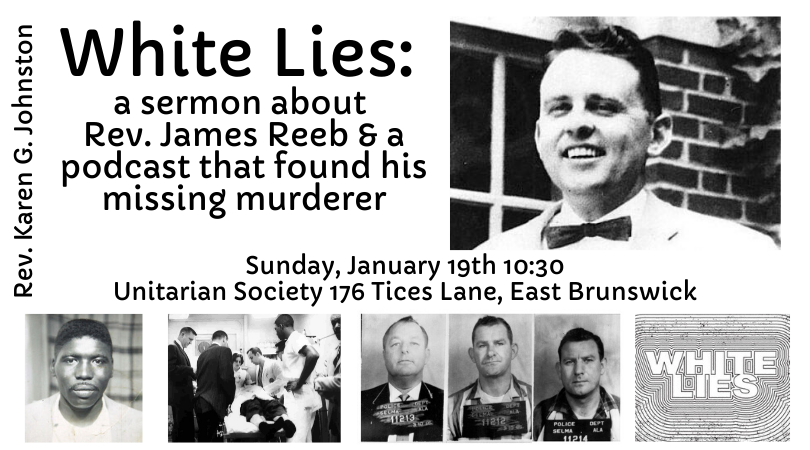

January 19, 2020

The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

[a clip 1:17 minutes from the White Lies podcast, episode, “A Dangerous Kind of Self Delusion”]

…Why must good men die for doing good? “O Jerusalem, why did you murder the prophets and persecute those who come to preach your salvation?”[i]

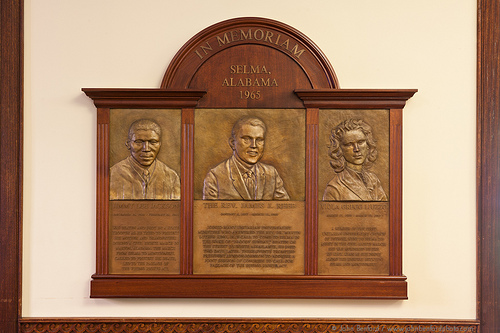

These words, along with those that Marie shared with us in our earlier reading, come from the eulogy that Dr. King gave at the memorial service for Reverend James Reeb. Dr. King admonishes us not to look just for the actual persons who held the weapons and inflicted the mortal blow, but to the system that led, and allowed, and actively cultivated such murder. Don’t look just to WHO killed James Reeb, but WHAT killed him.

It might seem that the two journalists behind the White Lies podcast did not heed Dr. King’s words, because they went looking into the mystery of why no one was held to account for the brutal murder.

However, by returning to this violent history, they are exercising what is called, liberatory memory[ii]. And they have extended to us the invitation to do the same: to liberate our history from a lie and out of that, possibly be saved by the truth. And if not saved, then healed. And if not healed, then to experience a sense of integrity that might allow for a more resilient future.

~~~

Originally Presbyterian, James Reeb turned to Unitarianism after seminary. He was a minister in our faith tradition, drawn by our focus on social justice. Reeb, and his wife, Marie, had four young children. They were committed to do what was theirs to do to resist racism. In the different cities where they lived – Philadelphia, Washington DC, Boston –as a white family, they chose to live in neighborhoods where Black people lived, despite segregated neighborhoods in these Northern cities.

We just heard part of his last sermon, which he gave at All Souls in Washington, DC, where he served as assistant minister. Longing to do community organizing, he left that position, unsatisfied with parish ministry. He ended up working for affordable and integrated housing, moving to Boston. Here is a small window into that new life, from a letter a friend[iii], dated the fall of 1964. I share it with you so you can remember the man alive, not just the martyr made:

It took me many days of looking to find this house. It has three floors, 11 rooms and full basement plus a vacant lot across the street. Almost no one wants to encourage you to move here. One lady asked me if I was crazy when I told her I really wanted to move into the neighborhood. The children are in school and, in general, happy. John wanted to help to integrate his class. Some gal in Washington wanted to know if I really wanted my children to go to school with Negroes and I said yes, of course, all children are lucky who integrate schools.

Marie is busy, getting the house in order. I am faced every day to stretch my mind. There are new problems, new ideas, new experiences to deal with. I have seized the bull by the horns. I am doing what seems important. And let the damn torpedoes come.

We have a challenge to meet as a family. We are together sharing in what I think will probably be one of the most significant times in our lives. We are all amazingly well and I am spending more time with the family than ever before. We have finally got our ping pong table and Marie, John, and I play regularly. We are resuming our Friday night birthday festival: we have a cake, candles, and someone tells us about a person we admire, and we sing happy birthday.

Just a few months later came Bloody Sunday – the violent encounter between police and marchers from Selma to Montgomery – immediately after which Dr. King to put out the call to clergy across the nation and from all traditions to come to Selma. Which Reverend Reeb accepted.

~~~

Chip Brantley and Andrew Beck Grace are both journalists. Brantley is a professor at the University of Alabama. Beck Grace is behind something called Moon Winx Films. They are the authors of the White Lies podcast published by NPR in May and June of last year. Both are Alabama-born white men whose families go back in that state before it was a state; families that had been slave-holding and Confederate.

I’m not a fan of the true-crimes genre of most anything, but this podcast, with its intersection with Unitarian Universalist history, captured my attention. It was riveting. And even though this sermon contains spoilers, it is well worth your time to listen to. According to its makers, the podcast is

“the story of a murder at the center of the civil rights movement and the lies that kept it from being solved. It’s an event that rippled far beyond the time and place where it happened, sparking national outrage and galvanizing support for one of the most significant laws of the 20th century.”

It is also an exploration into what happens when, in their words, “you call a lie and lie” and “find out what it means to live into that truth.”

~~~

James Reeb, along with other Unitarian Universalist clergy, arrived in Selma. That very evening, hungry for dinner, he and two other UU ministers – Orloff Miller and Clark Olsen – ate at a Black-owned diner. As civil rights workers, they were welcome there in a way they would not be at a white-owned diner. As they were departing the diner, in a town unfamiliar to them, heading back to the organizing headquarters, they chose a route that brought them in harm’s way.

Ultimately, three men would be arrested and charged, and quickly acquitted, for the beating that mortally wounded James Reeb on the street near that diner. Initial reports said there were four men involved in the beating. It is through the journalism of the White Lies podcast fifty years after the fact that the fourth man, never charged, is identified! The podcast also establishes it was Elmer Cook, one of the three originally arrested, who was the man who swung the club that crushed Reeb’s skull.

The night of the beating, during a harrowing ambulance ride to Birmingham, for there was inadequate medical care in Selma, Reeb lost consciousness and never regained it. A few hours later, his wife was called before she would hear about it on the 11 o’clock news: you must come. The national and world media was watching, as was President Johnson and Lady Bird. Two days later, Reverend James Reeb died.

~~~

Out of this act of brutality, out of the culture of that place and time and system of justice, there arose a counter narrative of what happened. While there was no denying the death, a story arose that he did not die from the beating outside the diner, but because the people with him in the ambulance – his colleagues and friends – inflicted an injury that led to his death.

He died, they would say, because the movement needed a martyr.

This was not just some vague rumor or personal rationalization that the four men who beat the civil rights workers told themselves and their families (although they did do that). This was the narrative that the prosecutor used in the courtroom, that secured the defendants’ acquittal. In the podcast, Beck Grace and Brantley interview the only surviving juror from that case, who says that he still very much believes that Reeb was killed by his friends and by the movement. It was chilling.

This is not the only time of such a nefarious counter narrative arose during civil rights struggles. Surely you remember the church bombing in Birmingham in 1963, the one that killed four little girls and maimed one? There was a widely disseminated – in the white community – that the church had bombed itself. It had staying power until 1977, when then prosecutor, Doug Jones, now Senator Doug Jones, won the case against the actual bomber.

Though not as violent, but made of the same dangerous cloth, I think of the modern myth of the so-called transgender person – a person dressed as a woman who is really a man who goes into women’s bathrooms in order to creep on little girls and vulnerable women. To my knowledge, there is no verified account of this happening, even though there are many substantiated cases of harm being threatened and inflicted on true transgender people just trying to pee. Yet the myth is perpetuated and transphobia grows.

To what lengths will we humans go to avoid culpability for our own evil? To rationalize our own bigotry and ignorance? It’s chilling.

~~~

In the podcast, they tell of the local cemetery in Selma, how there is a Confederate memorial circle with glorification of the fallen soldiers in the civil war. There is one statute erected thirteen years after the war ended – like many others throughout the South, and the North, trying to make meaning after that horrific event.

There is another statue, erected much later. This one is of Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first Grand Wizards of the Ku Klux Klan, a slave trader himself. This statue was erected weeks after the first Black mayor of Selma took office. It was not a response to a war that had just concluded. It was a response to a Black person holding political office. It was the KKK saying, we’re still here. Want to guess what year that was?

The year 2000.

I want to caution us. Today’s sermon is about a story that took place in Selma, Alabama, it is true. And in the story, we can see how that particular place struggles with history and memory in a particularly Southern way. This is also true.

But let us not be arrogant or find ourselves wallowing in false exceptionalism. There is no integrity in living such a life. There is no liberation there. The North has our versions of whitewashed lies. It is on us to call these lies the lies.

Perhaps you have heard of the concept of Sankofa. That word comes to us from Ghana, from the Twi language. It translates as “go back and get it.” It calls us to acts of “liberatory memory”: to look back to the past in order to learn for the future; to do so that we might liberate ourselves and others from some of the shackles of history – harm done, harm experienced, lies told, truths buried. The Sankofa symbol is a bird. Its body faces forward. Its head turns back. In its beak is an egg – fragile, precious, full of potential: the seed of knowledge from facing our past that we plant for a resilient future. A future with integrity.

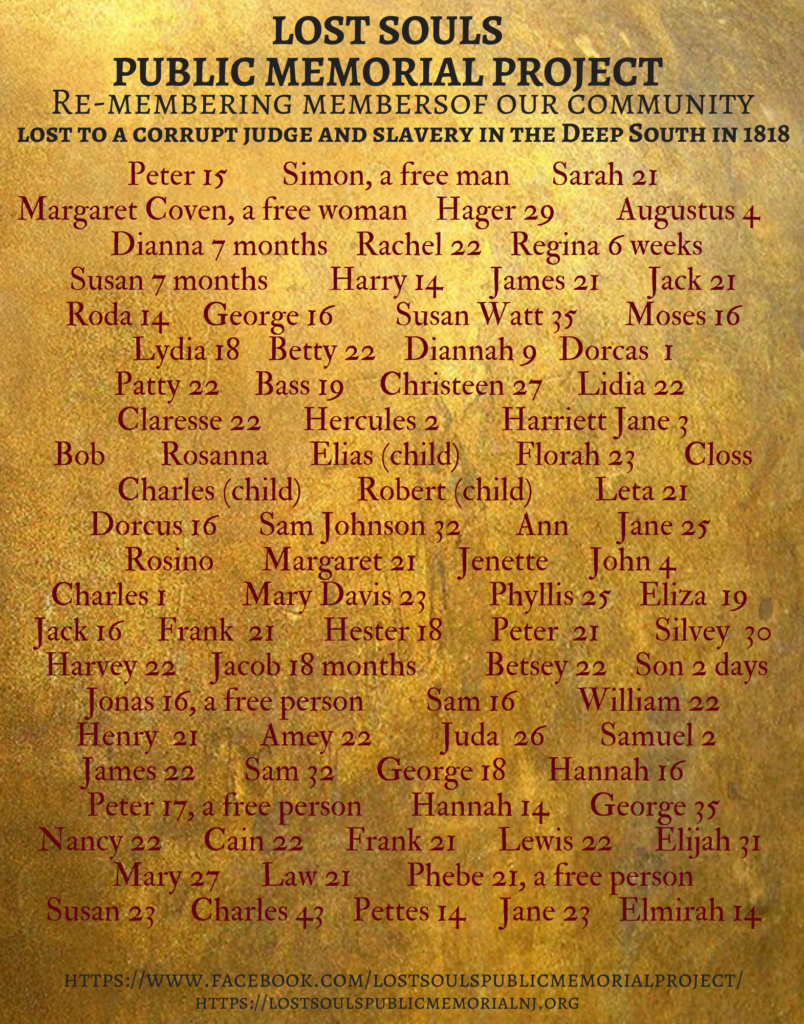

The Lost Souls Public Memorial Project is our chance to exercise “liberatory memory.” It is our chance to call a lie a lie and learn to live with the truth of it. It is our chance to help others to do the same: to live a communal life of more integrity.

For some of you the following is new information. For some, this is an update. The Lost Souls Project is making known the horrific history of 1818. A corrupt Middlesex County judge, who resided in what is now East Brunswick, along with what turns out is a cadre of other people, sold enslaved and free African Americans into the Deep South and permanent slavery. We are currently aware of 180 of whom we have the names for 141. Just a month ago, we recovered three additional names. We have even discovered that the governor at the time was implicated. It’s chilling.

We call them the Lost Souls, though they were not so much lost as actively stolen away. We are trying to build a memorial with all their names, and the history, so that it can never be forgotten, or whitewashed. This spring we are developing the process for soliciting designs from artists and continuing community education. In fact, next Saturday, Peter Kahn and I are presenting, along with Kristal Langford, at the Elizabeth Public Library.

The Lost Souls Project is a multi-racial, grassroots group in partnership with two African American community groups and in conversation with the Township of East Brunswick. If you ever wonder how your life might be more multi-cultural, you might consider participating in this meaningful work. We consider Lost Souls a ministry of this congregation, which currently acts as the group’s fiscal sponsor, enabling them to receive two grants so far.

~~~

In its conclusion, the podcast acknowledges that in this case justice is never done. Three men were acquitted. The counter narrative blaming the victim and absolving the white community took deep root. The journalists identified the fourth man guilty of murder – yet, he died before any formal charges could be made.

The family of Elmer Cook knew he was involved in the beating, but they never acknowledged that his swinging the club caused Reeb’s death. That counter narrative – that lie — absolved their patriarch of murder. A white lie to be sure, but not the kind we might call innocuous or harmless.

Still, acts of liberatory memory came out of this journalistic exploration. Katie Cook, the great granddaughter of Elmer Cook, went to college and learned outside and beyond the counter narrative told in her family. Out of that, she went seeking. Eventually, she met with the daughter and granddaughter of James Reeb and practiced authentic curiosity and reconciliation.

Marie Reeb, James’ widow, had spent these fifty years not wanting to learn the names of the three who had been briefly arrested, for she did not want hate to grow in her heart. In the course of the podcast, for the first time since her husband’s death, Marie chose to listen to the story of that tragic night. Not to start growing hate, but to rest in truth.

There came even further reckoning. Katie’s grandfather – the youngest son of Elmer Cook – met with the podcast journalists. Despite a lifetime of holding fast to the counter narrative, he listened to what the journalists had to share and accepted as truth what they shared, opening himself to the possibility of healing, of liberation, of integrity. Opening his family, and his community, to that very same possibility.

Just as the podcast offers us as a society and a nation.

~~~

In his eulogy for James Reeb, Dr. King asked us to work passionately, unrelentingly, and to make the American dream a reality, so that Reverend Reeb did not die in vain.

Let us take to heart the words those words, along with the words of Reverend Reeb in his last sermon, that we not allow ourselves to succumb to any kind of dangerous self delusion about how long in the making a truly racially just world is.

Let us keep each other company, making each other brave enough to call a lie, a lie, and to live lives of ever deepening integrity.

Let us be like the Sankofa bird: willing to look back so that the future might be more resilient.

Amen. May it be so.

Deep gratitude to the White Lies podcast and

its makers.

[i] https://www.uuworld.org/articles/memoir-kings-eulogy-james-reeb

[ii] Chandre Gould and Verne Harris, https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/MEMORY_FOR_JUSTICE_2014v2.pdf

[iii] https://www.npr.org/2019/06/21/734713126/a-dangerous-kind-of-self-delusion