The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick

November 10, 2019

What if this darkness is not the darkness of the tomb, but the darkness of the womb? What if our America is not dead but a country still waiting to be born? What if the story of America is one long labor?

These are the words of American lawyer, activist, and follower of the Sikh faith, Valerie Kaur. She spoke them just after the 2016 presidential election. They have stayed in my head and heart ever since.

The darkness of the tomb could be the climate crisis. Or the rise of right-wing

nationalism throughout the world. Or corruption in our own nation. The rising

river of refugees seeking safe home all over the world. The growing violence towards trans women,

especially those of color, of anti-Semitism in this country. The rise of gun

violence in this land. So many kinds of suffering, so much danger:

take your pick.

All over the world, there are democratic uprisings happening – RIGHT NOW. Are these labor contractions? Chile. Lebanon with the human chain of people across the length of the whole country and protestors singing Baby Shark to an upset toddler to calm him down. Haiti. Hong Kong with crowds somewhere between one and two million people joining in protest. Ecuador. Iraq. Iraq? Yes, even there. Are these the darkness not of the tomb, but of the womb, new possibilities about to be birthed?

Have you heard of the 1619 Project? Headed by Nikole Hannah-Jones, it is a project of the New York Times, focusing our national attention on the commemoration of the 400years since the first enslaved Africans arrived on the shores of this continent, ushering in the second existential threat to aspirations of true democracy (the first being the violent displacement of the original residents of the continent).

In addition to a riveting podcast series, Hannah-Jones published an article in the Times that provocatively titled, “America wasn’t a democracy until Black people made it one.”

This is the part of the American story of democracy that squeezes the breath from me and stops me from calling us back to our roots, stops me from invoking our founding fathers, as if the problem today is that we have simply gone astray, as if slaveholding George Washington and Thomas Jefferson didn’t mean to own humans, to profit from their suffering.

What Langston Hughes described in his poem, Let America Be America Again, that we heard earlier is what the writer Parker Palmer calls the tragic gap – “the gap that will forever separate what is from what could and should be.”

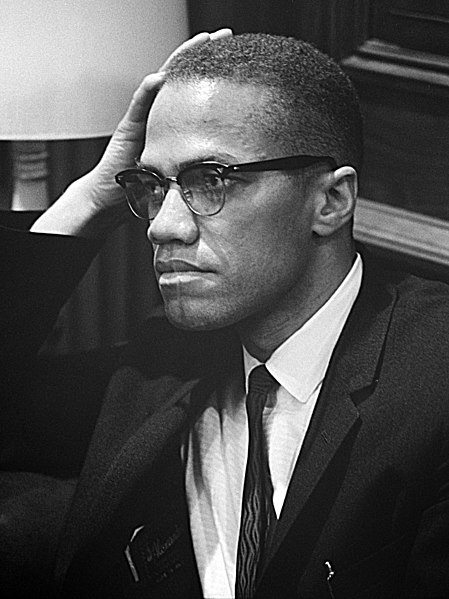

Malcolm X knew personally and up close the tragic gap. Only he called it something else: a sham. He did not think there was any tension between the lofty ideals of this nation and how Black people (or Native Americans, for that matter) were treated because he was clear that this gap, rather than tragic, was intentional and built into the system right from the start. He saw the core corruption in American democracy as fundamental, not something that could be reformed or fixed. And yet, he also wrote,

“Sometimes, I have dared to dream … that one day, history may even say that my voice—which disturbed the white man’s smugness, and his arrogance, and his complacency—that my voice helped to save America from a grave, possibly even fatal catastrophe,” Malcolm wrote.[i]

Sounds like Malcolm was also hoping not for the darkness of the tomb, but the darkness of the womb for American democracy.

Where there is a tragic gap, there are also paradoxes, in this American democracy. The paradox that the same darkness might be that of the tomb or the womb, depending on how we bring our attentions. The paradox (or is it irony?) that the very people enslaved and made less than human in this nation’s founding document become the agents of a truer democracy. Hannah-Jones writes,

The United States is a nation founded on both an ideal and a lie. Our Declaration of Independence, approved on July 4, 1776, proclaims that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” But the white men who drafted those words did not believe them to be true for the hundreds of thousands of black people in their midst. “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” did not apply to fully one-fifth of the country. Yet despite being violently denied the freedom and justice promised to all, black Americans believed fervently in the American creed. Through centuries of black resistance and protest, we have helped the country live up to its founding ideals. And not only for ourselves — black rights struggles paved the way for every other rights struggle, including women’s and gay rights, immigrant and disability rights.[ii]

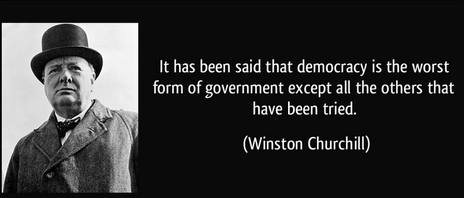

I struggled mightily to write this sermon. I silently cursed myself for thinking that the Sunday after Election Day would be a great fit for a sermon about democracy. I feel as if I must invoke in ALL CAPS the quote so often attributed to Winston Churchill:

In writing this sermon, I had to come face to face with my ambivalence about American democracy. In so doing, I came to understand that my intellectual ambivalence was a defense… against heartbreak – heart break at the lies I was told in school about the founding of this nation; heart break at how so deeply entrenched white supremacy was, has been, and still very much is in this land of not-all-are-free.

Yesterday, I was scheduled to attend the annual luncheon of the local NAACP – our nation’s largest civil rights organization. Even though this sermon was not yet done and I was fretting about it, I knew I had to attend because we are in partnership with the New Brunswick NAACP on the Lost Souls Project, and because last year they were generous to us, recognizing this congregation with their faith-based advocacy award. So, it was important that I go.

It was an unexpected gift and a salve, for I was given a visceral reminder of the resilience of a community of people who, despite the history of deep disenfranchisement and false promises of universal liberty and true racial equality, remain deeply committed to democratic ideals of full representation through participation in the 2020 census, registering people to vote, and overall engaged citizenship.

It was while sitting there that I began to see the many layers of democracy at play in our national landscape.

Writer and environmental activist, Terry Tempest Williams tells us that

The human heart is the first home of democracy. It is where we embrace our questions: Can we be equitable? Can we be generous? Can we listen with our whole beings, not just our minds, and offer our attention rather than our opinion? And do we have enough resolve in our hearts to act courageously, relentlessly, without giving up, trusting our fellow citizens to join us in our determined pursuit-a living democracy?

Here we are again, with this question of attention. Can we offer our attention, not just our opinions, she says, when it comes to building the first home of democracy in the human heart?

Unitarian Universalism makes longstanding claim on democratic processes as ethical and moral values, not political ones. So much so that it is part of our Fifth Principle:

We…covenant to affirm and promote…the right of conscience and the use of democratic process within our congregations and in society at large.

So, there is the political layer of democracy – voting, representation, sitting on juries, and so on. Even, at least theoretically, having a healthy checks and balances system, including the three separate branches engaging with each other in respectful, healthy, transparent manners [pause].

Yet there is this other layer that Tempest Williams is getting at: an ethical/moral one. Which is to say, qualities informed by democratic impulses that reside within us as individuals and as groups. Parker Palmer has identified five habits of the heart for healing democracy – qualities and capacities that We the People are responsible for cultivating. They are

An understanding that we are all in this together;

An appreciation of the value of ‘otherness’;

An ability to hold tension in life-giving ways;

A sense of personal voice and agency; and

A capacity to create community.

Palmer believes, for a healthy political democracy, these qualities must reside within THIS human heart. He refuses to point to those people over there – groups of which we never seem to belong to but who are always responsible for all the problems.

Over and over, he comes back to himself, and asks the reader – asks me, asks you – to do the same. And he warns,

If American democracy fails, the ultimate cause will not be a foreign invasion or the power of big money or the greed and dishonesty of some elected officials or a military coup or the internal communist/socialist/ fascist takeover that keeps some Americans awake at night. It will happen because we—you and I—became so fearful of each other, of our differences and of the future, that we unraveled the civic community on which democracy depends, losing our power to resist all that threatens it and call it back to its highest form.

Palmer says we must be people who “know how to hold conflict inwardly in a manner that converts it into creativity, allowing it to pull them open to new ideas, new courses of action, and each other.” I raise this particular way of healing the heart of democracy to your attention because I think this is the very description of what it means to live in covenant with one another, the very description of what it means to be not a creedal religion, but a covenantal one, making this quality especially relevant to us as Unitarian Universalists.

*****

We are in the midst of a national election that holds the potential of the womb and of the tomb. Given the attacks on so many democratic institutions in the past few years, so much is on the line with the presidential election.

At our General Assembly in June, delegates democratically adopted a Statement of Conscience, “Our Democracy Uncorrupted,” that recognizes that democracy in this nation has always been compromised (think the Constitution’s 3/5 Compromise, which counted enslaved individuals as equal to 3/5 of a white property-owning man), and that we must nevertheless continuously strive for an uncorrupt democracy. Here we are again: paradox and tragic gap.

Restricted access to voting rights for felons and the disproportionate incarceration of Black and Brown people results in significant disenfranchisement in communities of color. It’s easy to see this as white supremacy’s continued evolution of the original disenfranchisement of people of the African diaspora. Yet, things are changing, at least in some places. Last year, there was much attention to Florida’s restoration of the right to vote to felons; currently, Georgia is considering it.

Here in New Jersey, you cannot vote if you are serving a prison sentence, or if you have been released but are parole, or if you are probation. This means that over 100,000 residents of the Garden State cannot vote. Half of these are Black, even though only 15% of the Jersey population is Black. No other state in the Northeast denies voting rights to as many people living in the community as does New Jersey.[iii] I was shocked when I learned this just a few weeks ago at the UU FaithAction New Jersey Issues conference.

The UUA is encouraging congregations to #UUtheVote, to foment engaged citizenry, noting that

“with the increasing control of our government by corporate and special interests, voter suppression, and the alarming rise of authoritarianism, we face many challenges to ensure democracy and a just society.

That’s the darkness of the tomb. Yet the statement continued with what sounds so much like the promise of the womb:

We also have seen a rise in people’s movements led by people of color, women, and others impacted by injustice, a rise in activism, and the election of progressive candidates. This is electoral justice.”[iv]

The UUA has resource – webinars and tips for how to help foment an engaged citizenry. The opportunities are there, should we choose to bring our individual or congregational attentions. How might we harness our connections with UU FaithAction? or with the New Brunswick NAACP chapter? Or our close proximity to Pennsylvania, a swing state? How might we do what is ours to do to close the tragic gap?

[pause]

Back in 2016, Valerie Kaur included these words in her speech-prayer:

What if all the mothers who came before us, who survived genocide and occupation, slavery and Jim Crow, racism and xenophobia and Islamophobia, political oppression and sexual assault, are standing behind us now, whispering in our ear: You are brave. What if this is our Great Contraction before we birth a new future?

May we live our lives knowing and acting on the belief that democracy is not something we have, but something we must do.

May tend to the legacy and wounds of this nation’s corrupt and racist origins, persisting at the painful work that will bring about a democracy that is truly inclusive, reparative, and life-giving.

May our hearts know the “alchemy that can turn suffering into community, … tension into an opening toward the common good.”

May we live our lives knowing that progress is “never permanent, will always be threatened and must be redoubled, restated, and reimagined if it is to survive.”

May we listen with our whole beings, not just our minds, and offer our attention rather than our opinion, all in service of healing the heart of democracy.

May we do all that we can, in the life given us, to lessen the tragic gap, that others and our descendants might know more compassion, more inclusion, more justice, more life.

Amen. Blessed be.

[i] https://www.commondreams.org/views/2015/02/02/malcolm-x-was-right-about-america

[ii] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/black-history-american-democracy.html

[iii] https://www.njisj.org/1844nomorereport2017

[iv] https://www.uua.org/liberty/electionreform