First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

December 8, 2024

I feel hope. I have hope. These are common ways to reference hope, to think about hope. Hope as a feeling. Hope almost as if it is a possession, a thing one can have or hold.

I feel hopeless. I don’t have hope. The flipside. The lack of feeling as if it’s out of our hands, something beyond our capacity to influence.

What if hope, and our relationship to it, can expand beyond this common understanding? What if we – you and I and us together – what if we might play with other possibilities? Even the possibility that the absence of hope – hopelessness – can have its up sides?

I first learned in seminary that the four Sundays before Christmas each have a theme for Advent: the last is joy, before it is love. Second (today) is peace. And the first is hope. So even though it’s out of order, and only the one, we are borrowing from last week’s Advent theme of hope for today’s service.

Two weeks ago, I mentioned this quote from the late Howard Zinn about hope and the future. That radical American historian reminded us that being hopeful can and should be informed by this truth:

The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.

Before exploring what hope is in the second part of this sermon, let’s explore three things that hope is not: hopium, optimism, and hopelessness. By saying what hope is not, my aim is for us to begin to map the territory and texture of hope, its edges and boundaries — helpful information about what hope is and can be.

First off: Hopium. Yes, you heard correctly. The combination of hope and opium points to false hope and its addictive qualities. Hopium. We might also call it toxic positivity. It’s what moves us to platitudes, which, more often than not, do not leave us feeling better, just feeling unheard and unseen.

Hopium may have good intentions, but it cannot withstand the shaking winds of truth or reality. It is fed by conflict avoidance and denial. When it comes down to it, it’s not really hope at all, but wishful thinking.

Next is Optimism. It’s easy to confuse optimism with Hope, but we do so at our own risk. Optimism is more like hope lite. It’s like junk food – it fills us up, temporarily, but it’s not sustaining (and it leaves us wanting more). The Czech statesman Václav Havel one said, “Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. [Hope] is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.” Optimism requires an unskillful certainty built on wishes – and that certainty can lead us to platitudes like “everything happens for a reason” or “god doesn’t give you more than you can handle.”

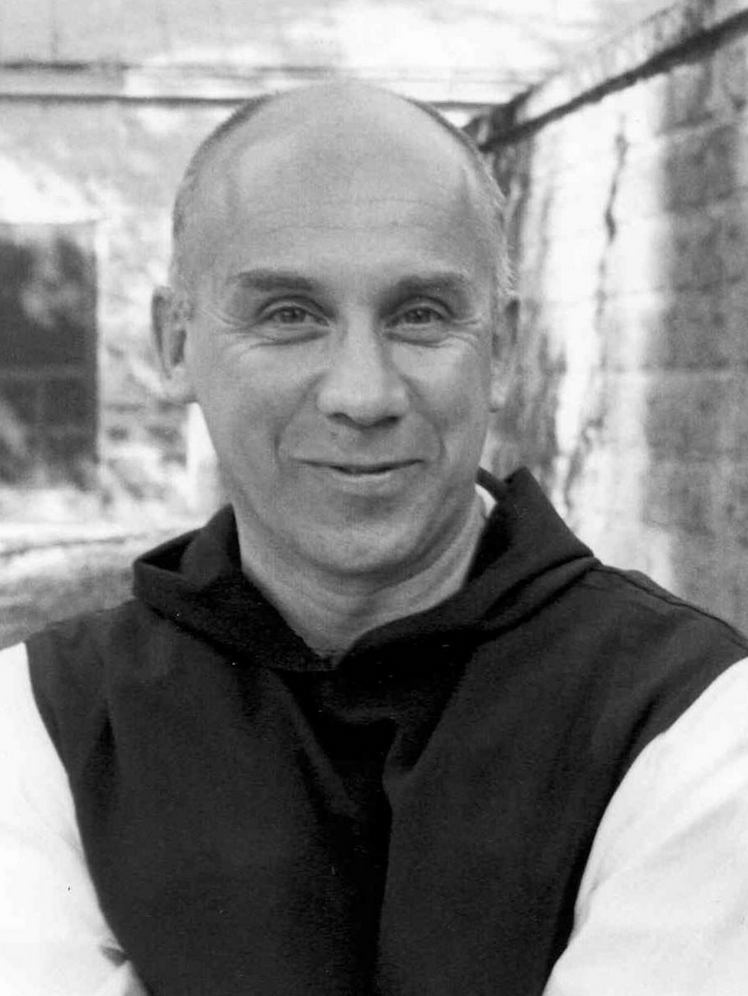

I am reminded of this quote from the Catholic mystic, Thomas Merton, which got me through one of the hardest times in my life:

Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.

To my ears, and perhaps you can hear it too, this rings like the lesson from the Good Luck/Bad Luck parable. We can’t always know if something that happens is a good thing or a bad thing.

The American cultural historian, Rebecca Solnit recently described hope in contrast to optimism:

Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists adopt the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting.

I ask you to remember that, because we’ll hear from Solnit again later.

Thirdly: Hopelessness.

Christian theologian, Dr. Miguel De La Torre, published a book in 2017 entitled Embracing Hopelessness. He suggests that until we have experienced hopelessness, it’s too easy for humans, and especially those of us with privilege, to opt for our own comfort, confusing it for hope. De La Torre’s hopelessness “rejects quick and easy fixes that […] temporarily soothe the conscious of the privileged.”

He believes that hopelessness propels all of us towards praxis – a form of action and reflection and then action informed by that reflection. He encourages us to choose hopelessness over that kind of hope that might move us to seek comfort and stop there. He says,

The disenfranchised have no option but to continue their struggle for justice regardless of the odds against them.

They continue to struggle whether hope is available or not. And so, he says, should we. His conviction calls to mind the concluding line from a Jennifer Wellwood poem:

Let’s dance the wild dance of no hope!

I think there may be something useful for us here.

What happens when we are not feeling hopeful? when we do not have hope? when we do not feel hope?

I ask these questions because many of us are struggling with hope and our relationship to it. I include myself here, but that’s kinda par for the course. I think it’s my nature to struggle with reconciling hope and truth. I think that’s why these words from the poet Andrea Gibson causes me holy pause:

What if… hopelessness opens up that space of unknowing? What if… uncertainty is where hope lives? What if so much of what we have been fed about hope is wrong – platitudes and false nourishment? What if common hope is cheap hope is Hope Lite is ordinary hope is something that cannot sustain us?

even when the truth isn’t hopeful / the telling of it is

And…what if there is something different? With more depth? More breadth? For that, I will see you on the other side for part two.

Part II

If common hope is insufficient, what texture and topography of hope might be not only sufficient, but radiant and nourishing and transcendent? Let me suggest a multiplicity angles in hopes (ha!) at least one resonates with you:

Wise Hope.

Hope as Practice.

Hope as Action in Community.

Hope as Love.

Wise Hope. In Buddhism, hope is often seen as a form of craving – a wish for something other than what is. Or it can sound like we are clinging to a certainty that everything will be alright, when the future cannot be known.

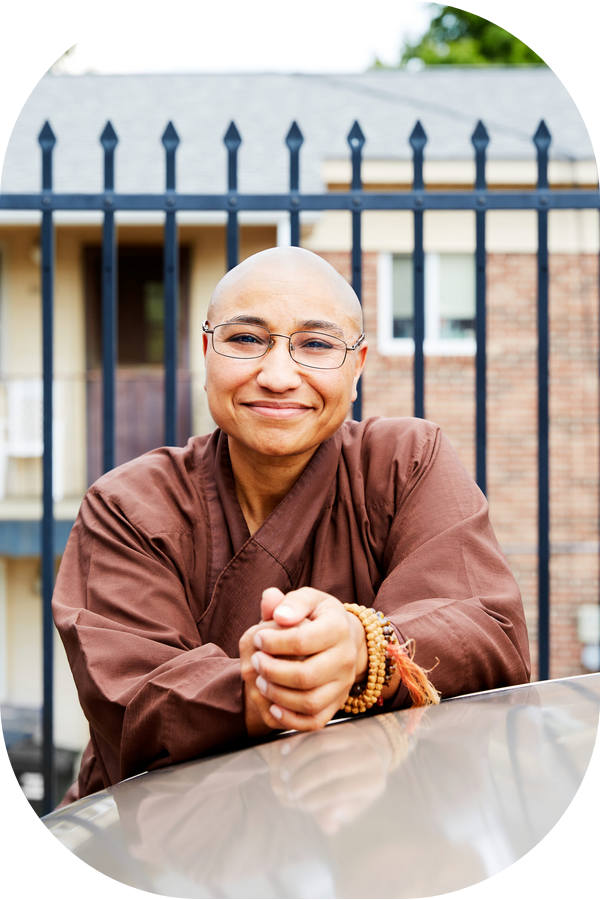

Yet, the question of hope is a human one, so it arises again and again. It cannot go unanswered. I consulted the teachings of several Buddhist teachers; the term, “wise hope” arose. I most especially appreciated these words from Sister Clear Grace, who was ordained in the Plum Village/Thich Nhat Hanh tradition of Zen Buddhism:

wise hope can allow us to see things as they are—that nothing is inherently permanent or fixed. The Buddha directs us to a path that is wishless or without expectation. It is from this very space that we are then able to create and be the very hope that we wish to see.

So, where common hope might not be skillful, one can cultivate wise hope. Not easy, but possible. With practice.

Hope as Action in Community

In her influential book, Hope in the Dark: Untold Stories, Wild Possibilities, published first in 2004 (yes, twenty years ago) Solnit offered this image of hope:

I say all this to you because hope is not like a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. I say this because hope is an ax you break down doors with in an emergency; because hope should show you out the door, because it will take everything you have to steer the future away from endless war, from the annihilation of the earth’s treasures and the grinding down of the poor and marginal. Hope just means another world might be possible, not promised, not guaranteed. Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope.

That commitment to hope as action continues to inform Solnit’s writing. In fact, in that quote I shared in the first half of this sermon, she closes by pointing us towards action. Hear it now in full:

Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists adopt the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting.

That’s what I said before. And then she concludes

It is the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterwards either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone.

Most actions, to be effective, need repetition and refinement. Therefore, if hope is an action, it is in need of practice. Cultivating hope can be viewed as a spiritual practice – one rooted in trust more than certainty. A practice one engages in over and over, not out of habit, not out of guarantee of an outcome, not out of certainty, but out of commitment and intention.

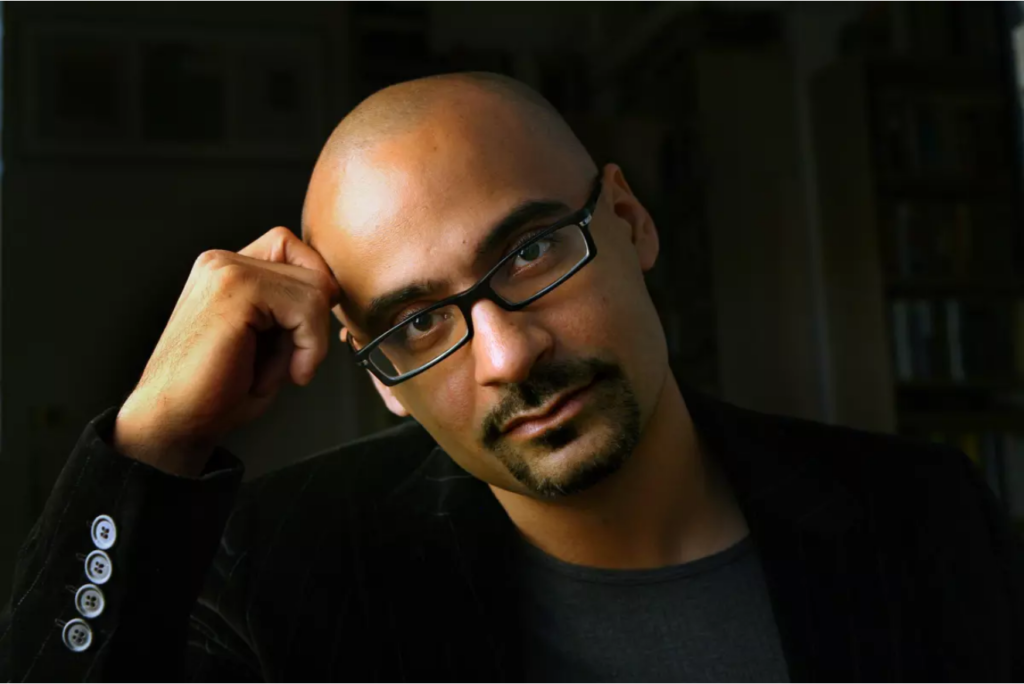

After the 2016 presidential election, the writer, Junot Diaz wrote a note to his sister, who was despairing of the future. Published in the New Yorker magazine, he distinguished between common hope and “radical hope:”

Radical hope is not so much something you have but something you practice; it demands flexibility, openness, and … “imaginative excellence.” Radical hope is our best weapon against despair, even when despair seems justifiable; it makes the survival of the end of your world possible. Only radical hope could have imagined people like us into existence. And I believe that it will help us create a better, more loving future.

The thing I love about the concept of practice is that it does not require having hope now. We can “fake it ‘til we make it” (a wonderful strategy of twelve step spirituality). We can trust that others have a sense of hope or sense of agency on those days when we do not; and that we can and will lend our sense of hope (or agency) on the days we have it, and others do not.

Hope is not an action or series of actions of an isolated person: the lone Sisyphus pushing a boulder up a hill. Hope is a series of actions attempted in community, among others, practiced and returned to, again and again, with no sense of perfection or completion.

No hope in the results, no knowing if it will make a difference, but by the very act of determined and wise action, in community, we express and experience love – love of others, of being loved.

I have shared so many quotes with you in this sermon. It may be hard to keep track. I’m going to return to the one from Thomas Merton, sharing it with you now in whole, because I want you to know how it ends. I want you to feel how hope is love and love is hope.

Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect.

And then he continues

As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. You gradually struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people.

And then he concludes

In the end, it is the reality of personal relationship that saves everything.

I appreciated your sermon on hope at the time but I knew I needed to also read it. Thank you for posting. This will take additional reads. I admit my “hope” had taken a hit with this election which forces me to look deeper at so many other issues that need more attention. My trust in so many things is damaged.

Have you read Ethan Trapper’s book “How to Love a Forest: The Bittersweet Work of Tending a Changing World”? It shows much hope and in the context of a forest – years to see success, even impact. Hard to accept a slow timeline at my age of 73.

Enough from me.

Holly, I’m so glad that the sermon has been a good companion and that posting it here has been helpful. I have wondered about Ethan’s book, but haven’t read it yet. Thanks for the suggestion. I have thoughts about that second to last sentence – how our own sense of mortality is impacted by our genuine experience of interdependence – of knowing the truth of it beyond intellect, trusting that nothing worth doing will ever be completed in our lifetimes, yet our part still hold meaning and purpose because we are present in the future, even if our life in this form is done.