The Unitarian Society

East Brunswick, NJ

January 7, 2018

READING: God Gave Me a Word by Amy Petrie Shaw

A grandmother — who was not only the end of all arguments in his large extended family, but often the start of them as well. This is how Bryan Stevenson often begins his talks: with the story of his grandmother and her propensity to hug so hard… and so long… and then – because she wasn’t finished – would ask, hours later: do you still feel my hug?

A grandmother — who was not only the end of all arguments in his large extended family, but often the start of them as well. This is how Bryan Stevenson often begins his talks: with the story of his grandmother and her propensity to hug so hard… and so long… and then – because she wasn’t finished – would ask, hours later: do you still feel my hug?

Perhaps this is where he learned in such an embodied way about the importance of “getting proximate.”

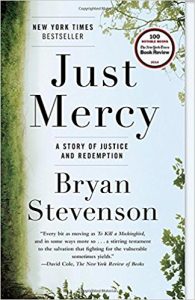

If you listen to this founder and Executive Director of Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama; author of the compelling book, Just Mercy, which I know some of you have read; this death row lawyer who represented dozens of prisoners, many of whom had been wrongly imprisoned, some of whom he was able to exonerate; this leader who has created a new “museum of conscience” called The National Memorial for Peace and Justice that will commemorate, lest we erase, the history of lynching in this country, that we might be liberated by its ghosts; if you listen to this man, you will hear that there are many reasons he believes the first thing we ALL must do is get more proximate.

That is the first of the four essential things that Bryan Stevenson, that lawyer, the man who gave the annual Ware Lecture at our annual gathering of Unitarian Universalists last June in New Orleans names. These four essential things are meant to bring about justice. They are four essential things to lend our weight, and the hefty weight of the Word of Love, in order to bend the moral arc of the universe towards what, my friends?

That is the first of the four essential things that Bryan Stevenson, that lawyer, the man who gave the annual Ware Lecture at our annual gathering of Unitarian Universalists last June in New Orleans names. These four essential things are meant to bring about justice. They are four essential things to lend our weight, and the hefty weight of the Word of Love, in order to bend the moral arc of the universe towards what, my friends?

Towards justice.

Perhaps feeling the insistent hug of this grandmother, herself the child of parents who had once been enslaved, Bryan Stevenson tells us to do four things:

Number One: Get proximate. Get closer to the people and places of suffering, to those things and people we each care most deeply about. Do not do your caring from a distance. Get out of the armchair. Do not do your expressing of outrage from a distance. Get away from the screens. Do not join in lamentation or give relief remotely. Do it up close. Closer than is convenient. Closer than feels familiar, at least at first. Closer than is polite (though choose consent, my friends: always choose consent.)

Number One: Get proximate. Get closer to the people and places of suffering, to those things and people we each care most deeply about. Do not do your caring from a distance. Get out of the armchair. Do not do your expressing of outrage from a distance. Get away from the screens. Do not join in lamentation or give relief remotely. Do it up close. Closer than is convenient. Closer than feels familiar, at least at first. Closer than is polite (though choose consent, my friends: always choose consent.)

Why? Well, the words on your order of service give a fine reason:

“When you experience mercy, you learn things that are hard to learn otherwise. You see things you can’t otherwise see; you hear things you can’t otherwise hear. You begin to recognize the humanity that resides in each of us.”

Mercy – giving it, receiving it – is only possible through close proximity. You may be able to forgive and forget from a distance, but you cannot grant or accept mercy unless you are right in the mess of things.

Number Two: to bring about justice, we must change the narrative. For Stevenson, with his history of working with death row inmates, of working with Black and Brown people whose actions have been disproportionately criminalized, it means believing — in head and heart — that no one – none of us — is wholly defined by the worst thing they have done.

This is also the same person using his MacArthur Genius grant to establish not only that National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial to our nation’s history of lynching, ostensibly scheduled to open on April 26 this year. What does it mean that a man who says “we are not defined by the worst thing we have done” is the founder of our nation’s first comprehensive memorial to lynching? With this, he is trying to change the narrative to make sure that by remembering such history we will, instead, be liberated by it, instead of living in this viscous morass in which we are doomed to repeat the sins of the past, in which we are repeating the sins of the past. I invite you to seek out – you can google it, or I will put a link to it in next Wednesday’s weekly eblast – the three-minute video clip that shows the artist’s representation of this memorial. It’s stunning. I have not yet had reason to want to go to Montgomery, but this new memorial, and its sibling new institution, The Legacy Museum, also opening around the same time, are giving me cause to change my mind.

We here in East Brunswick have special reason to be paying attention to the creation of new memorials. In fact, this Tuesday at 7pm – and you all are invited – we are having our next meeting to talk about what to do with this history of the Van Wickle Slave Ring and how we might build a memorial to its victims. And on Saturday evening, February 17 – mark your calendars now – we are hosting a community presentation with a local historian, someone from Rutgers who specializes in public history, and community members who want to change the narrative and build a memorial. I hope you will consider coming.

When Stevenson speaks about changing the narrative, he talks about living into the reality that there is always the possibility for change, for progress, for redemption. Closely aligned with our Universalist theology of a God called Love – can you still feel that hug from Bryan’s grandmother? do you still feel the weight of the Word around your neck? – a theology that asserts it is profound arrogance to suggest that any human act of sin could be greater than god’s loving capacity to forgive – ours, perhaps, but not god’s.

Number Three: Stay hopeful. Given the era in which we find ourselves, given the rising authoritarianism in the land, given the increase in hate crimes, given the skewed and lewd nature of our politics — Friends, we are living in a time when hope is utterly essential and downright difficult to find, much less sustain. Stay hopeful?

I don’t know about you, but for me, this is the hardest of the four. And so I compel myself to listen to these words from Stevenson, who straight out says that “hopelessness is the enemy of justice.”

So, when I am struggling to stay hopeful, or get to hopeful so that I can attempt to stay there, I think of the wisdom that comes to us from the twelve-step movement: fake it til you make it. Sometimes by acting hopeful, you find that you can come to feel the hope.

Of course, that is not enough, so I couple it with the practice of humility. Near the beginning of the first world war, Virginia Woolf wrote these words:

‘The future is dark, which is on the whole, the best thing the future can be, I think.’

She is using dark here not as terrible, but as unknowable. We humans confuse these things on all the time.

Perhaps I shouldn’t speak for you: I confuse these things on the daily. Not intending it as such, it is a form of arrogance, all the doom and gloom saying about the future that I can engage in – it’s as if my dismal certainty is preferable than not knowing. Preferable? I think it takes the cultivation of emotional intelligence, possibly through spiritual practice, to walk away from this particular form of arrogance. I’m trying. Every day, I promise you, I’m trying. And in my more spacious, ironic moments, I turn to these words from the author Rebecca Solnit:

“Again and again, far stranger things happen than the end of the world.”

“Again and again, far stranger things happen than the end of the world.”

So, stay hopeful, friends.

Number Four: Do uncomfortable things. Be willing to be uncomfortable. Really? Yes.

That heavy word of Love that god gave us – gave me, gave you, gives all of us if we are willing, even if only metaphorically – that’s not convenient by any stretch, not always comfortable, not if we are doing it right.

Uncomfortable might be a whole slew of things:

- Be the only one of your kind someplace – the only straight person in a gay bar; the only white person in a room that is full of people of color – and doing so with humility, curiosity, and respect.

- Be in a space where Spanish – or Hindi or Urdu — is the primary language and it’s not yours.

- If you are a man and in a room where decisions are being made, it’s staying silent, or ceding your turn to a woman or a gender non-conforming person.

- It’s using the pronoun “they” in its singular form, moving into the reality that the pronouns “he” and “she” are no longer sufficient for the beautiful human cacophony of diversity we experience.

Maybe doing uncomfortable things involves inviting uncomfortable feelings. Confusion or grief; some forms of shame or – and I say this as one white person to a room with many white people in it – our own white fragility – all these forms of discomfort can be a teacher. Some social theorists call it an interrupter, a positive thing because it is interrupting archaic habits and allowing new ones – new neurological thought patterns – to emerge. So number four asks us to welcome discomfort: it can be a gift.

~~~

This is by no means a linear list. These are not four distinct injunctions that you take separately, one at a time, in order, and then, voilá, you are somehow complete and done and get to rest on your laurels. I have come to believe that while each is its own, they are also very much interdependent and circle around to each other.

When I have gotten more proximate with, as Bryan Stevenson says, “a place or a people rich with suffering,” my unbidden fantasies of being noble are quickly replaced by the experience of discomfort, sometimes deeply so – uncomfortable with difference; uncomfortable because the rules for social interaction are upended; uncomfortable because I observe judgment or some other unbidden shadow rise up within me.

Or uncomfortable “sleeping” on a couch in an overheated room in a nearly empty building, my body on alert and so my sleep disrupted, yet being of greater service.

It is when I get proximate, even with that inconvenience or discomfort, that I also am more likely to experience that which makes me hopeful: I feel that I am being of use. Even if I am clumsy, having mustered the courage to attempt it, cultivates confidence and this, too, usually feeds hope.

When I am able to sustain a hopeful orientation to the world, the doom narrative that too often dwells inside me changes, and thus changes the narrative I spread in the wider world.

All this helps me carry around that heavy Word of Love, the one hanging from my neck, held in my mouth, burned into my heart as I get proximate with the poor and broken hearted, the queer boi or angry girl, closer to the man (and woman) with no papers.

Or with all of the screwed up and pushed over and too tired and the I can’t take no more’s.

And perhaps even – and here take a deep breath — the politician spewing hatred or the minister in the costume of a saint – though, my friends, that is infinitely harder.

Most definitely when I start moving to and with the saints and sinners and scramblers inbetween – that’s when it’s more likely that I can stay hopeful, when I am with the scramblers inbetween, when I am with my people, when I am with you, dear ones, when I am with you.

Amen. Blessed be.