First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

December 3, 2023

Part I

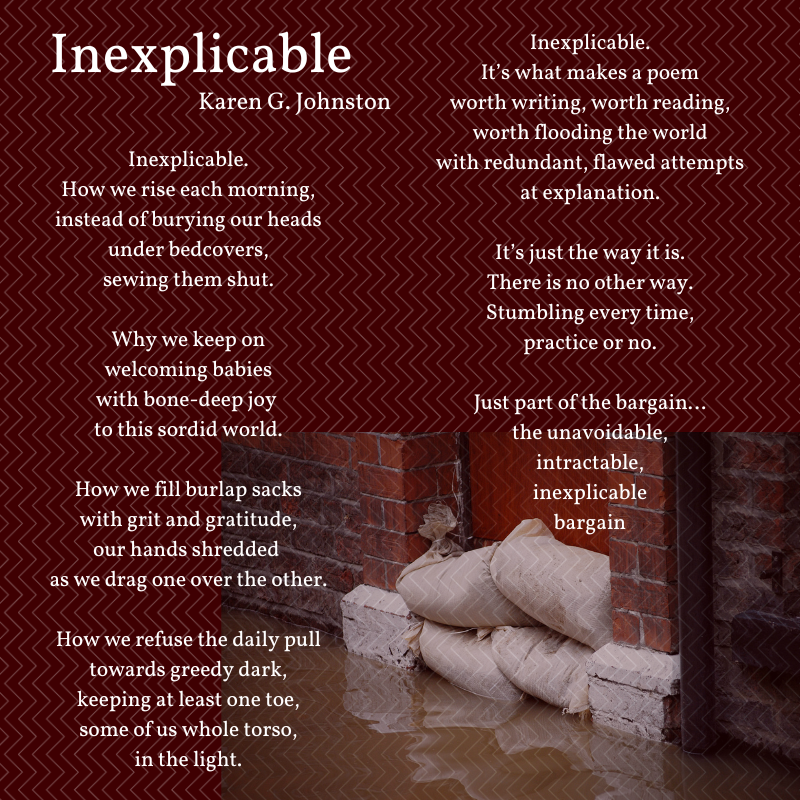

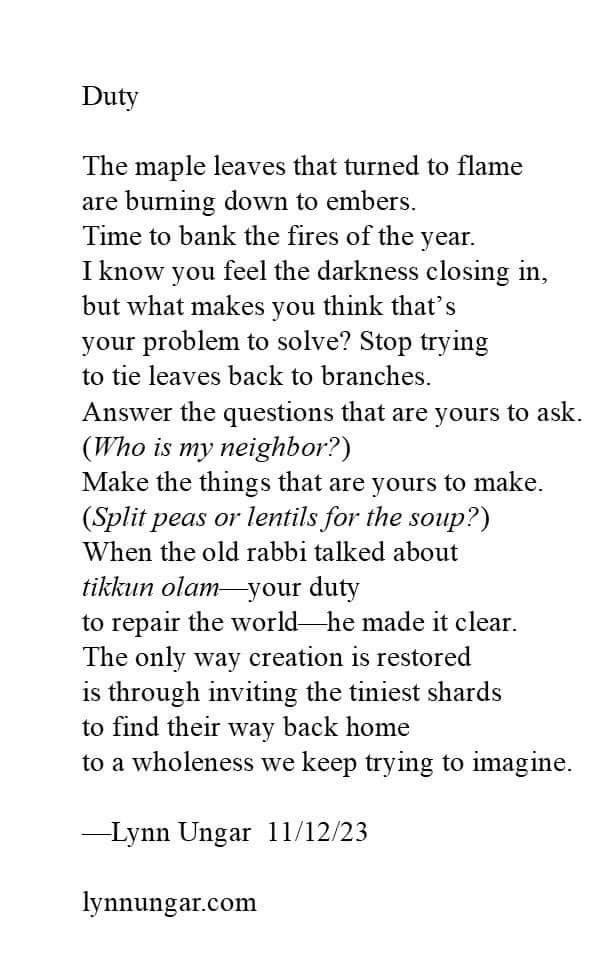

To begin, a poem, titled “Duty” by Unitarian Universalist minister and poet, Rev. Lynn Ungar:

I want to invite one line to take up residence in my heart. In your heart. In our collective heart. This one:

Stop trying to tie leaves back to branches.

Just over a week ago, we came to know the horrific news of the shooting of Tahseen Ali Ahmad, Hisham Awartani, and Kinnan Abdalhamid here in Burlington.

Six days ago, we learned that the suspected shooter was someone who had spent part of the summer and fall as part of our congregation.

This is shocking. Dear Ones: we are in shock. Though we are not at the center of this act of violence and its damage, we are very much in its wake. We must not fool ourselves into thinking otherwise. We must recognize that much was damaged when that gun was fired, and that includes how we make sense of the world.

Part of that shock looks like traveling to the Land of What-If. For some, the Land of What-If is filled with heightened worries about whether we are safe gathering in this building: what if he had brought the violence here? For others, the Land of What-If is filled with self-doubt, sometimes mixed with blame: what if I had foreseen the violence and could have stopped it?

We have neighbors and friends who are struggling with how this act of violence, which looks like a hate crime, could happen here in this liberal, welcoming bastion. Some of us are struggling with that, too. They are traveling not in the Land of What-If, but in the Country of How Could This Happen?

We have our own travels in that country: how could it be that a Unitarian Universalist perpetrated this kind of violence. In fact, I got an email recently in which someone said that if he did it, he couldn’t be a real Unitarian. It’s simpler, less painful, to cut him out of our family of values, then to contemplate the other possibility.

The more we are unwilling to at least consider and come into reckoning with, the weightier those questions become in our subconscious and in our own community. We Unitarian Universalists can sometimes fall prey to a sense of Exceptionalism – that we are somehow outside the pernicious influences that other human beings are vulnerable to. Yet we are human. Yet we are a part of the interdependent web of all existence and it influences us. This act of violence raises painful questions. And so we ask, how could this happen?

And of course, closer to home, how could someone – known to our congregation; someone who volunteered in one of our vibrant, caring ministries; someone who sat in these pews – how could someone from within not the wider Unitarian Universalism do this, but how could someone from among us do this?

These are very hard questions to even allow to bubble up, much less answer. And when there are no sure answers, when uncertainty is what is on offer, we loved-and-loveable-yet-flawed humans, can take it out on each other, or ourselves, because that is somehow easier to do than sit with the unknowing and the discomfort that some things do not make any sense. It’s like we are trying to tie the leaves back on the tree, rather than wait for them to grow back through the natural cycles of growth and healing.

I want to caution us about a particular way of meaning-making that we might lean towards. By which, I mean, that we try to explain what happened by attributing this act of violence to mental illness. There are several reasons I want to caution us about this.

The first one is: there are plenty of people who experience mental illness who do not attempt to murder others. It is not fair to the many of us who experience one form of mental illness or another to have that suggested or inferred that this explains this violent act.

Secondly, as a congregation that has adopted the 8th Principle, committed to dismantle systems of oppression, including racism, in ourselves and in our institutions, I think it is of the utmost importance that we not fall into the pattern in American society that names violent persons of color as terrorists or thugs while calling white perpetrators of violence “mentally ill.” This is especially important since we are a congregation that is predominantly white. This is especially important since this act of violence was perpetrated against an ethnically-marginalized group. This is especially important since our congregation’s association with the shooter may become part of the news cycle – and for us to lean on the explanation of mental illness would undermine our efforts to live into that 8th Principle commitment.

There is so much that is unknown. There is so much that emerges each day. It can be overwhelming, especially as we are trying to figure out which questions are ours to answer. As we recognize that we are in shock, that there is a traumatic impact for us in this act of violence, we must practice slowing down. We must enlarge our sense of grace towards each other and ourselves. We must practice growing our capacity to tolerate not yet knowing, recognizing that there will come a time when we are not in shock and can begin to make sense, begin to find meaning, begin to right-size the fear or the guilt or the doubt or the confusion or the anger that has suddenly taken up residence within us.

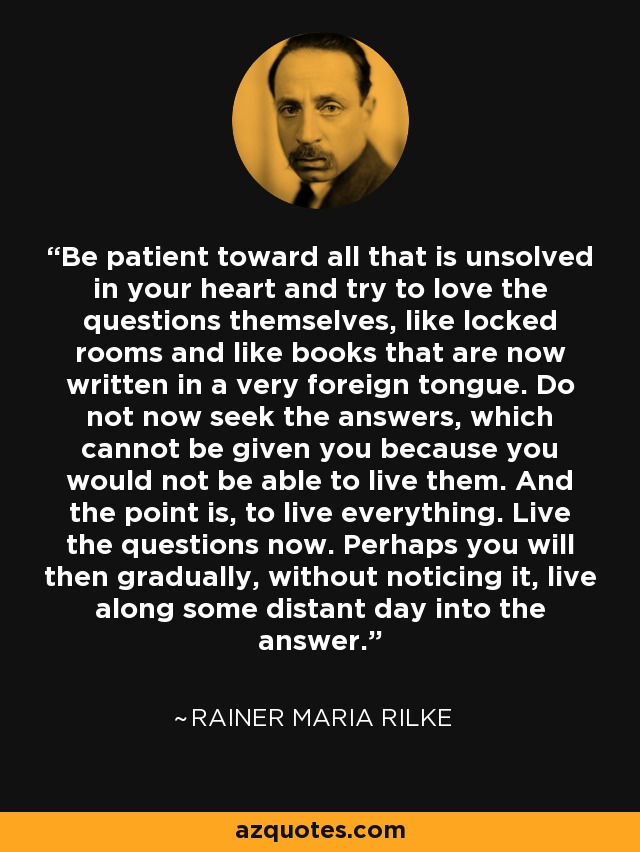

With that in mind, I want to end this part of my message with these words from the late 19th century German poet, Rainer Maria Rilke. You might be familiar with them.

We move out of shock into the next phases by gathering together, by making sense of this senseless act together; by making meaning together and strengthening our connection to each other in community, as well as to our own moral conscience and our collective moral compass.

Part II

As ever, we look to our Principles and Values to help guide us in easy times and in hard. Friends, this is, indeed, a hard time. One that will not go away with the next news cycle. For now, and for some time to come, this is ours to reckon with.

When that gun was fired, we became bound to those three young men whose bodies were forever changed by this violent and hateful act. We are now bound to Tahseen Ali Ahmad. We are now bound to Hisham Awartani. We are now bound to Kinnan Abdalhamid.

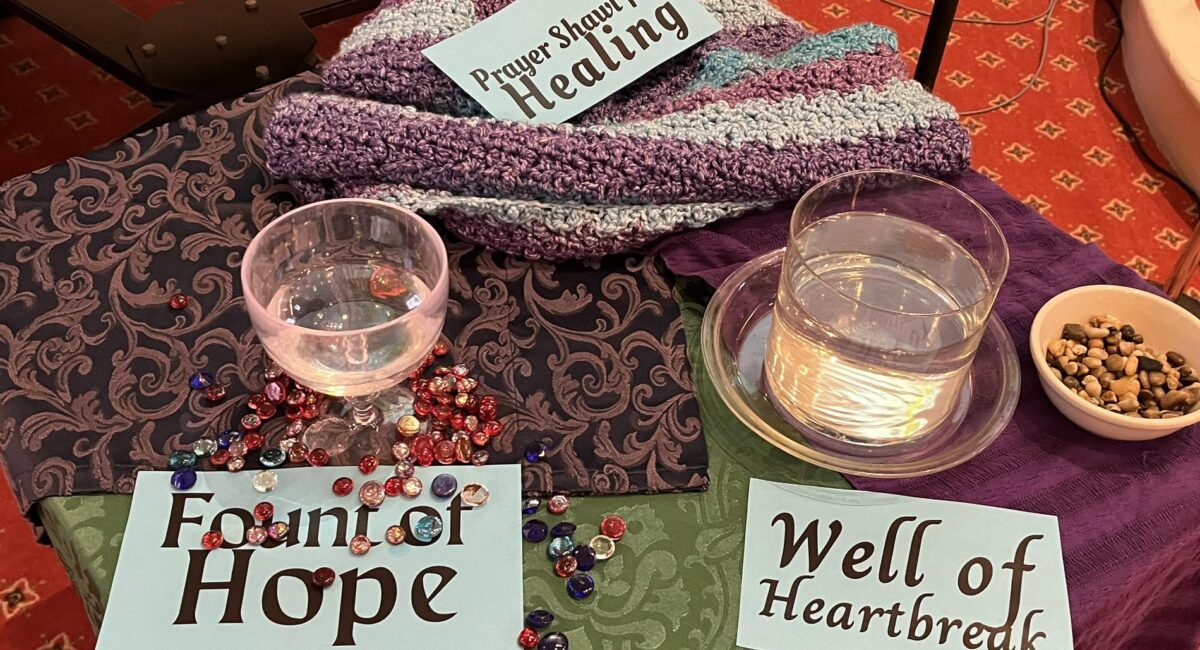

This past Wednesday, our congregation hosted a community vigil ~ an interfaith vigil ~ on Wednesday evening. We sang and we lit candles. 120 people. 150? I don’t know. Behind the scenes, the clergy created space safe enough so that it might be interfaith – which has not been easy to do, given the divisions around Israel/Palestine. This meant it was a no-poster space, even if those posters said “love” or “peace.”

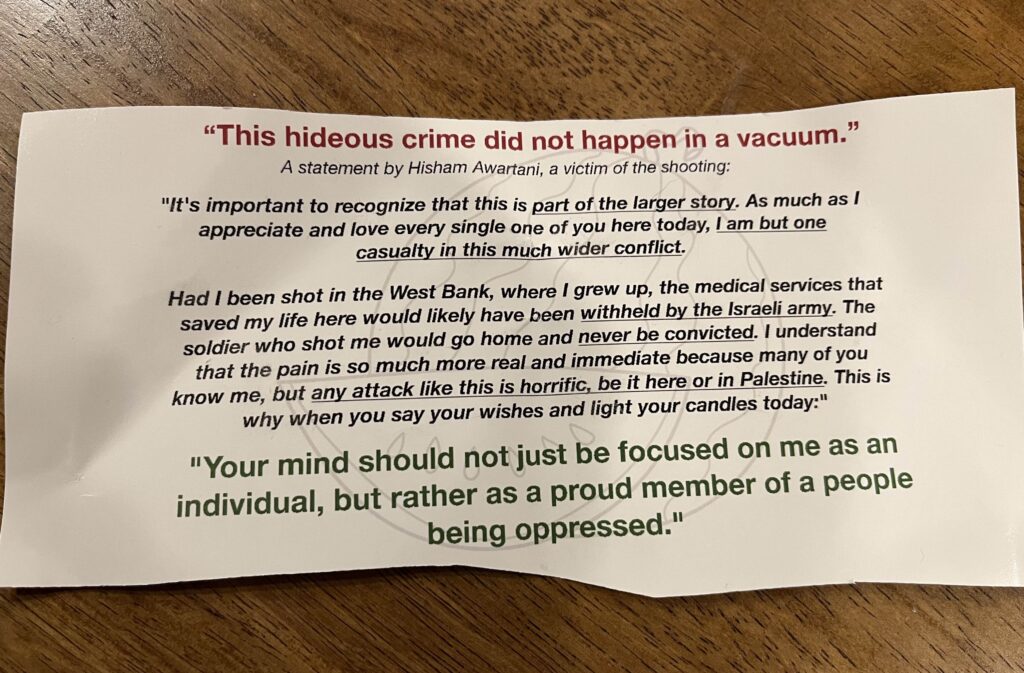

As is common these days when organizing a public event of this nature, we had “boundary keepers” to help keep the peace. So, when someone approached the vigil, wanting to hand out a printed statement, there was an intervention. Our boundary keepers respectfully negotiated a compromise: hand out the slips of paper after the vigil was done. I found out about this after the fact since I was busy with James up front. Those boundary keepers did the right thing, but it turned out to be complicated.

But here’s the complicating, confounding, poignant thing: the statement written on the slips of paper ~ THIS slip of paper ~ is from one of the victims of the shooting. From Hisham Awartani. He wrote it specifically for vigils being held in his name, knowing there were many happening, knowing he could not be at them, knowing that people were gathering in his name.

We are bound to Tahseen.

We are bound to Kinnan.

We are bound to Hisham.

The fates have flung us together. Because it happened in Burlington. Because the likely shooter identifies as Unitarian Universalist. Because he attended this congregation for (yes) less than half a year and stopped (only) a month or two ago.

We are bound to Tahseen.

We are bound to Kinnan.

We are bound to Hisham.

And so, I think it is important that in this space that is our space, which is not an interfaith space like our community vigil was, but is home to a diversity of theologies, a diversity of cultural and religious identities, and a diversity of political opinions on Israel/Palestine, that we read aloud the statement. It may not reflect your views or mine, but that is irrelevant. This bond that we now have requires that we give voice to this statement.

The fates have flung us together. It’s something we must take seriously.

Is it an invitation?

Is it a demand? I’m not sure.

Can we ignore it?

Is it real only if we agree to it? I don’t think so.

Does it exist only if they acknowledge it? I wonder, but I’m not sure.

I think we are now bound together in ways that are inexplicable and will reveal themselves, sometimes only if we are willing to look and at other times, by hitting us on the head.

We are bound together in ways that we do not yet know and in ways that do not yet exist, that might exist, depending on the meanings we create and choices we make. Choices like dedicating this morning’s Share the Plate recipient as the fund that benefits them in the aftermath of the shooting and in the wake of their injuries and recovery needs.

Perhaps the prayer shawls will be another of the ways in which we are connected. Though we will need to approach this with exquisite sensitivity, being guided not by our loving intentions, but by the impact on what it means to the family to receive such shawls from us. There is time to figure that out. We need not figure it out right away.

It makes sense that in the face of senseless violence, we will be longing for safety and wanting concrete information about how we protect ourselves. It makes sense that we are longing to come up with ways in which we can guarantee the safety of our children, of our loved ones, of ourselves. It is understandable that some of us are worried about the risk of gathering, so much so that we are wondering whether it is worth it to gather.

We are not the first, nor are we the last, to ask these questions in the wake of senseless violence, the wake of hate-motivated violence. The most poignant thing I have heard from both the mother and uncle of one of the victims was the reflection that those young men were supposed to be safer here in the United States than in the West Bank.

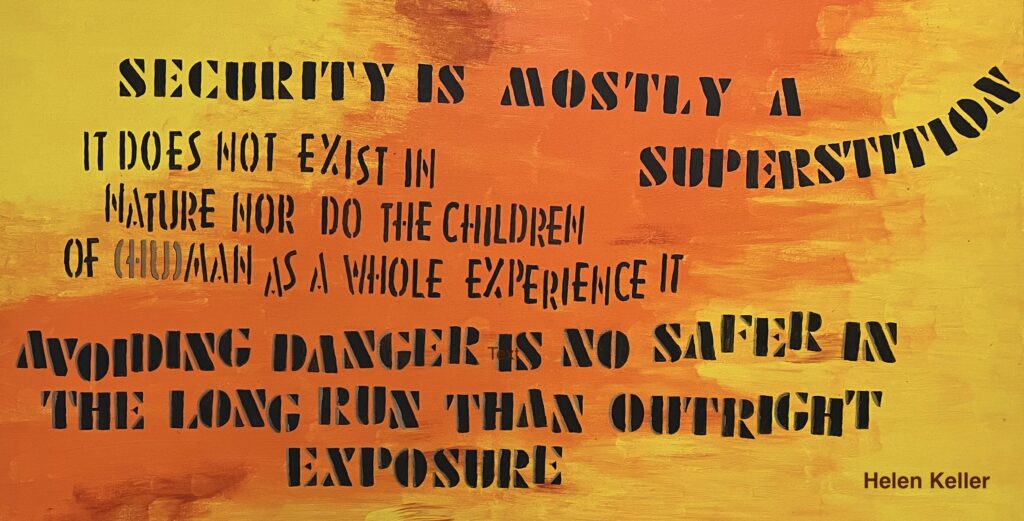

When I notice within me that longing for safety that the world cannot grant, my mind turns to this quote from Helen Keller, which is actually on a large canvas in my garage:

I do not want to downplay the fear that is at the heart of these questions. Neither do I want to give over to that fear. Neither do I want that fear to become the only voice you or I listen to when we make decisions about our communal life and who we are called to be in the world. I am committed to recognizing the rise of fear within me, and not letting it reside there and not letting it guide me.

I want to ask the same of you.

And I am asking that of us as a community, and as a community partner in our local community, and as a religious institution. While we can let fear inform us, we cannot and must not let fear lead us. We must reckon with what it is to live in a world where there is always risk.

Our Unitarian Universalist Principles and Values are better guides than fear.

When we experience tragedy or loss, personal confusion or societal chaos, we come together to make meaning and to experience comfort. It is what we are doing right now. And since we are a people in covenant with each other, we do this meaning making while paying attention to how we treat each other; to how we honor each other’s inherent worth and dignity; to how we lovingly hold each other accountable; to how we are willing to listen to understand even if we do not agree; to how we want to be our best selves, living into our Principles and Values.

Friends, we have been propelled into a territory of trauma and meaning-making. This territory can provoke all sorts of unpleasant behavior – short tempers, crying jags, feelings of overwhelm, aggressive language, blame and resentment, conflict, and more. In the next weeks and months, let’s commit to granting ourselves abundant grace. We’re going to need it.

Yet here’s the unbidden gift: depending on how we engage this territory of trauma and meaning-making, growth ~ and perhaps even transformation ~ can happen. This is where deepening happens. This is when the sh*t gets real. When we face the pain. When we do not seek or accept simple answers. Transformation is only possible, not promised. But it is possible to those who are willing to risk.

In addition to asking us not to let fear guide us, I want to ask us, while we are in the territory of trauma and meaning-making, to stay connected. To keep coming back. Even when we think it’s not worth it. Even when we are exhausted. Especially when we hear that inner voice saying: I’ll go next week.

We close with this poem, written ages ago by your minister.