by a long while. Before it was a Christian story, it was a Jewish story and there is no concept of Original Sin in Judaism. In fact, at the time of Jesus, there was no concept of Original Sin – it came from a 2nd century Bishop in the new church and was later expanded by others, becoming an entrenched, and quite damaging, piece of dogma.

Whom does that particular interpretation or narrative serve? A particularly patriarchal, hierarchical form of Christianity for one. Whom does it not serve? I would say it serves no women ~ never has, likely never will.

This need not be the only way to understand the story of Eve. This need not be the only narrative. It is, in fact, not the only narrative.

In Judaism, there is a long-existing tradition among rabbis to create midrash – stories that fill in gaps, or attempt to smooth contradictions, in scriptural text. Because there are a lot of them. The midrashic tradition is so embedded that sometimes these stories can be confused for actually being in the Bible.

During the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, Jewish feminists claimed the power of midrash, refusing to let it be the sole domain of the mostly male Rabbinate. They developed a splendid tradition of stories to reclaim what was otherwise used against women and against women’s collective inherent worth and dignity.

For instance, Judith Plaskow wrote what became a well-known feminist midrash about Adam’s first partner – and it wasn’t Eve. Before Eve, according to some ancient midrash traditions (written by men), there was Lilith – not named in Genesis, but read between the lines and into the text. Those ancient midrashim tell us that Lilith refused to be subservient to Adam and fled the Garden. It was her refusal to be subservient and to put up with inequality, that led her to flee, which led to her becoming a demon. Or so the ancient story goes. Judith Plaskow’s midrash of nearly fifty years ago tells of a different Lilith – one who maintains her autonomy and eventually forms a sisterhood of mutual aid with Eve.

***

Whether we believe them or not, whether we take them as fact or myth, creation stories are where we root our collective sense of identity. They provide the foundation for our orientation for the world…at least partially. It is inevitable that we are shaped by them, for their influence is at the collective subconscious level.

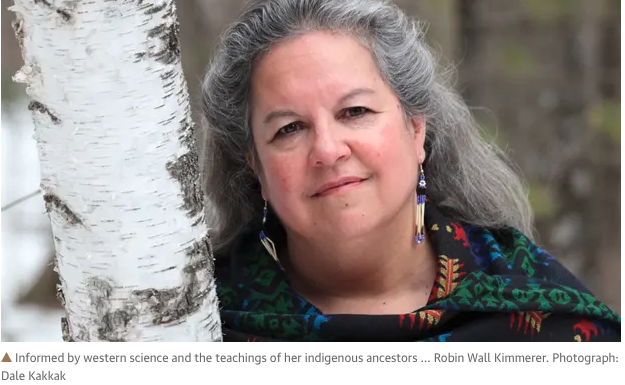

In reflecting on the difference between the story of Eve and the story of Skywoman, Potawatami author, Robin Wall Kimmerer tells us in her book, Braiding Sweetgrass,

“On one side of the world were people whose relationship with the living world was shaped by Skywoman, who created a garden for the well-being of all. On the other side was another woman with a garden and a tree. But for tasting its fruit, she was banished from the garden and the gates clanged shut behind her. That mother of men was made to wander in the wilderness and earn her bread by the sweat of her brow, not by filling her mouth with the sweet juicy fruits that bend the branches low. In order to eat, she was instructed to subdue the wilderness into which she was cast.

One story leads to the generous embrace of the living world, the other to banishment. One woman is our ancestral gardener, a co-creator of the good green world that would be the home of her descendants. The other was an exile, just passing through an alien world on a rough road to her real home in heaven.

…

Kimmerer continues

Look at the legacy of poor Eve’s exile from Eden: the land shows the bruises of an abusive relationship. … we can’t meaningfully proceed with healing, with restoration, without “re-story-ation.[1]” …But who will tell them?”

Restoration.

Re-story-ation.

Yes, who will tell the story of Eve? Will we let the clumsy, often malicious interpreters of ancient scripture, the ones over-saturated with patriarchy and drive to dominate, be the arbiters of this widely influential story? What do we lose if we cede that power to those people, deciding that the stories of ancient scripture aren’t worth our time or energy?

I tell you what we get: pervasive abuse of women. So, pervasive, women blame ourselves for nearly everything, forming ourselves into the shape of shame.

We get deep patterns of physical, psychological, and emotional abuse in every culture and tradition.

We get laws like the one in Texas – S.B. 8 – that places a $10,000 bounty on the heads of pregnant women who dare access medical care, levied by men in service to the power of patriarchy.

We get “missing white woman syndrome” where mainstream media pays disproportionate attention to missing white women than to missing Indigenous women and other women of color.

We get any woman-identified body demeaned, subjected to systemic violence and pervasive threat of violence.

We get a world in which a binary sense of masculine and feminine cuts every human in one way or another, silencing parts of us, maiming soul, stunting psyche, sometimes killing us.

What might we gain if we do not cede that power and authority? What if we were to choose the freedom that comes from accepting responsibility for our own destinies, our own trees of knowledge? Kimmerer challenges us with this question:

“How can we translate from the stories at the world’s beginning to this hour so much closer to its end?”

What if we were to reclaim Eve as ancestor and kin, shero and inspiration? Might we lose the false and terrible calm promised to only some of us? Might we be able to emerge from boxes imposed on us, entrapping us?

In the second half of this sermon, I’ll try to tackle that question.

Part II

Instead of Original Sin, how might we understand the story of Eve? How might we understand her decision to eat the fruit as something not sinful, but not even a mistake? Where can we turn to different understanding, empowering interpretations, that help us not wed ourselves to the past, but give us inspiration for now and into the future?

In juicy, meaningful situations like this one, the first place I tend to look is poetry. Poetry long before scripture. Poetry as scripture. Perhaps this is one of the tell-tale signs that I am a Unitarian Universalist? Could be. So, let me share with you these delightful passages from poets who have claimed the story of Eve as their own, remaking it for all of us, an invitation to shift not only the narrative of Eve, but of our own lives.

First, there is our reading today. Titled, “Eve, After,” written by Danusha Laméris, published in 2013. Let me share with you again the ending:

Foolishness, betrayal,

—call it what you will. What a relief

to feel the weight

fall into her palm. And after,

not to pretend anymore

that the terrible calm

was Paradise.

In that piece, you can hear the echoes of this earlier poem, written by former U.S. Poet Laureate, Rita Dove, called, “I Have Been a Stranger in a Strange Land.” It ends in this way:

And there was no voice in her head,

no whispered intelligence lurking

in the leaves—just an ache that grew

until she knew she’d already lost everything

except desire, the red heft of it

warming her outstretched palm.

Then there is this quick clip of an end to a poem written in 2015 by Ansel Elkins. The title is “Autobiography of Eve.”

Let it be known: I did not fall from grace.

I leapt

to freedom.

And finally, there is this lush, voluptuous piece from Marge Piercy, published in 1998, titled, “Applesauce for Eve:”

You are indeed the mother of invention,

the first scientist. Your name means

life: finite, dynamic, swimming against

the current of time, tasting, testing,

eating knowledge like any other nutrient.

We are all the children of your bright hunger.

We are all products of that first experiment,

for if death was the worm in that apple,

the seeds were freedom

and the flowering of choice.

When I read this last one, this one from Marge Piercy, I think: yes, this is the Unitarian Universalist Eve: Scientist. Life. Freedom. Hungry with curiosity.

I also look to the feminists (who are also sometimes the poets). In this case, I found such good, provocative stuff among the Jewish feminists. Not a surprise, really, but a joy and worth noting aloud. For instance, Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, writing just this past summer, believes the story of Eve to be revolutionary. She says it is so because it is the first

“story of breaking free of a partner’s expectations, of choosing to step outside a dynamic that may have been safe, and comfortable, … and following intuition, and the instinct for growth. Stepping out into the unknown. And even more than that—…this first brave act of free will becomes defining for humanity. This was the decision to choose understanding over blissful ignorance, engagement with the world and its pain instead of remaining in a comfortable bubble. This was the decision to learn and grow and face hard truths—even if doing so sometimes came with difficult consequences.”

Unitarian Universalist minister, Rev. Rachel Lonberg, suggests something similar: that Eve isn’t tricked into eating the fruit. She chooses it. Both she and Adam choose to live awake and self-aware. Rev. Lonberg tells us that god doesn’t create suffering as punishment. It just is part of the bargain: awareness of “all that is happening and thinking deeply about it, can be a source of pain.”

Frankly, it is through this awareness and suffering, that we gain the ability to know the difference between right and wrong, a defining aspect of what it means to be human. It raises the question of whether in paradise we could have ever been fully human.

There is so much to be learned from this freedom-seeking, bold Eve who is not interested in terrible calm. As Rabbi Ruttenberg writes

Eve teaches us that we can constantly strive to grow and to learn and to stretch ourselves, and that facing pain may be preferable to eternal avoidance of it. And that sometimes we can bring the people that we love along with us, if they’re willing to join.

There is so much to celebrate, rather than condemn, in Eve and her choices.

So again, I ask: whom does that old, malicious narrative serve?

It makes me think about that recent law in Texas, the one that other conservative states are actively trying to pass in their jurisdictions, the one that allows anyone (ANYONE!?!) to sue for $10,000 a woman who seeks the medical care known as abortion more than six weeks after conception (which is often before most women know we are pregnant). Or to sue people who help her – including a taxi driver, or I suppose, the person politely holding a door open on her journey from home to medical office.

There’s that bumper sticker: WWJD – what would Jesus do? I am wondering WWED – what would Eve do? Or WWLD – what would Lilith do?

I’m quite convinced that Eve would call BS on a law that bars access to necessary medical care for women, which is at least as important, if not more so, than access to the Tree of Knowledge.

I’m pretty sure that Lilith, who was turned into a demon held responsible for the death of thousands of infants, would be angry as all get out about women being demonized for terminating pregnancies and exercising autonomy over their own bodies.

I’d wager a fair sum that both Eve and Lilith, collectively, would support any efforts to help women in Texas (or other states) access full reproductive rights, including access to abortions they deem right and necessary for themselves. This includes any efforts we in this geographically-distant congregation make, for it is good to remember that we are near to an airport hub in a state where access to abortion is relatively protected; where we could perhaps offer refuge, refusing to acknowledge any authority that heinous law in Texas purports.

What did one of our poets, Ansel Elkins, say?

Let it be known: I did not fall from grace.

I leapt

to freedom.

So be it. See to it. Amen.

[1] Concept attributed to Gary Nahban in the original text by Kimmerer

Yes… what a well constructed, well researched and supported sermon. As juicy and rich as the seeds of that first forbidden pomegranate!

pomegranates for all!