Reverend Karen G. Johnston

The Unitarian Society

East Brunswick, NJ

September 27, 2020

While Buddhism asserts that we all have Buddhanature – that at our core can be found a golden goodness – the roots of Unitarianism or Universalism does not make this claim. Not quite.

Historically, Unitarians claimed that we have within us the capacity to be both good and bad and that we can BE good by DOING good, that we can build our character to achieve salvation, rather than it being reserved only for an elect few, as the Calvinists (and Hosea Ballou’s father) believed.

Historically, the thing that made Universalism heretical is that no matter how much good or bad we do, god loves us and will welcome us into heaven – kicking and screaming, if need be, as one of my colleagues has famously preached.

What does that mean for Unitarian Universalists today?

For months, this sermon had a different title in my head. It was “Marie’s Sermon,”

because during one of my June driveway visits, Marie Phelan, a member of this congregation, shared that she was struggling to find the inherent worth and dignity of a certain high placed politician, given all the pain and suffering he continues to cause. I knew she was not alone.

It IS easier to damn some people to hell.

Frankly, it is easier to know there will be an ultimate judge of good and bad, and to assume (or hope) that such judgement reflects our own.

It is easier to exclude someone from humanity – call them a monster, a demon, inhuman – when they do something terrible, rather than to tolerate the discomfort of knowing that person is within the same human family as we are.

The president of the Unitarian Universalist Association – the UUA – Rev. Susan Frederick Gray says “this is no time for a casual faith”. If we take Unitarian Universalism seriously, it is actually an exacting faith and always has been. This is true, even if we have a reputation for not knowing what we believe, or “religion lite,” or what our current congregation’s board president thought before he checked us out, decades ago: that we were the McDonald’s of religion.

Unitarian Universalism, with our First Principle asks ~ even demands ~ that we affirm the inherent worth and dignity of every individual. Every. Even at a time when there is so much violence and hatred being fomented by both bot and real persons alike; when there is much policy-based harm being perpetrated against the already vulnerable and marginalized, including some of us in this congregation; when hypocrisy is rife among our elected officials: this is a radical act.

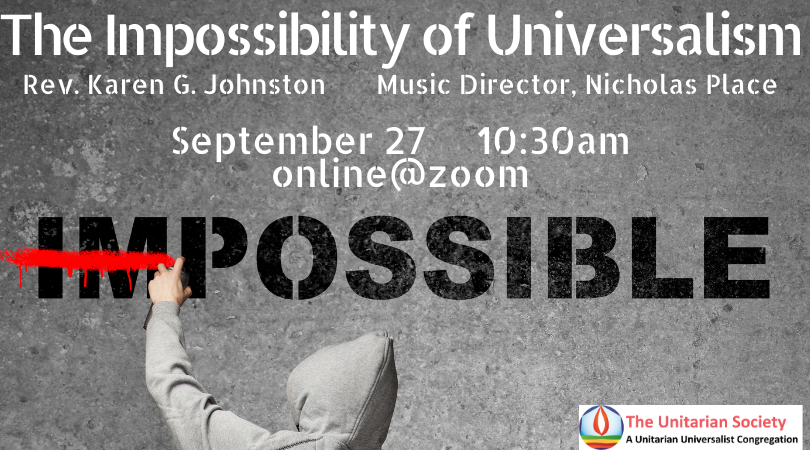

How to do this impossible thing? I’d like to ask you to reflect upon three things.

Number one: while each individual has inherent worth and dignity, not all behaviors do.

Our faith requires us to see the inherent worth of every one – the killer on death row, the hypocritical politician, the child molester – and it requires us to bring all our personal and institutional power to not only mitigate that person’s harms, but to stop them, if we can. Acceptance of inherent worth does not, and cannot, mean approval of harmful action.

The easy part of our First Principle is affirming as having inherent worth and dignity

of those individuals or identities that are so often the target of hate or derision – trans and nonbinary folx, atheists and so-called non-believers, family constellations outside the traditional, Black Lives Matter, undocumented immigrants. It feels good to be a First Principle people on those occasions.

Reverend Sofia Betancourt says it this way:

We are the theological inheritors of teachings on universal salvation. There is no winnowing out of the supposedly unworthy that can be named sacred among us.

It is our very Universalism that is at stake when we turn away from the impact that our institutions have on the same communities and groups that society encourages us to dehumanize and make small.[i]

This is absolutely where we should start. And it’s not where we should end. It is harder to be a First Principle person when we are face to face with someone who has assaulted us, or who has passed a law that demeans our humanity, or who has been cruel or violent towards another living creature.

Can we practice affirming their inherent worth and dignity while denouncing their action? Can we afford not to?

Number two: For, when we cannot perceive the inherent worth and dignity of another person, it is less a reflection of them, and more about us. It is possibly, and I say this as gently as possible, more of a comment on the depth of our own humanity, or perhaps our own experience of trauma,than on the humanity of the person we are judging.

Reverend angel kydo williams, ordained Zen Buddhist priest, says it this way:

White supremacy couldn’t survive if enough of us set about the work of reclaiming the human spirit, which includes reclaiming the sense of humanity of the people that are the current vehicles for those very forms of oppression.

It is the nearly or wholly impossible aspect of Universalism that calls us to see the humanity of the police officers who perpetrate brutality ~ or the humanity of white supremacist shooters like Dylan Roof. Yet in so doing, we are more able to access our own.

Even though I do not believe in either heaven or hell, I do take seriously the legacy of our Universalist ancestors: that god loves all (no matter how muddy we get) and that everyone will get into heaven. Everyone.

On some days, I don’t like it. I don’t like thinking that there won’t be an ultimate comeuppance. It seems utterly unfair.

I don’t like the hard heart work it requires of me. I don’t like to see myself regularly failing at this high standard set before me.

But then I inhale and I think of how so much of our common project is aspirational, that we must aim and aim again, not because we are failing, but because we are practicing.

I think about how long eternity is and how I want to affirm life, not destruction, not ugliness,not punishment ~ so I try again.

I think of how moved I am by the song we played earlier by Arjuna Griest,

and by this poem, from Andrea Gibson called, “Daytime, Somewhere” shared here in part:

So when asked if I think you’re a good person,

I say, I don’t believe in good people. I believe in people

Who are committed to knowing their own wounds intimately.

…

Truth knows everybody’s dark side is daytime somewhere.

Do you know science just proved an atom

can exist in two places at the same time?

No one is ever only at the scene of their crimes.

Each of us is always also somewhere holy.

If what we are called to do this thing that is both necessary, and impossible, what are we to do?

Number three: We pay attention to where our empathies linger and attach themselves.

Especially for those of us with identities of privilege – folks with white skin, folks who present as male, folks with economic protections and privileges, folks who have had positive experiences with law enforcement, folks living without physical ordevelopmental disabilities – it is easy to have our empathies collude with narratives that support systems of oppression. It is how we have been trained. It is how I have been trained.

For instance, I noticed the pathways of my empathy as I watched the video footage, released this week, of the fatal police shooting of Hasani Best in Asbury Park this past August.

I watched as the tension became so thick; as the police officers took attentive care of each other, making sure their shields would protect each other from assault by someone with a knife in his hand, screaming at them.

I noticed as the officers demonstrated few effective de-escalation skills, using words and tone of voice that only made things worse.

I heard the way that tension overflowed into nervous laughter coming from several of the officers, not out of disrespect but because human nervous systems work that way. I recognized it because that is something I have experienced in my own body when engaging fragile men with violent histories in high-tension situations.

And let me be clear: I saw no escalation in threatening behavior by Mr. Best at the time one of the officers pulled the trigger. Which means that I, and anyone who watches that recording, observed the unnecessary use of force that resulted in the death of another Black man.

Now Mr. Best is dead.

With his yelling, his violence towards his partner (which is why the police were there in the first place), even with his brandishing a knife: I affirm Hasani Best’s inherent worth and dignity. I say Black Lives Matter.

In their aggressive approach and in their fear for their own safety and that of their co-workers, I affirm the inherent worth and dignity of the law enforcement officers. This is what my faith calls me to.

And my faith also calls me to seek justice and equity in human relations (our Second Principle). As such, I join with Mr. Best’s family in calling for criminal charges in this case.

This is a lot to consider, so as I come to a close, let me break it down once more:

Number one: while not all actions have inherent worth, all persons do.

Number two: we demean our own humanity when we cannot see another’s.

Number three: pay attention where our empathy lingers and attaches itself – do our empathy support equity and justice in human relations?

Let us recognize that we all are covered with mud or hardened, ugly clay at times, that hides our best selves. Let us remember the poet’s words that

“No one is ever only at the scene of their crimes.

Each of us is always also somewhere holy.”

Amen.

[i] Rev. Sofia Betancourt, quoted in Widening Circles of Concern, p. 15