Do you know that old, and perhaps tired, and perhaps true, cartoon about Unitarian Universalists? There are two doors. Each has a sign over it. The first door says, “Heaven.” No one is going through that door. The second door says, “Seminar about Heaven.” All the Unitarian Universalists choose that one.

I want to begin with gratitude. Gratitude for so much, but especially for accepting the invitation to take part in our collective lectio divina. I was moved by what we created together, what we allowed to rise up from our voices mingling with each other’s, a surrender to whatever would come of it.

As you may have noticed, I am spending the year with the goal of preaching on the Unitarian Universalist principles – all seven plus one of them. Thus far, I have preached on Principles 7, 1, 8, 5 and 4, in that order. Today I am preaching the 3rd principle:

Acceptance of one another and encouragement to spiritual growth in our congregations.

But I am not just preaching on the topic. We, together, are exploring and practicing it. And doing it in our pluralist Unitarian Universalist fashion: informed by Christianity, Buddhism, and Sufism to find our way in. Today, together, we are saying yes to the first door – not of heaven, but of spiritual practice, trying it out in our meditation prayer today, in the lectio divina contemplative practice, not just attending a seminar about it.

~~~

Upekkha is the Pali word for equanimity. It is one of the four Great Virtues or Divine Abodes in Buddhism, along with

Metta – lovingkindness,

Karuna – compassion, and

Mudita – sympathetic joy.

It is what the meditation teacher was trying to grow within himself when he chose over and over again to bring the clumsy tea boy along. It is the capacity that the great Mystic and poet and Muslim, Rumi, is describing when he says to welcome all the hard stuff into the house of your soul, inviting them in laughing.

Equanimity is the quality of inner peace amidst change[i], disappointment, surprise, fear, reactivity, disgust. It’s not that you don’t feel or experience those things – you do. It’s that they have their place and no more. That they pass through without getting sticky and staying beyond what is necessary. It is the capacity to stay centered without judgment, without clinging (what some call craving or desire) or without aversion, avoidance, or denial.

The Zen Buddhist teacher, Roshi Joan Halifax, describes equanimity as “the capacity to be in touch with suffering and at the same time not be swept away by it. It is the strong back that supports the soft front of compassion.” Gosh, when you put it that way, I want some of that. I want all of that! So simple, but not by any means easy.

Another way to think about equanimity, is the famous lesson called the Second Arrow. Attributed to the Buddha, it is found in the original teachings of The Buddha once they were written down, which is a few centuries after he lived. In this case, this lesson was in the Sallatha Sutta.

The Buddha noted that a person feels pain and that this is like being shot by a single arrow. It hurts. It may cause injury. All this is true and real. However, the untrained or unpracticed person – that’s you, that’s me, that’s most of us – we do not respond to the pain of that one arrow. We react as if we have been hit by a second arrow: we bring fear, or anger, or worry — all sorts of secondary emotional reactions that amplify the pain, turning it into suffering. We might break our leg – that is the first arrow – but we turn pain into suffering by spinning stories of how we might not fully regain our strength or gait, or our livelihood might be impacted.

The Buddha said one can learn to feel just the one arrow. One can learn to not invite the second arrow. Our modern interpretation has boiled this lesson – and perhaps all the lessons of Buddhism – into this: pain is inevitable; suffering is optional. Equanimity allows us to experience the fullness of the first arrow, without adding a second (or third, or forth) arrow.

~~~

The poem we know as The Guest House comes to us from an epic, unfinished collection called, “Masnavi,” that contains 50,000 rhyming couplets. Rumi described the Masnavi as “the roots of the roots of the roots of religion”— which he understood was self-evident to mean Islam —“and the explainer of the Koran.”

Rumi, as you may know, was a 13th century scholar, poet, , a devoted student of the Qu’ran, and follower of the Mystic, Shams-i-Tabriz. He was born in what is now Afghanistan and eventually settled in Konya, in what is now Turkey.

There’s some information about this particular version of the poem that I think is important for us to know. This English version comes to us from Coleman Barks and is likely the most familiar in America.

Yet, the strange thing is, Barks does not read or write Persian, which is what the original verses were written in. Saying he is a translator is an overstatement. He’s more of an interpreter and not even first hand.

Let me share with you some of the direct translation of the original text, just so you can get a sense of the liberty that Coleman Barks took

This body, O youth, is a guest house: every morning a new guest comes running (into it).

Beware, do not say, “This (guest) is a burden to me,” for presently he will fly back into non-existence.

Whatsoever comes into thy heart from the invisible world is th(e)y guest: entertain it well!

In 2017, published in the New Yorker,[ii] Rozina Ali wrote on the erasure of Islam from the Western encounter with Rumi, noting Barks willful ignorance of Rumi’s ties to Islam is part of a long line of other Western translators over the centuries who removed Islamic cultural and religious particularities in the original texts, while leaving in references to those shared with Christianity. She quotes a Rutgers professor, Jawid Mojaddedi, who states,

“The Rumi that people love is very beautiful in English, and the price you pay is to cut the culture and religion.”

~~~

I hope that before you leave this morning, you will make the time to look at the painting of the poem which is a part of my family. I am no longer sure how old it is. I hope that it conveys the essence of the house metaphor for equanimity.

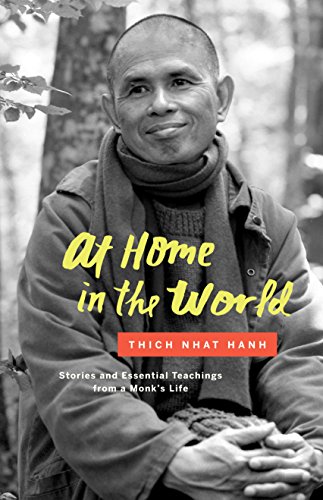

That metaphor — of house — for the encounter with equanimity is a powerful one that transcends wisdom traditions. For instance, the Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, in his book about equanimity, At Home in the World, writes

“Our true home is the present moment, whatever is happening right here and now. Our true home is a place without discrimination [or] hatred. Our true home is the place where we are no longer seeking [or] yearning for anything, no longer regretting anything…. [Our] true home is something [we] have to create for [ourselves]. When we know how to make peace with our body, to take care of [it] and release [its] tension, then our body becomes a comfortable, peaceful home to come back to in the present moment. When we know how to take care of our feelings—when we know how to generate joy and happiness, and how to handle a painful feeling—we can cultivate and restore a happy home in the present moment. And when we know how to generate the energies of understanding and compassion, our home will be a very cozy, pleasant place to come back to…. Home is not something to hope for, but to cultivate….”

Home is not something to hope for, but to cultivate. Equanimity is not something to hope for, but to cultivate. In this, I hear the work of spiritual practice. In this, I sense the fruit of spiritual growth. Not the low bar of spiritual satisfaction that the congregation’s Bond of Union names. Just sayin’.

~~~

I want to offer you an example from my own life, hoping that it may be of service to you in yours, then connect to why growing our capacity for equanimity might be of service to us as a whole.

As some of you know, I have the world’s greatest dog living at my house.

Vera.

I know those of you who have dogs think you have the world’s greatest dog living with you, and it may be true, too.

Anyway, Vera, while the world’s greatest dog, is not perfect. She has a habit, nearly compulsive by my standards, of licking herself. Constantly. Most of the time, I can shut it off. She likes to be near me. And when I sit myself down to meditate, she settles in nearby and begins her practice – perhaps her spiritual practice, I haven’t asked her – of licking.

Incessantly licking. Never-ending licking. Unremitting, persistent, ceaseless. You get the idea. No matter how much I come back to my breath, bring my attention away from Vera or the sound, it does not seem to work. My nervous system is drawn in and I grow increasingly reactive to that. sound. Often it results in my impulsively breaking my silence, impulsively raising my voice, and impulsively commanding her to stop.

Vera does not like that voice. Neither do I. (It does get her to stop, though.)

I am working on this in two ways right now. One is that I am trying to move from impulse to intention. If I must break my silence, if I must issue a command, then there is an increased elegance if I do it with intention, rather than with impulse.

The second way I am working on this is recognizing that there is space between me and my nervous system. It is my nervous system that is reacting so strongly to the sound of her licking. It is my nervous system that feels a growing sense of desperation that if the sound does not stop I will somehow – and I’m exaggerating here for effect – disintegrate.

So, if I can both know that I am not nervous system and that my nervous system is not the whole of me, then I might be able to experience something closer to equanimity. That can begin when I can observe even a moment’s pause between the trigger – Vera’s licking – and my reaction. Then I can slow down, I can choose something that might soothe my nervous system.

It might be getting Vera to stop. Like the hosts of that ancient meditation teacher suggested by not including the clumsy tea boy along on trips anymore. That’s an external solution and sometimes we need them. Sometimes we need to remove external triggers from our lives – or remove ourselves from exposure to them.

And we also need to identify and grow the capacity for internal strategies. Observing our reactions and trying to get under them, or before them, in order to possibly interrupt them. Learning how to use breathing as a means of self-regulation. Or self-talk.

Or somatic strategies that can bring us to center, that can help us touch that sense of home that Thich Nhat Hanh named, that can help us – and this is the advanced version – stand at the door laughing and invite in that trigger – for me, invite in Vera’s incessant licking. This is why I don’t just close my door and not allow her into the room with me when I sit down to meditate. She is my clumsy tea boy right now (and I have other clumsy tea boys in our lives – most of us have more than one). I want to learn what it is she has to teach me.

The thing is, when I develop this capacity for equanimity in the small and perhaps silly circumstance of irritation at my dog’s compulsive behavior, I am growing my capacity in other, much more urgent situations, where the need for my thoughtful, skillful, intentional response has bigger consequences – in my family life, in my relationships, in our shared congregational life, in the midst of the mounting anxiety provided by a world inhabited by climate crisis, deep cultural divides, weaponized acts of hate, and a federal government that continues its dangerous dalliance with an authoritarian demagogue.

When we increase our capacity for equanimity, we know better how to move in that space between brittle reactivity and numbed-out avoidance, which is a form of resilience for us as individuals and us as a community. Equanimity allows us to stay engaged without being on one hand, overwhelmed or oversaturated or overstimulated or, on the other hand, using privilege to remove ourselves from the chaos. If this is the case, then it strikes me that equanimity just may be a necessary super power when it comes to the increasing threats to democracy, as well as what we are facing when it comes to the climate crisis. I’ll be preaching about that on the 23rd of this month.

~~~

May we choose the door of spiritual practice, not just learning about them.

May you never forget that you are the golden thread running through. That even in times when love feels opaque and distant, you can find your breath, you can find this community, you can find the deeper truth that all changes change.

In that midst, may you give yourself kindness and heaping, joyful love to get yourself through.

May you refrain from that second arrow. May we all refrain from that second arrow.

May we find ourselves at the door laughing, entertaining the hard stuff as a path is cleared for some new delight.

May we cultivate the super power of the Middle Way in ourselves, in each other, and in the worlds we inhabit.

Amen. Blessed be.