The Unitarian Society, A Unitarian Universalist Congregation

East Brunswick, NJ

Not that long ago, a journalist suggested a parlor game to a group of historians. It was mid-summer: after the massacre in Orlando, after the attacks in Nice, after the shootings in Baton Rouge (and before the floods), after Brexit and Zika, in the midst of Syria,… This journalist, Rebecca Onion, was feeling capital-D Doom.

She was in good company. Perhaps yours. Sometimes I dip my feet into that well of doom. And not only because of these wide-ranging social and political hot messes, but also because of the burden of being human in this day and age: the scourges of addiction or dementia and how they take loved ones from us; the heavy weight of illness: cancer or Parkinsons; MS or chronic depression; the mundane grief of dear ones are mortal and die or are estranged from us. The list goes on; there are so many ways our hearts ache and break.

With regards to 2016, the Twitterverse and social media, with their relatively short attention spans, have been proclaiming that 2016 was the Worst. [period] Year. [period] Ever. [period] It’s not just Millennials, or Gen-Xers proclaiming this. This past week I was at a statewide conference of New Jersey clergy and an African American Pentecostal minister, a Baby Boomer, said that in all his sixty years, he wasn’t sure he’d seen much worse than what we are seeing now.

With regards to 2016, the Twitterverse and social media, with their relatively short attention spans, have been proclaiming that 2016 was the Worst. [period] Year. [period] Ever. [period] It’s not just Millennials, or Gen-Xers proclaiming this. This past week I was at a statewide conference of New Jersey clergy and an African American Pentecostal minister, a Baby Boomer, said that in all his sixty years, he wasn’t sure he’d seen much worse than what we are seeing now.

It has been a hard year, and more bad things have happened since that journalist wondered aloud “will 2016 end up in the history books as the worst ever?”

Responses from this non-scientific survey of historians started at 72,000 B.C.E. (when a volcano on the island of Sumatra erupted, creating a long night of darkness that lasted years and reduced the human population to between 3,000-10,000) then jumped to 1348 with the Black Death, which wiped out so many. The nineteenth century answers in the article revealed a distinctly American bias, naming both 1836 and 1877 for their distinct versions of our national reckless collision of racism and unfettered capitalism with legacies lasting into the present.

Then 1943 was named. Now, of course, there are well-remembered and widely-documented reasons why 1943 is a good candidate for worst year ever. By 1943, the Nazi machine had killed more than 1.3 million Jews. The Allies lacked the political will and military capacity to rescue the barely surviving European Jews still alive. But there are other reasons that only added to the weight behind this particular year: there was a famine in Bengal province in India, caused by the British exporting food to feed their soldiers. It killed an estimated three million people. (I had never heard of it before.) Here in the U.S., it was a time of deep racial unrest that many of us never learned about. That summer, there were over 240 reports of “interracial battles in cities and military bases.” There were the Zoot Suit riots in Los Angeles, as well as riots in Harlem and Detroit. In fact, Thurgood Marshall, who would go on to become the first African American justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, wrote a report in which he said, “Much of the blood spilled is on the hands of the Detroit police department.”

Sound familiar?

It’s not important to establish that right now is The Worst Ever in order for us to notice that things are profoundly bad.

We’re not talking these particular twelve consecutive months, but this general time period. We are seeing the largest forced human migration since the middle of last century. We are seeing this nation’s xenophobic and racist tendencies, everpresent in our national DNA, but now play a decidedly ugly role in our national presidential elections. Climate constriction makes itself known to more and more of us – impacting livelihoods and lives, the vulnerable among us unable to avoid the impact, but also the most protected (most, if not, all of us in this room) are beginning to be more than inconvenienced, and actually effected.

It’s enough to leave one with an overwhelming, sometimes paralyzing, sense of… well, I’m going to use the word again: doom. There are other words: helplessness. Hopelessness. Take your pick. And with any of them, we are left trying to extract deeper meaning. Or – if our lives allow us this option — diving back under the covers, because it’s all too much.

Perhaps there’s an elusive balance between these two. If so, I’ve not found it yet.

We all do need a break. A respite. A chance to turn off the clamor. I believe deeply in taking breaks – for you, for me, for everyone. There will be times when you and I will sit across from each other – perhaps in your home, perhaps in my office. You will tell me about your life, and I will listen. I will encourage you to say no to whatever is calling you, to take a break, to not take it all on, to let it go, to let someone else catch it, risking that it just might fall. And there will be times I will encourage you to say yes. There will be times when it won’t be me encouraging you to say yes, but this faith, this Unitarian Universalist set of value and principles we have claimed: they will be nudging you, calling you, urging you to say yes.

Yes, even when we think we aren’t ready for it, even when we think it’s not ours to do, even when we think that we already did our part and it’s someone else’s turn now, we still have to find it within ourselves to say yes. Yes when we feel doom. Yes when we are overwhelmed by the task. Yes when we feel overstretched by what our lives are putting on our plate. Yes when we are full of fear and helplessness and hopelessness.

Because it is in the yes-saying that we create new possibilities – some of them for the wider world, and some of them for who we understand ourselves to be. Because it is in the yes-saying that hopelessness stands any chance of turning into hope. Because it is in the yes-saying that helplessness turns to a sense of being able to make a difference.

I would be remiss here if I didn’t take this chance to speak to you about the Religious Education program here at TUS and my hope that more of you will say yes. After some significant set backs in the past year (the loss of two DREs, one planned and one not expected; no meetings of the RE Committee; difficulty having folks in the congregation commit to teaching), we are in a new place. We have a new DRE and we have a newly reconstituted RE Committee. Things are on the upswing, AND (not but) there is a serious need for teachers, without which there can be no RE program as we currently recognize it. The RE Committee, Jillian, and I have identified a model for teaching that we believe will allow connection and consistency for everyone, teachers and youth, and no need to teach every Sunday. Please speak to Jillian, or any member of the new RE Committee to explore this as a yes-saying possibility for you.

~~~

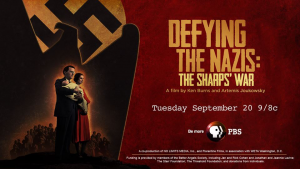

Let me switch gears here momentarily. This Tuesday evening, September 20, at 9pm, PBS is airing the documentary, Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War. Ken Burns – a name most of you likely recognize – produced the film and Artemis Joukowsky III, the grandson of the main protagonists, directed it.

Let me switch gears here momentarily. This Tuesday evening, September 20, at 9pm, PBS is airing the documentary, Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War. Ken Burns – a name most of you likely recognize – produced the film and Artemis Joukowsky III, the grandson of the main protagonists, directed it.

After seventeen other ministers were asked and refused, the vice president of the then American Unitarian Association phoned Reverend Sharp. The request? Would he lead “the first intervention against evil by the [Unitarian] denomination to be started immediately overseas”? It was 1939.

This is six years after Hitler rose to power. In this same year, there was a national poll on whether to increase immigration quotas, allowing more people fleeing fascist Europe into the United States. The American response? 83% were against letting more immigrants in. Sound familiar? This is the same year when the SS St. Louis, with 973 Jewish refugees seeking safety in the United States, were turned away – two hundred fifty perished in the Holocaust.

In that same year, however, well before the government of United States did, from his pulpit in Wellesley, Massachusetts, Reverend Sharp declared war on Hitler. This is part of who we, as Unitarian Universalists, are. This is our history.

Leaving their two young children in the care of family and congregants, both Waitstill and Martha together left on risky, months-long missions, eventually helping to provide safe passage for hundreds out of both Czechoslovakia and Vichy France. They are two of only five Americans listed as Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem, the memorial to the Holocaust in Jerusalem. This is an honor reserved for “those who actively risked their lives or their liberty for the express purpose of saving Jews from persecution and murder.” A highest honor.

Leaving their two young children in the care of family and congregants, both Waitstill and Martha together left on risky, months-long missions, eventually helping to provide safe passage for hundreds out of both Czechoslovakia and Vichy France. They are two of only five Americans listed as Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem, the memorial to the Holocaust in Jerusalem. This is an honor reserved for “those who actively risked their lives or their liberty for the express purpose of saving Jews from persecution and murder.” A highest honor.

We have reason to be proud that these organized actions against evil are the founding story behind our Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, an organization which continues its humanitarian efforts around the globe.

When I saw an early version of this film – back in 2012 at General Assembly – I was so moved by the story and the storytelling that I arranged for a community screening back home. I can only imagine that this new version, now with Ken Burns’ magic touch, and the voice of Tom Hanks as Waitstill, is just as powerful, if not more so. There are efforts underway to have a screening of this documentary at TUS. Even more exciting, we already have one interfaith partner – B’nai Tikvah in North Brunswick – which has agreed to co-sponsor this. So I hope we can get this event off the ground and hope that if we do, you will say yes to attending (and perhaps even yes to helping to make it happen – please talk to Kathy Scarborough if you are interested).

~~~

I was born six months before Dr. King was murdered; growing up, I always wondered what choices I would have made during the Civil Rights movement. Would I have become a freedom rider? Would I have stood up to racist comments or situations? I’d like to think so, but I’m not so sure. Perhaps you have asked yourselves a similar question – about that era or a different one.

Hearing stories of ordinary people making extraordinary choices can be inspiring. And sometimes, it has the effect of letting us off the hook. We hear a persuasive inner voice telling us that we aren’t that good, aren’t made of that mettle, aren’t that brave.

Just the other day, Reverend Meg Riley, the senior minister at the Church of the Larger Fellowship, our online UU community available to any and all, was reflecting on this. She suggested that instead of asking “Why aren’t I more like them?” or “What would I have done to try to stop the Holocaust?” we could ask these questions: “What are the gifts I bring to this world that I can offer for the common good?” and “What breaks my heart in the world today that cries out for me to help healing?”

I appreciate that shift in perspective – away from guilt and judgment and towards inspiration and connection. What are the gifts I can bring to the world for the common good? How is my heart breaking for this world and how might I help in healing?

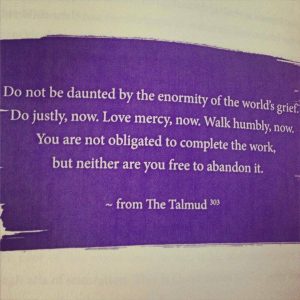

So in the face of that mounting Doom, the one from this year or others, or the future, I want to encourage us to turn to several of our world’s sources of wisdom to remind us that we can do that which is within our reach, that like the wise woman from the story said: it’s in our hands. Here, to help us, is wisdom from the Talmud, interpreted by Rabbi Tarfon, as Rabbi Rami Shapiro wrote:

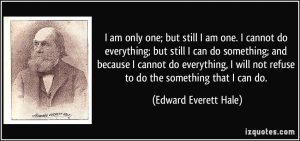

Here, to help us, is wisdom from Unitarian Universalist Edward Everett Hale, found in your grey hymnal:

Or this wisdom of our first hymn:

Or this wisdom of our first hymn:

many drops of water turn the mill, singly none, singly none.

Or what about the wisdom from our reading earlier in the service? “Do not lose heart. We were made for these times.”

What if that were our mantra? What if those were the words we spoke to ourselves and each other in the midst of facing daunting circumstances? Could we let go the guilt and the overwhelm, the rose-colored denial and the defensive cynicism, and find our gifts to the common good?

Survivor of the Nazi occupation in Hungary and professor of psychology, Ervin Staub tells us that, “Goodness, like evil, often begins in small steps. Heroes evolve; they aren’t born. Very often the rescuers make only a small commitment at the start – to hide someone for a day or two. But once they had taken that step, they began to see themselves differently, as someone who helps. What starts as mere willingness becomes intense involvement.”

(This dynamic need not apply only to facing evil. It applies to the Religious Education program: we do not need you to be a hero (sacrificing every Sunday morning to be a teacher). We do need you to begin with a small step of actively supporting the program with your time and being open to how the experience of serving the youth and families of this congregation might transform you.)

Let me end with more of Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ voice and her words of guidance on how to not lose heart in a storm, offering it to you as soothing salve:

…In any dark time, there is a tendency to veer toward fainting over how much is wrong or unmended in the world. Do not focus on that. Do not make yourself ill with overwhelm. There is a tendency too to fall into being weakened by perseverating on what is outside your reach, by what cannot yet be. Do not focus there. That is spending the wind without raising the sails. We are needed, that is all we can know. And though we meet resistance, we more so will meet great souls who will hail us, love us and guide us, and we will know them when they appear.

…In any dark time, there is a tendency to veer toward fainting over how much is wrong or unmended in the world. Do not focus on that. Do not make yourself ill with overwhelm. There is a tendency too to fall into being weakened by perseverating on what is outside your reach, by what cannot yet be. Do not focus there. That is spending the wind without raising the sails. We are needed, that is all we can know. And though we meet resistance, we more so will meet great souls who will hail us, love us and guide us, and we will know them when they appear.

…

… Ours is not the task of fixing the entire world all at once, but of stretching out to mend the part of the world that is within our reach. Any small, calm thing that one soul can do to help another soul, to assist some portion of this poor suffering world, will help immensely. It is not given to us to know which acts or by whom, will cause the critical mass to tip toward an enduring good. What is needed for dramatic change is an accumulation of acts — adding, adding to, adding more, continuing. We know that it does not take “everyone on Earth” to bring justice and peace, but only a small, determined group who will not give up during the first, second, or hundredth gale.

Blessed be. Amen.