The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

March 19, 2017

A compass, rather than a map.

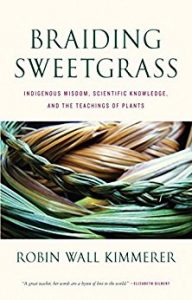

Last week I told you that I have been reading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Its subtitle is “Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants.” Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, a botanist, an academic, and poet. Her storytelling is exquisite.

That’s how Kimmerer describes the difference between indigenous spirituality and Judeo-Christianity. With its ten commandments, she suggests that the Abrahamic religions provide a map, with clear directions for right and wrong. What she was taught, is more like a compass: pointing folks in a direction, but then they have to find their way, each generation anew.

A compass, rather than a map.

When I heard that, a spark of recognition touched me. Unitarian Universalism also aims, in its essence as non-creedal religion, a religion without dogma, to be more of a compass, than a map.

Unitarian Universalism has its seven principles, one of which states that we have “a free and responsible search for truth and meaning.” So rather than a map, or even a GPS to tell us exactly where to go, recalculating as we take wrong turns, we have this principle that aims for an resilient balance between an individual’s free search and the responsibility we all hold within our covenantal community.

This is our work: using the compass of Unitarian Universalism to create a map for a life of integrity, a life in service of a greater good, a life that is whole and holy.

And this is where I believe that wisdom enters the picture.

What do I mean by wisdom? How do we distinguish between it and garden variety knowledge?

Where is wisdom to be found? Is it inside us? In our hearts?

Is it outside us? In our laws? Scriptures?

There are books in the Hebrew Bible that have been given the name, “Wisdom Literature:” the Book of Job (my favorite), Proverbs, Ecclesiastes. If wisdom resides there (and I happen to think some does), our Unitarian Universalism holds that it is not, by far, the only source.

To try to learn what wisdom is, I could have turned to the social sciences, perhaps an article from Psychology Today, based in research, attempting to quantify the qualities of wisdom. Such data-driven exploration would tell us that wisdom is

- Not correlated to age, but to the capacity for reflection

- connected to the ability to see shades of grey, rather than either/or

- balances self-interest and common good

- willing to challenge the status quo

- aims to understand, rather than judge

And does not guarantee more happiness: people considered by others as wise do not score higher on scales measuring happiness. Wisdom does strengthen one’s sense of purpose in the world. For a wise person, that would be enough.

Yet that was not the first place I turned. I turned to the poets. I can’t share with you all the poems from my research, but here is an excerpt from Mary Oliver’s In Blackwater Woods:

Every year

everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires

and the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.

Wisdom strikes me as knowledge saturated with humility, knowledge with its certainty tempered. This idea — of humility, of curiosity, of recognizing the need to learn — fits with botantist Kimmerer’s ideas:

“In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top—the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation—and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as “the younger brothers of Creation.”

We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn—we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance. Their wisdom is apparent in the way that they live. They teach us by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out.”

I have wondered about the role of generosity when it comes to wisdom. Is wisdom some form of knowledge shared generously? like Spider learned (the hard way)? Shared without attachment, knowing that it will evolve, that it is a process of ongoing co-creation, and will come to serve purposes beyond our current kin or ken?

Perhaps John, from today’s reading, with his generous idea of what it means to attend church, was a wise man. Since John Eric was one of the first people I met when I walked over the threshold of my first Unitarian Universalist congregation, lo these 22 years ago, I would have to say yes, he was. Certainly his efforts seemed informed by a balance between self-interest and common good, as mentioned by that social science data.

I have also wondered if wisdom is the capacity to see beyond the apparent, to see the sacred nature of a person or a thing or a place or a moment; to see interconnection and interdependence where others might only see individualism and competition? I think here of the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh and his teachings that we are here on this earth to awaken from the illusion of our separation. This, too, is an aspect of wisdom.

I have also wondered if wisdom is the capacity to see beyond the apparent, to see the sacred nature of a person or a thing or a place or a moment; to see interconnection and interdependence where others might only see individualism and competition? I think here of the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh and his teachings that we are here on this earth to awaken from the illusion of our separation. This, too, is an aspect of wisdom.

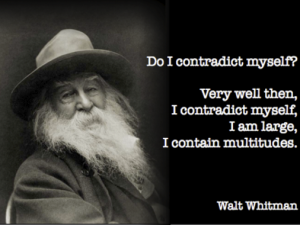

When I look at the wise ones whom I have encountered — in person or through stories — I find that they are people who can hold paradox loosely in their hands. They do not fall apart from the strain of contradiction, but are invigorated and inspired: moved to laugh with delight, or weep at its beauty. Their lives are lived-out versions of Walt Whitman’s declaration: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then. I contradict myself. I am large. I contain multitudes!”

There is the old story of Rabbi Simcha Bunim. It is said that in each pocket, he carried a slip of paper. On one he wrote: for my sake the world was created. Such grandiosity! On the other he wrote: I am but dust and ashes. Such humility! He carried both messages as a constant reminder. Holding paradox, loosely.

There is the old story of Rabbi Simcha Bunim. It is said that in each pocket, he carried a slip of paper. On one he wrote: for my sake the world was created. Such grandiosity! On the other he wrote: I am but dust and ashes. Such humility! He carried both messages as a constant reminder. Holding paradox, loosely.

A compass, rather than a map.

Kimmerer explores the relationship between scientific knowledge and spiritual wisdom, not seeing them as contradictions, but existing in reciprocal relationship. As a botanist and someone very much grounded in her spiritual heritage as indigenous person, she values science, though takes a dim view of “the scientific worldview,” which she does not believe can co-exist without harm.

I appreciate the distinction between these two concepts – Science and “the scientific world view.” While Science is key for Unitarian Universalists and our understanding the world, and is affirmed as one of our faith movement’s six sources, we must tread here carefully, for we have not always done so. Many late 19th and early 20th century Unitarians, like many so-thought forward thinking white folks at the time, were part of the Eugenics movement – full of science, but science that served racist belief systems, and became the breeding ground for Nazi ideology.

Kimmerer is eloquent about the distinction between those two concepts. She writes

Kimmerer is eloquent about the distinction between those two concepts. She writes

Science is the process of revealing the world through rational inquiry. The practice of doing real science brings the questioner into an unparalleled intimacy with nature fraught with wonder and creativity as we try to comprehend the mysteries of the more-than-human world. Trying to understand the life of another being or another system so unlike our own is often humbling and, for many scientists, is a deeply spiritual pursuit.

Contrasting with this is the scientific worldview, in which a culture uses the process of interpreting science in a cultural context that uses science and technology to reinforce reductionist, materialist economic and political agendas.

The practice of Science, at least as Kimmerer speaks of it, is one that raises up curiosity as a virtue, valuing it equally, and perhaps even more so than certainty.

So yes, we need to support Science, particularly when we see it under siege as evidenced by climate denial or being erased from our public schools. Yet we must also be cautious, for we can confuse Science for “the scientific worldview” and make the latter our god so much so that it prioritizes knowledge over wisdom, leading us like a GPS hellbent on arrogance and exceptionalism as our final destination.

A compass, rather than a map.

One last thing: in writing this sermon, I knew that I should try to answer the question of what wisdom looks like right now: early 21st century; a divided nation; lived experience of increasing climate constriction all over the globe and right here at home; unprecedented challenges to this American experiment in democracy; and the impact of all of these things on the most vulnerable among us. A compass, not a map, for every generation anew. I cannot and do not claim to be wise, so the following should be taken with that stipulation.

For me, wisdom looks like the following:

- Seeing proposed budgets not just as financial documents, but as moral and ethical statements, and acting accordingly.

- Living into the truth, quoted here by Nigerian writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “Every view is valued, as long as it does no harm.”

- Despite warnings from those who would subvert our most cherished values, persisting.

- Embodying the deep and abiding reality of the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part by showing up for those who are most vulnerable among us.

- Lastly, and by no means, leastly, remembering this: we were made for these times. Do not lose heart. None of us is alone.

A compass, rather than a map.

Blessed be. Amen.