So be it. See to it.

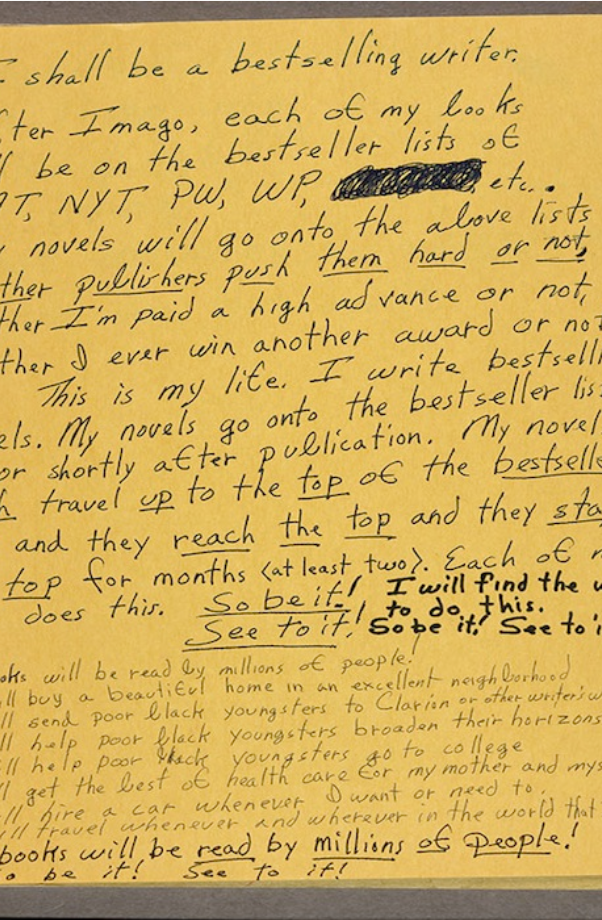

This is how I end most of my sermons. It is a phrase that the late author, Octavia E. Butler, used at the end of one of her personal affirmation journal entries, naming her aspiration to become a bestselling writer.

I find it describes the core of one of my theologies and spiritual practices so much, I made a tattoo of it on the wrist of my dominant hand, not long after you called me as your minister.

So be it: practice radical acceptance; know you do not control everything, and sometimes nothing. See to it: change can be cultivated; shape it; remember your agency.

The original title of today’s service was To Be Determined. A month ago, when I wrote the blurb, I wasn’t sure we would know today what the outcome of the election would be. Hell, on Tuesday evening (early), I didn’t think we’d know for days. To Be Determined seemed both clever and apropos.

Let it be noted that I am officially retitling the service: So be it. See to it.

The morning after the election, staff and lay leaders got together and we planned, then that evening held, a post-election vigil that began with these words from my mentor, the Reverend Peggy Clarke.

We do not need to turn to joy, yet.

We do not need to find hope, yet.

We do not need to organize, yet.

Today, we can howl at the moon,

Cover our mirrors,

Rend our garments.

There will be time to reignite,

To fight for our country,

To protect the vulnerable

With everything we have.

But, today,

We grieve.

You may well be in that emotional space – lamentation, grief, confusion. Perhaps shocked, but not surprised (as so many of BIPOC neighbors and friends find themselves). If so, I honor that. We honor that. Each of us will have our own timelines about how we move through whatever difficult emotional landscape we may be experiencing, the one that is related to political outcomes, but at its root and source, is about values and morals and ethics and justice; is about how the embodiment of love at the center just got a whole helluvalot harder to make real for more people.

And today’s sermon, while holding that space, while holding you, begins the process of opening into a “what’s next?” space. If you aren’t ready for it, I hope you will stay and let it wash over you, receiving gently what touches you, while releasing the rest – any sharp shoulds or mean musts.

Daniel Hunter is creator of the Choose Your Own Adventure website I preached on in August: whatiftrumpwins.org. He published a thing on Nov 4th – yes, the day BEFORE the election, on how to be in a world in which Trump won the presidency. It is a list – these folks who advise us on how to resist fascism, they love their lists! Before launching into the first on the list, Hunter says this, which took my breath away:

for us to be of any use in a Trump world, we have to pay grave attention to our inner states, so we don’t perpetuate the autocrat’s goals of fear, isolation, exhaustion or constant disorientation.

His list starts with trust yourself, and then goes to find others whom you can trust. That’s one and two. We can groove with that. Number Three is grieve:

If you aren’t a feelings person, let me say it this way: The inability to grieve is a strategic error. After Donald Trump won in 2016, we all saw colleagues who never grieved. They didn’t look into their feelings and the future — and as a result they remained in shock. For years they kept saying, “I can’t believe he’s doing that…”

Believe it. Believe it now. Grief is the pathway to acceptance.

I don’t want this sermon to be a list, but Hunter’s list is so darn good, I don’t not want to tell you. Number Four is releasing that which we cannot change. Like all the pardons that will come on Day One. Much less what will happen on Day Two.

Hunter warns against two things – symbolic actions (I’m not fully in agreement with hina bout that) and public angsting. About that latter, he offered examples, such as posting outrage on social media, or talking with friends, or sharing and amplifying awful news. He advises against this because ultimately, instead of being informative (and thus constructive), the impact ends up being demoralizing and thus, hurts our capacity for action.

Overall, it’s a list of ten and so far, I’ve shared four. I won’t share the second half – perhaps one of you could create a study group about it? But I do want to name Number Five, because it’s what I decided is one of the many important messages I could bring you today. Hunter names it “Find Your Path.”

You’ve likely heard at least one of these quotes, a different approach to the same advice of find your path. There’s this one from Teddy Roosevelt:

“Do what you can, with what you have, where you are”

The late 20th & 21st century Christian theologian, Frederick Buechner, said it this way:

“The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

Or the Talmud says something like this:

“Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Act justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly, now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.”

I want to talk with you about Your Path. I want to remind you, gently or forcefully, that you and your inherent worth and dignity matter and your presence in the (phrases from child dedication) ~ all of you is necessary, especially when you remember, you don’t have to do it all.

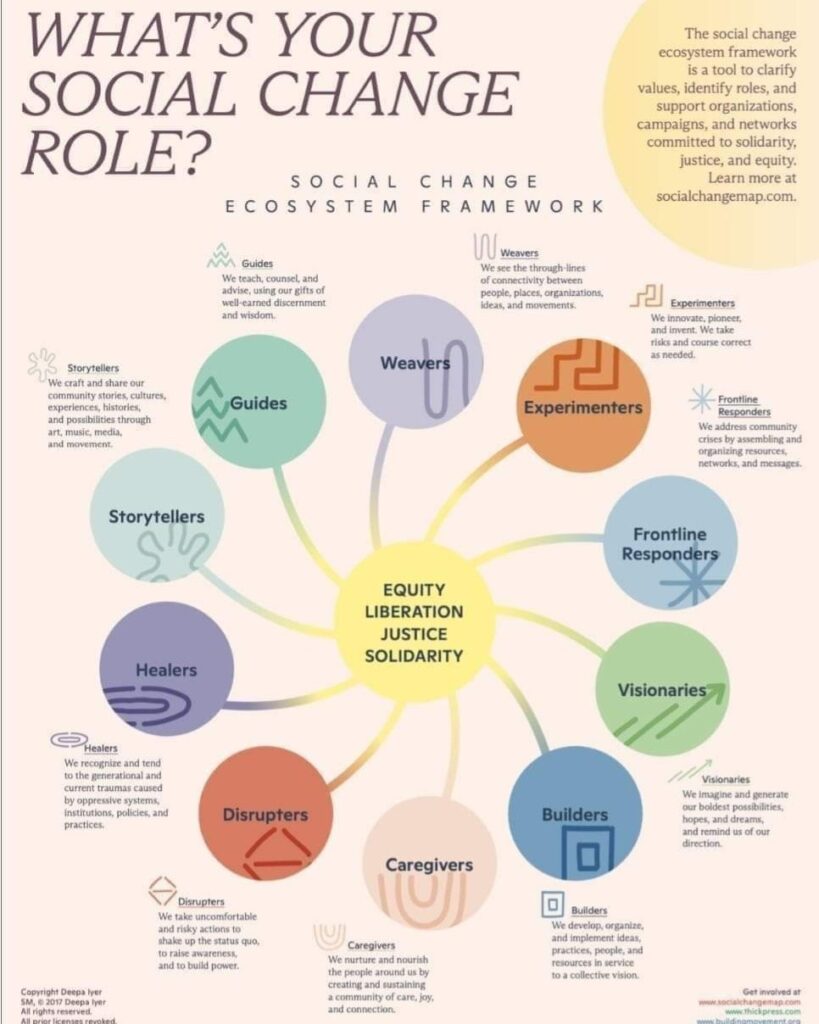

And deepening this message, I want to introduce you to the work of Deepa Iyer as a way that we each and we all might find our paths, or if we already know them, befriend and honor them. Deepa Iyer is a South Asian American writer, strategist, and lawyer, whose work is rooted in Asian American, South Asian, Muslim, and Arab communities. While she has many gems to offer us, today I want to introduce into our shared congregational parlance something that is sort of another helpful list, but really, the options are presented as an eco-system. A social change eco-system framework, which she first published in 2017.

In this framework, Iyer offers that there are (at least) ten roles that exist in organizations, campaigns, and networks committed to solidarity, justice, and equity. As I read through the list once, I invite you to listen for the role that resonates with who you understand yourself to be and maybe, who you aspire to become:

Guides: who teach, counsel, and advise, using gifts of well-earned discernment and wisdom.

Storytellers: who craft and share community stories, cultures, experiences, histories, and possibilities through art, music, media, and movement.

Healers: who recognize and tend to the generational and current traumas caused by oppressive systems, institutions, policies, and practices.

Disrupters: who take uncomfortable and risky actions to shake up the status quo to raise awareness and to build power.

Visionaries: who imagine and generate our boldest possibilities, hopes, and dreams and remind us of our direction.

Caregivers: who nurture and nourish the people around us by creating and sustaining a community of care, joy, and connection.

Builders: who develop, organize, and implement ideas, practices, people, and resources in service to a collective vision.

Weavers: who see the through-lines of connectivity between people, places, organizations, ideas, and movements

Experimenters: who Innovate, pioneer, and invent, as well as take risks and course correct as needed.

Frontline Responders: who address community crises by assembling and organizing resources, networks, and messages.

We exist in a social change eco-system – an interdependent web of social change existence, one might call it – and we can find where our deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet. Not all of us are frontline responders, but some of us are. Not all of us are experimenters, but we can appreciate and be thankful that some of us are willing to innovate, pioneer, and invent on behalf of the whole. Some of us are Caregivers and some of us are Builders and some of us are Disruptors. It is up to us to see to it that we engage those gifts and offer them to the world, our community, each other. It is up us to see to it that we all do our part embodying “the vast conspiracy to heal our common life.”

Not only do we need to learn, or be reminded, of who we are, and what we can do (and can’t do), I believe that now and in the coming weeks and months, we need to double down on our touchstones: on our spiritual practices and on our integration of what Unitarian Universalism means in our lived lives and how we bring it beyond these walls.

Towards that end, I want to inform you, perhaps for the first time, or remind you, perhaps for the umpteenth time, about the origin story of our flaming chalice. There is power in knowing and remembering why it is we light that flame each Sunday; why it is such a meaningful symbol, shared nearly universally, among Unitarian Universalists. So here is my summary of the origin story of our flaming chalice, based on the work by my seminary professor, the Reverend Mark Harris, from his book, The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism.

The formal association with our faith movement emerged during World War II when the nascent Unitarian Service Committee (now the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee) adopted it as their symbol while, in 1940, they were assisting refugees in Eastern Europe who were escaping Nazi persecution. As we tell the story in our New UU class here at First UU, Hans Deutsch – an Austrian who had escaped to Paris – encountered the executive director of the USC, the Reverend Charles Joy, who asked Deutsch to create a symbol. Deutsch did so, using familiar elements open to interpretation across an array of religious or cultural backgrounds. “The USC adopted it for a seal for papers, an emblem on vehicles, and a badge for agents moving refugees to freedom.”

When Unitarians and Universalists came together in 1961, a version of the flaming chalice was paired with two intertwined circles, representing each of the two heretical, once-Christian denominations coming together as a new religion. Over the years, beginning in the 1980s, a majority of congregations adopted the chalice as a focal point of worship services. Yet, there is a much older, indirect historic origin story that is told less often.

In the 15th century – before the full out Protestant Reformation to which we can trace our religion’s roots – there was a Czech priest named Jan Hus who was ultimately burned at the stake, in 1415, for heresies, including – and most relevant to us – sharing the communion cup with lay people. In doing so, he conveyed that all people – including clergy and lay folx – are equal. Supposedly, while being burned at the stake, he prophesied that in cooking a skinny goose, from the ashes will arise a swan which cannot be burned. In Bohemia and Eastern Europe, a great movement began, using the flaming chalice as their symbol – they were called the Hussites and in 1433, they forced the church to give the communion chalice to all the people, not keeping it reserved just for the priesthood. This movement strongly influenced the Polish Brethren, to whom we can trace our Unitarian roots.

Our flaming chalice is a signal of light in times of dark shadow; a beacon of hope in hard times; and a symbol of resistance. In that spirit, I have an invitation for you: next Sunday, after the fire drill (yes, the fire drill at the end of the service), I hope you will stay for our noon-time screening of the Ken Burns documentary, Defying the Nazis: The Sharps War, which is the story of our Unitarian Universalist ancestors – in particular, Waitstill and Martha Sharp – who went to Czechoslovakia and help hundreds escape Nazi persecution. Whether you saw the film when it came out in 2016, or haven’t seen it yet, now is a good time to connect with this touchstone of our faith: there have always been heroes among us, though not without a cost.

In closing, I want to share this message, shared with tens of thousands of Unitarian Universalists on November 7. It’s from the Unitarian Universalist Association and I bring it to you so that we UUs here in Burlington, Vermont, resonate with UUs throughout the nation and the world, remembering that we are not alone:

Beloveds, we will hold our fear together.

We will honor our rage and devastation and grief.

We will hold one another ferociously, tenderly, faithfully.

And then:

We will move deliberately.

We will invest in trust.

We will claim joy, rest, and sustenance.

We will resist en masse.

We will fight fascism and continue the struggle for democracy.

We will continue to build our movements for justice.

We will focus our efforts and abandon distractions.

We will create safe harbor for those in danger.

We will leverage our resources.

We will sharpen our skills and our analysis.

We will act as if no person is disposable.

We will refuse the politics of division and despair.

We will seek the wisdom of elders and of history.

We will weave deeper connections with our neighbors.

We will fight for our survival.

And we will create the conditions of possibility for our thriving and liberation.

Let us be, like the babies we dedicated this morning, part of the vast conspiracy to heal our common life.