Shouldn’t all sermons begin with a lava lamp metaphor?

Some of you have heard me refer to our process of moving from Principles to Values (and from Sources to Inspirations), using the metaphor of a lava lamp. It’s one of the first sermons I gave when I arrived here nearly two years ago and I have referenced it at least once since.

For those who haven’t heard it before, and even if you have, I invite you to imagine a lava lamp. Yes, that electrified mechanism that has an incandescent light bulb illuminating a sealed, transparent container that holds brightly-colored goo. When heated by said bulb, that brightly colored goo begins to undulate and rises, separating into smaller goo-groupings, that when they reach the top of their enclosure, they cool off just enough to fall back down, where they join the greater goo collective, becoming one goo unity, until the next cycle begins.

We can consider change and shifts, not just those at the current moment, but throughout the course of our history, as part of our cultural DNA, like a lava lamp cycle – the shape changes, but the content (that religious goo) stays the same. The shape is transient, but the content (the values) is permanent. (Or relatively permanent, given my Buddhist heart affirms that ALL things are impermanent.)

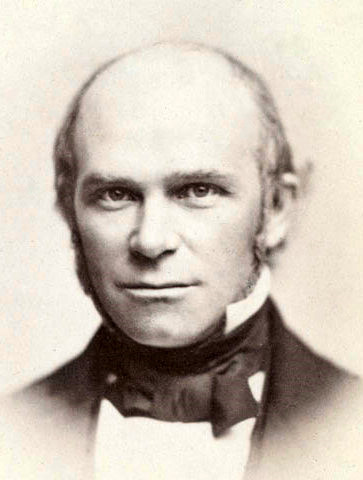

One of the twelve historical events we named in our earlier reading was the 1841 delivery of Theodore Parker’s most famous sermon, “The Transient and the Permanent in Christianity.” Parker was one of our most influential, and controversial, Unitarian ministers of the 19th century. Brilliant, self-taught, and at first welcomed as a Unitarian minister, ultimately his theology was not warmly received by the then-mainstream Unitarian views. While today we celebrate the 200th anniversary of the founding of the American Unitarian Association in 1825, he became unwelcome by the AUA, to which he offered a critique of the AUA’s 1853 “Proclamation of Unitarian Views.”

Not just controversial theologically, Parker was confusing socially and politically – not long before his early death at the age of 49, he became bedazzled with Romantic racial theory that was fed by what we today call white supremacy culture (Anglo-Saxons as superior), while also advocating for racial integration for churches and schools in Boston (yes, in the mid-19th century) while becoming a leading abolitionist, openly calling for people to defy the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (while most Boston Unitarian ministers kept quiet or endorsed the passage of that law). Yes: confusing.

His words are widely known, woven firmly into American culture, though not always attributed to him. For instance, that phrase that comes from Abraham Lincoln in 1863?

that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Well, in 1850, Theodore Parker, whose work Lincoln read studiously, gave a speech at an anti-slavery convention in which he defined “the American idea as”

“a democracy, that is, a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people ….”

And that phrase: “the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice” which is attributed to Dr. King? Well, Dr. King was quoting our Theodore Parker.

Why am I talking about Theodore Parker? Well, that famous sermon of his, On the Transient and the Permanent in Christianity, recognizes a form of shape-shifting that is inherent in all religious traditions practiced by humans.

His focus was on Christianity, yet this theological perspective can be applied to all religious traditions and is one that is seeped in humility. Basically, the message I take away from this 19th century sermon is that while there are things in the natural world, and in the divine realms, which are permanent, human articulations and conceptualizations are transient. For instance, he wrote,

Now the solar system as it exists, in fact is permanent, though the notions of Thales and Ptolemy, of Copernicus and Descartes about the system, prove transient, imperfect approximation to the true expression.

Though he would later change his mind, at the time of writing The Transient and the Permanent, he believed that the Word that Jesus shared was permanent, yet “what passes for Christianity with Popes and catechisms, with sects and churches, in the first century or the 19th century prove transient also.”

How does one know that anything is permanent? A fair question and one my Buddhist heart, with its understanding that all is impermanent, was regularly whispering in my ear as I read this classic text. According to Parker, the way we discern what is permanent is through the right of conscience:

If Christianity were true, we should still think it was so, not because its record was written by infallible pens; nor because it was lived out by an infallible leader, but that it is true, like the axiom of geometry, because it is true, and is to be tried by the oracle God places in the breast.

Parker declares that the oracle – the source of wisdom – that tells us what is true (what is permanent) is our own heart, what today we call the right of conscience. Of course, mostly what we know is the transient shape of our era, of our moment. How could it be otherwise? It is that transient shape within the warm lava lamp as it ascends and descends, its fleeting shape before it joins and rejoins the greater goo unity (that might be Parker’s permanence), which is outside our direct knowing.

This spiritual way of being in the world, according to Parker,

does not demand all [people] to think alike, but to think, uprightly, and get as near as possible at truth; not all [people] to live alike, but to live holy, and get as near as possible to life perfectly divine.

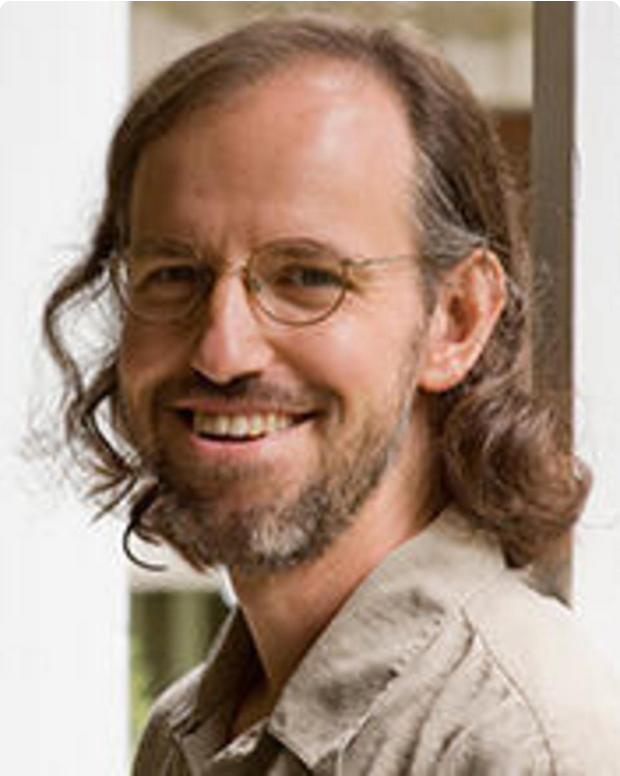

At the ordination of Reverend Rowan Van Ness last week, of which this congregation was a co-ordaining body, the sermon given by Dr. Dan McKanan shared some history of my home congregation, the Unitarian Society of Northampton and Florence. I raised my children in that congregation, living as we did in the village of Florence, so I knew the history intimately and proudly. I share it with you as part of this sermon on shape shifting – a term I borrow from Dr. McKanan – because it’s relevant to us here in Burlington and relevant to all Unitarian Universalists, especially at this moment in time.

The founding of the American Unitarian Association in 1825 – 200 years ago – did not satisfy all. It’s in our nature. As part of our ever-transforming faith movement, we are never satisfied. So it was then. So it is now.

And so, a decade and two after the declaration of Unitarianism, there were still liberal Christians in New England – some Unitarians, some Universalists, and even some of other denominations – who were deeply inspired by the story of Jesus and deeply uninspired by their experience in ordinary Christian, even liberal Christian, congregations.

They loved the Jesus of equality, peace and liberation and when they did not hear this from the pulpit, they shape-shifted. Rather than form a new congregation, they changed how they gathered: they build intentional communities. Not just worshipping together, but living together and working together. Multiple intentional communities were founded because they had different visions (and candidly, sometimes, even when they had a shared vision, because they could not come to agreement. Ah, humans being human!).

On land that is now Florence, Massachusetts, the Northampton Association of Education and Industry was formed in 1842. Dr. McKanan relates that it did okay – better than others – surviving for four years, though not long enough to pay off its debts.

Eventually, those who made up the Northampton Association gave up on the shape of a utopian community, but not on their values and vision. They shape shifted. Again.

This time, returning to the shape of congregational life, though this time without clergy, though they did have a Speaker, who held no special authority from any other. It was called the Free Congregational Society of Florence. It was non-denominational, though it did participate in the Free Religious Association that had been organized by Transcendentalists and abolitionists.

Was it worth it to shape shift TWICE? Wasn’t that a waste of time and energy? Dr. McKahan’s answer is absolutely not. He believes – as do I – that

“the people of Northampton unleashed amazing creativity BOTH when they were creating the intentional community AND when they were recreating the congregation.”

And that

“the true gift of the Northampton [and Florence] community … was not the form of the intentional community or of the congregation, but its willingness to shapeshift again and again in response to changing circumstances.”

Theodore Parker was alive and active as a minister on the other side of Massachusetts at the time of the Northampton Association for Education and Industry, as well as the founding of the Free Congregational Society of Florence. I think these words of his are a fitting blessing of sorts, lightly adapted for our modern sensibilities around inclusive language:

Let then the Transient pass, fleet, as it will, and may God send us some new manifestation of […] faith, that shall stir [people]’s hearts as they were never stirred; some new Word, which shall teach us what we are, and renew us all …

This past Easter, I preached on one of our core, Shared Values as Unitarian Universalists: Transformation. One of the ways we see Transformation in action in our religious lives is through shape-shifting (as Dr. McKanan calls it) or lava-lamping (as I describe it). Our history shows us that this is who we are. While some other traditions have whispered behind our backs (or shouted in our faces), both historically and present-day, that this is weakness (or worse: heretical, or outright sinful). However, we know differently. We know it is a superpower.

Like when, in 1894, we gathered in an liberal religious interfaith context and stirred controversy when we co-created a statement of purpose that did not place Christianity at the center and did not name god. Like when, in 1933, some of our ministers signed onto The Humanist Manifesto, affirming religious humanism and ultimately Unitarian Universalism inclusive of those who claim atheism or non-theism as their worldview.

One last story. Dr. McKanan’s sermon referenced the shape shifting story of the Confessing Church, those few Protestant churches in Nazi Germany who, despite initial hesitation, found themselves shape-shifting towards resistance in order to not be conformed into the National Socialist machine, as many Christian churches did under Hitler’s rule. That small group of religious resisters, some of whom paid the highest price, act as a role model for us in this era, no matter our religious heritage or identity, who seek a healthy, just and equitable democracy.

I close with these sobering and inspiring words from Dr. McKanan:

“These are, of course, perilous times for congregations. Like the members of the Confessing Church, we confront a new, cruel government that would like to destroy any institution that does not bend to its will. And like the founders of the Northampton Association, we live in a society shaped by centuries-old patterns of oppression from which some of us have benefited while others of us have suffered. In such a moment, shape shifting may feel risky. But together, always together, we might just find the new shape that our world needs.”