April 28, 2024

First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

Before I attended, I had read the synopsis for the musical, thinking it might be helpful, like anytime I go see Shakespeare. So I knew it would end tragically.

I feel the need to warn you, especially since the Flynn announced last week that the Broadway show, Hadestown, is coming to Burlington in October: this sermon contains spoilers for that musical.

Now, I don’t feel badly about this, because the show is based on an ancient Greek myth that has been around for a very long time, …

And still, the music and the acting and the set and the theatrics of it all, the energy and music vibrating in my body and throughout the audience, the hope of collective liberation that rose up as the narrative reached a crescendo ~ all that enthralled so much that when the ending came, I could not believe it.

I could not believe that the lovers were permanently and irrevocably separated. I was devastated. It did not matter that I knew it ahead of time. It did not matter that it was a story being told on stage. I was suffering along with the characters.

I sat in my seat, tears streaming down my cheek. I thought if I was still enough, disbelieving enough, a surprise ending would appear, perhaps stage left, saving me from despondency.

Such things happen often in Hollywood and sometimes on Broadway, but it did not happen. Orpheus looked back, and in so doing, consigned his beloved Eurydice to live in hell for eternity.

This is not what I wanted for Orpheus and Eurydice.

It is not what I want for me. Or for you. It is not what I want for the generations to come. It is not what I want for any creature, near or far, known or unknown. It is not what I want for this magnificent planet.

Back in the theater, realizing the playwright was staying true to the myth (which I respect), I held my breath. I waited. And I wanted. Oh, did I want a different ending.

Then I remembered to breathe. And I did so, in and out. It was then that I could watch my wanting. It was then I observed my longing for something different than what was. It was then that the tragedy was still WITH me, but it was no longer IN me.

Then the narrator, Hermes, confirmed for the whole audience:

It’s a sad song. It’s a sad tale. It’s a tragedy. It’s a sad song. But we sing it anyway. ‘Cause here’s the thing: to know how it ends and still begin to sing it again.

What are we to do with tragedy? With suffering?

Are we to walk up a daunting number of nearly impossible stairs spiraling along a sheer-sided volcanic plug on tiled steps that are wet with rain, monkey pee and poo? Only to realize once we reach the top, the only way down is back the same way?

Are we to keep living in a world on fire in these mortal bodies that give so much, but also take so much from us, of us? This mortal life is full of tragedy and suffering, though some of us may call it by a different name.

We just might call it muck.

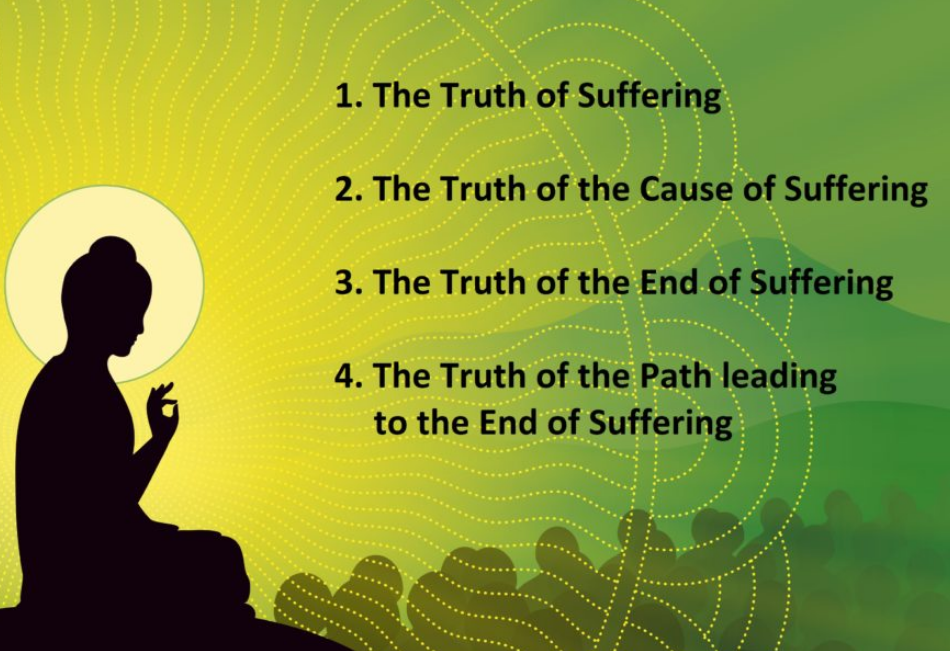

I have heard some people who are unfamiliar with Buddhism, or familiar in only a cursory way, say this coarse generalization: that Buddhism “believes” that life is suffering, like there’s an “amen” at the end of that statement. If this were the case, it would be such a downer, so they want to keep their distance, because, well, that’s such a downer.

In fact, Buddhism does begin with Buddha’s statement that life is suffering. But that is just ONE of the Four Noble truths. Starting and stopping there is like starting and stopping with the first of the Twelve Steps – admit you have a problem and that life has become unmanageable – and call it done. In the world of recovery, there are eleven more steps.

And in Buddhism, there are three more Noble Truths:

Yes, the first is that life is suffering. In Pali, the word is “dukkah.”(which sounds alot like monkey poo)

The Second Noble Truth names the CAUSE of dukkah, of suffering.

The Third Noble Truth, having named what causes suffering, proclaims that suffering can cease.

And the Fourth Noble Truth is the path to bring that suffering to an end.

This is a good reminder that it can be problematic to think you know everything, when you know things only in part.

Suffering IS a big word. It’s intimidating. It’s heavy. It’s…a downer. Not to mention there are theologies out there that pair suffering with redemption in a way that is highly problematic. There are good reasons to give it a wide berth.

So, what if we agree on a different word? What if we were to say that all of us encounter muck in our lives?

Sometimes it’s personal. Sometimes it’s interpersonal. Sometimes its source is random and sometimes it is intended and cruel. Sometimes it comes from systemic oppression, adding both acute challenges and chronic layers of barrier, external and internal.

How do we make the most of muck? Especially since it is April in Vermont – mud season. Especially since our Earth Teacher this past month has been…yes…mud.

The late Buddhist monk, the wise teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, tells us that without mud, there is no lotus. Without the very smelly mud, there is no fragrant, beautiful flower. That the path of transforming suffering is possible and is within us, accessible through the practice of mindfulness.

It’s that breath that allows just enough space for us to know that there is suffering, but it is not the defining aspect of ourselves.

It’s that breath that allows us to know that suffering is temporary ~ that it gives way to joy, or to a neutral state. Just as joy gives way, and neutral states give way. It’s the sad song of our mortal lives.

It’s that breath that allows us to see that suffering and happiness are not polar opposites, but woven of the same cloth.

Like the mud gives way to the lotus that eventually withers and returns to the mud, Thich Nhat Hanh says that suffering and happiness do not exist one without the other and are in constant flux of being. He said “happiness and suffering are not enemies. They inter-are.”

The possibility of transforming our relationship to suffering comes not from the fact of mindfulnessbut from practicing mindfulness. Over time. Usually over long periods of time.

In her essay, “Of Mud and Broken Windows,” Michele MacDonald-Smith writes

“I have been practicing Buddhist meditation or twenty-one years, and this journey reminds me of how long it takes a tree to grow, bear fruit, and reach maturity. My family and I planted a mango tree together twelve years ago in Honolulu. It grew slowly the first five or six years. Then it started growing very quickly. It grew quite tall, but it didn’t flower. Two years ago, it flowered but we had no fruit. Last year, we had baby mangoes and we were so excited, but they didn’t mature. It takes time for the tree to grow strong enough to bear fruit, and to hold the fruit to maturity. This year, we had twelve delicious golden mangoes.”

Out of mud comes the lotus. Out of soil comes golden mangoes but only over time.

At this point, I feel it’s important to say a couple of things about the nature of suffering. This sermon is not suggesting that if it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger. I am not a pastor who will ever tell you that everything happens for a reason. There is some suffering that is too much suffering. Too much in length. Too much in depth. Too much cruelty. If you have experienced this, I am sorry that happened to you. You did not deserve it.

I also want to say that acceptance of the fact of suffering, choosing to embrace it rather than resist it, is not approval of the pain or its source. Approval or consent are quite different from mindful acceptance.

Suffering is not a good thing. But it IS a thing.

And when we try to deny any reality, to come up with alternate facts, that effort leads to spiritual bypassing, dysfunction, chaos, and in some cases, creates fertile ground for the rise of fascism.

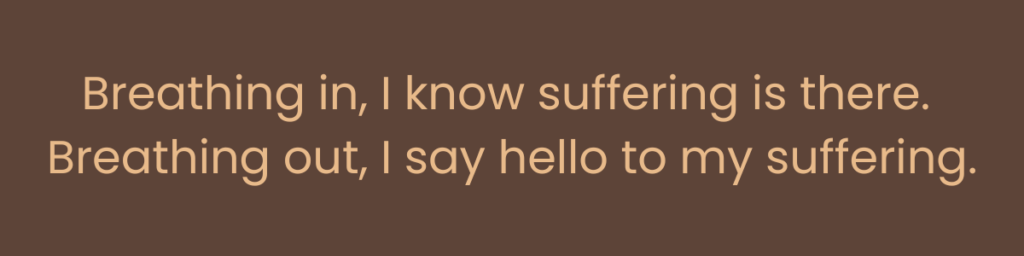

What could the mindful embrace of suffering look like in our lives? Thich Nhat Hanh encourages speaking these words:

As I say it again, listen to possibility in these simple words:

For those of you, either at home or here in the sanctuary, if you would like to join me, I’ll say it once again. For those who do not want to join in, that is well and good too – you bring your listening and witnessing, which strengthens us all:

Thich Nhat Hanh says that when a parent hears a baby crying, the natural thing to do is to take the child into their arms – not suppressing or judging or ignoring the crying, but cradling the baby with utter tenderness. Mindfulness, he says, is like that parent embracing suffering without judgment. Like the person who says,

“Hello, my suffering, I know you are there.” or

“Good morning, my pain, my sorrow, my fear. I see you. I am here. Don’t worry.”

[these phrases both come from Thich Nhat Hanh]

Or perhaps,

I like to think this works not only for individuals, as I have said, but for ever larger groupings of people. For couples, bringing intentionality to their relationship. For families going through a rough patch, who do not let the rough patch become their narrative of who they are.

Even for congregations going through challenges, such as budget worries or significant staff transitions. Or having an association with someone who commits a hateful act of violence.

And I think it’s at play when folks who experience systemic oppressions refuse to give up the right to joy; insist on full access to a fulfilling life; proclaim the necessity of rest.

I think it is here that I want to share a quote from the book, No Mud, No Lotus. It’s about how we all need each other, at one time or another, or perhaps all the time, to get through the muck of our lives. Thich Nhat Hanh wrote,

There are times when a case of suffering is so great, it needs recognition from more than just one person. We all need help sometimes when suffering threatens to overwhelm us. We can borrow the collective energy of mindfulness of a group of practitioners, in order to recognize and embrace the block of suffering in us. When suffering has become a seemingly impenetrable obstacle, we can learn how to draw on the support of others.

source: No Mud, No Lotus

As we move towards closing, I want to tell you about this stole, which is made of cloth from a weaving studio on Inle Lake in Myanmar. It is made of both traditional silk from silk worms and silk made from the fibers within the stem of a lotus. It is not an ancient industry in that part of the world – it was developed sometime mid-20th century. It is painstaking and time-consuming to produce.

I have come to think of the alternating warp and weft as a reminder of how suffering and happiness are woven of the same cloth, that muck and magnificence co-exist.

Let us see if we can live into the wise Buddhist teaching that “the art of happiness is also the art of suffering well.”

Let us begin to sing again, even if it is a tragedy. Even if we know how it ends.

As we move through the mud and muck of our lives, should any of us find ourselves with bare feet moving in the midst of decidedly unpleasant matter, may there be a beautiful temple or a fragrant lotus awaiting us, even if it is only eventually and the way there seems far and daunting.

May we have with us, whether in joy or in suffering, good companions to hold us up and upon whom we can lean.