First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

November 24, 2024

For reasons I can’t explain or rationalize, about which I am vaguely embarrassed (and thus, why not share with you all here and now) I have been re-watching a television show from the first decade of the century, one my children and I watched together. I raised them without commercial television, but we would rent or purchase dvds of shows, watching whole series like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Lost. And of course, it all started with Star Trek: TNG.

In the days before the Election and in the days since, I have been watching the show, Heroes. Do you know it? It’s about ordinary people discovering they have special powers – becoming invisible, reading minds, melting objects, spontaneous regeneration, painting the future – the list seems endless. And while the title of the show is Heroes, not everyone with special powers is a hero. In fact, most of the heroes, at one point or another, you can’t quite tell whether they are a villain or a hero. And some are both. A few, at least in the first season (that’s really only as far as I’ve gotten), seem to be purely good or purely evil. But if my recollection is correct, I think over the many seasons of the show, even that changes. It turns out that the line between good and evil isn’t to be found in one group versus another, but within the heart of each human being, living out our ordinary and complex lives.

As I reflect on it more, I guess it’s not surprising that I am drawn to stories about heroes and the repeating narrative of everything seeming to be lost, and then saved at the last moment and in unexpected, perhaps even miraculous, ways. I guess it’s not all that surprising that, given the heartache I am feeling for our nation, I long for such a story.

The more surprising thing is that I am satisfying this longing by watching a rather dated show that is absurdly unrealistic, has acting that is pretty mediocre and dialogue that is definitely not stellar. I suppose we can’t always change what the heart longs for.

All of which is to say, I want to tell you a bit more about our hero, whose story I began in our Time For All Ages: Lydia Maria Child.

Before setting out with her husband on that rather absurd, idealistic project to undermine the slavery-saturated sugar economy, eight years earlier, Maria had written in 1833 a book called An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans. While at the time, some supported gradual emancipation, and others supported the repatriation of Africans back to Africa (hence, the founding of Liberia), Maria supported the immediate emancipation of enslaved peoples in America and is thought to be the first white American woman to do so in print. (So says The Smithsonian.) In her tome, she criticized not just the slave-holding South, but also the Northern businesses that profited from trades directly implicated in industries dependent upon the enslavement of human beings.

While she had experienced widespread popularity and economic success from having published The Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy four years earlier, the public was not ready to accept her extreme views. For several years, she experienced a deep decline in the sales of all her books and pamphlets. Some publishers refused new works she sought to make available. She even lost a job. In the introduction to the text, she anticipated this possibility:

“I am fully aware of the unpopularity of the task I have undertaken, but though I expect ridicule and censure, it is not in my nature to fear them.”

Yet, this decline did not last her whole career. Or in the scheme of things, for very long at all. And it’s interesting to note, The Frugal Housewife has – so far – seen 33 printings. And An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans? Well, just last year, the University of Massachusetts re-issued a new edition.

Like First UU’s own minister at that time, Rev. Joshua Young, whose spirit I consider responsible for drawing me to this congregation, Maria held John Brown in high regard. She found Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry to stir within her a “renewed earnestness to the righteous cause for which he died so bravely.” She wrote to Brown while he awaited execution, praising his courage and offering to come and nurse his wounds. She wrote to Governor Henry Wise of Virginia, seeking permission to nurse John Brown. The Governor responded by condemning Brown’s action. When the correspondence was published in the New York Tribune, Maria received a flood of congratulations from the North and condemnation from the South.

How delighted I was, in doing the research for this history sermon, that I learned that the same person who gave the eulogy at John Brown’s funeral, the funeral that our Rev. Joshua Young officiated, abolitionist Wendell Phillips, gave the eulogy at Maria’s funeral as well. There are only so many degrees of separation, it seems, even if Kevin Bacon is not involved (that’s a GenX reference, for those of you who did not get it).

When I think of our UU Value of Pluralism, we can find a direct thread to many minds of her day, including Maria’s. She published a three-volume work, The Progress of Religious Ideas through Successive Ages in 1854. This interest deepened for her over her lifetime. When a group of Unitarians founded the Free Religious Association in 1867, she found agreement with their perspective. She attended regularly, and after her husband died, even more frequently. In 1878 she published her own “eclectic Bible” of quotations from the world’s religions, Aspirations of the World, naming as her motive, “to do all I can to enlarge and strengthen the hand of human brotherhood [sic].”

A side note: if you have taken a New UU class with me, you know that I am not a big fan of Unitarian Universalism overclaiming famous people. Such as saying that Thomas Jefferson was a Unitarian (he wasn’t).

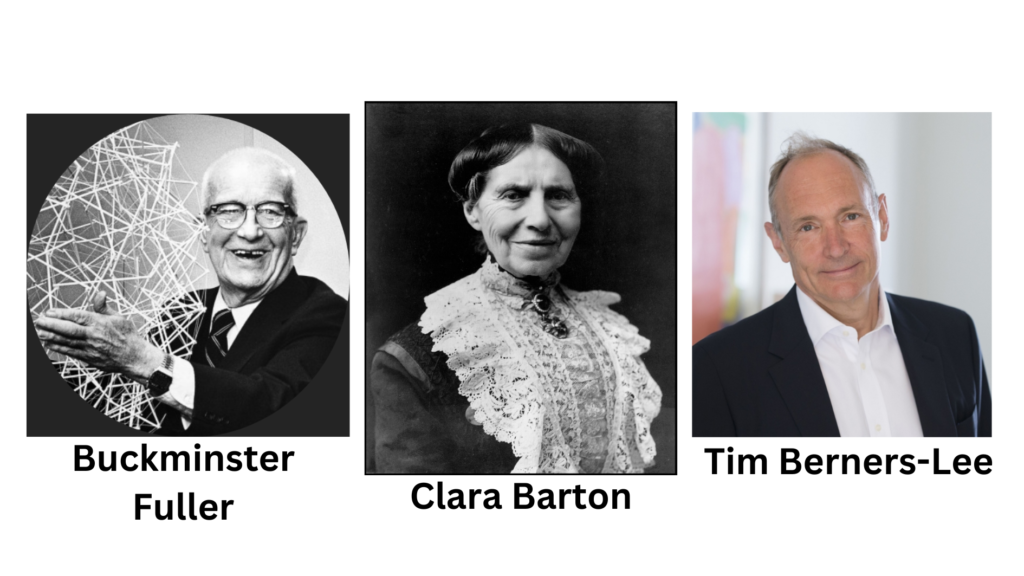

There are plenty of famous UUs: Buckminster Fuller. Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross. Tim Berners-Lee, who can more reasonably claim to have invented the world wide web, more so than Al Gore: Tim is a UU.

So I feel it’s only right that I acknowledge that while Lydia Maria Child was clearly Unitarian, she was pretty ambivalent about Unitarianism. At the age of 20, she was baptized at a church that 3 years later declared itself Unitarian – it was at this baptism that she chose to be called the name, Maria, rather than her given name of Lydia.

Her beloved older brother became a Unitarian minister and when she lived with him, which was for an extended period, she attended church with him.

She hung out with lots of influential Unitarians; she was influenced by them, and in turn, they were influenced by her. It’s believed that she played a pivotal role in turning William Ellery Channing toward an abolitionist stance. And…

…well, she didn’t really have a whole lot of respect for Unitarianism and some gathered Unitarians. According to the online Unitarian Universalist Dictionary of Biography, she said the following about Unitarianism: it is

“a mere half-way house, where spiritual travelers find themselves well accommodated for the night, but where they grow weary of spending the day.”

I’m not even sure what that means, but I can tell she is throwing some shade there. At another time, she wrote of her experience in New York City, “The Unitarian meetings here chill me with their cold intellectual respectability.”

In those two years when she lived in the same village I would later raise my children, she thought the Unitarians in nearby Northampton (which was my home congregation where I raised my kiddos) were too moderate, too self-important, and not worth her while.

That said, she joined with Unitarians who founded the Free Religious Association, a bunch of radical free thinkers, who are the same ilk who founded the congregation in Florence, a congregation that would later merge with the more staid Unitarians in Northampton.

Quite an extraordinary life of an ordinary person.

In closing, I share these words from the late historian, Howard Zinn, which will likely also have a cameo in my sermon on December 8th, which is about different flavors of hope. I choose these words because in them, I hear the echo of Lydia Maria Child and her presence in the world:

May we be a people who believe ourselves to be ordinary, yet find ourselves with super powers to make the world a better place.

Let us join small groups of determined people who do not give up during the first, second or hundredth gale.

Let us lend our values and our hopes to a future made of an infinite succession of presents, in defiance of all that is bad around us.

Let us be a people who recognize that our heartache is holy – and then, let us be moved to action by the very fact of it.

Let us risk the absurd – for it may not bring an end to all injustice, but may add to the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction.