First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

November 12, 2023

“Tengo miedo.”

I was just about to go on the down escalator when I heard those words.

“Tengo miedo.”

This is a true story. I was at Chicago O’Hare. I was heading to baggage and I heard these Spanish words. I looked and saw a woman at the top of an escalator, frozen, not moving her foot onto the moving staircase.

“Tengo miedo.” I am afraid.

I did what you might have done. I stopped. I offered for us to go onto the escalator “juntos” (together). I offered my hand. She consented. She gripped my hand like it was her only lifeline. It was intimate. It was thrilling. And then, so quickly, we were on solid, stationary ground.

There is more to the story, but that will be for a different time. Not to diminish the reality of her very fear, but: o, that banishing all fear from our lives were as easy as this! May we all have the chance to be companioned in this way when fear gets the better of us. May we all be alert to the chance to be that companion to someone else, especially a stranger.

~~~

The author, Nikki Giovanni, wrote about fear and how it is sometimes a good thing:

Fear tells you not to lend your cousin money; don’t go down that dark street, girl; take yourself home from this party now. Fear is a warning signal. Healthy. Good idea. That fish smells funny. My dog does not like this man. The planet is getting hotter. Fear is a good thing.

And she also wrote:

…it’s not fear itself that causes problems, it’s when hatred is combined with it. Hatred is a bad idea. Which is why it’s cheap and available anywhere you look.

I will say, it’s not just when fear is combined with hatred that it’s a bad idea. It’s also when it’s combined with some paralyzing agent or with the delusion of exceptionalism, or the myth that we are separate from each other. That, too, is a bad idea. That, too, causes problems.

There are so many forms of fear, so many shapes that fear takes. So many fear words:

Dread.

Anxiety.

Worry.

Terror.

Fright.

Afraid.

Scared.

Panic.

Trepidation.

Apprehension.

Existential angst.

Maybe you have other names for fear? Go ahead: say them. Say them loudly so I can hear.

[ ]

I will say that in this past month, my fear about the violence happening in Israel/Palestine, the suffering happening and what it means for the global human community, has been too often embarrassingly crowded out by my fears about the divisions and reactions and traumas and pain around how we try to talk about or engage about or do anything about Israel/Palestine. I know this is messed up, and still this is where I find myself.

I fear the consequences of taking a stance. I fear taking the wrong stance. I fear the consequences of not taking any stance.

I fear touching ancient traumas. I fear doing or saying something that is experienced as diminishing a whole people. I fear that I won’t consider essential historical or political information as I formulate my own understanding of a deeply complex situation in an utterly intractable conflict.

And then, here I am, as your minister, and I fear not having the chops to represent this congregation. Or inadvertently getting us into a hot mess that I did not intend. (Which is different than getting us into a hot mess I did intend.)

Sometimes naming is a form of granting power, an act of empowerment. In this case, when we name the fear we are experiencing, the goal is not to empower the fear but to empower us, to move towards a relationship with that fear that may not banish it, but gives us more agency about how we want to relate to the fear.

Naming fear: the first step to coming into relationship with fear, allowing us to respond rather than compelling us to react. Naming fear silently within ourselves is one thing, and it is a start, but rarely is it enough. In fact, for some of us, it can begin a rumination that makes things worse, not better.

So, naming silently is not enough and neither, typically, is naming out loud, and still on our own, enough. Fear is persuasive and can experience being named in isolation as an invitation to flex its muscles, to see just how much of our emotional landscape it can dominate.

This is a start but naming skillfully requires us to name our fears within a trustworthy container – a circumstance that can hold us, and our fear, without seeding the runaway mind.

A trustworthy container might be another human or set of humans who offer witness to the fear (not necessarily advice, not necessarily counsel, not necessarily problem-solving).

A trustworthy container might be a theological belief about the nature of the universe, for instance, that there is a loving god or that the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice.

A trustworthy container might a spiritual practice, which includes leaning into community, co-creating an embodied reminder that we are never in it alone, even when it feels like it, even when fear is working overtime to convince us as such.

I want us to explore some spiritual practices that help us when we are afraid: Communing with Nature; Singing; and Compassionate Connection. There are, of course, others. Each of these are remedies to fear; each of these available to us as tools to companion our fear.

Communing with Nature. Perhaps you know Wendell Berry’s poem, “The Peace of Wild Things:”

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

In a recent Meet & Greet, though it could have been one of a number of conversations I have had with so many of you, we ended up naming a deep existential angst that seems to be the air we breathe right now. It was the mix of the violence in the Middle East, the growing constriction from the climate crisis, and the serious concerns about the health of democracy in this nation.

This familiar poem suggests one of our strategies for relating to our fear is to find comfort and inspiration in the natural world. The poem is an invitation to remember that there is no separate realm called Nature though our lives often ask us to live in that delusion. That poem is an affirmation that there is an interdependent web of all existence AND we are a part of it AND that it can be a source of solace when despair (another word for fear) overwhelms us, takes up residence in us.

In January, we will be rolling out what I call The Earth Teacher Project. It is an invitation for all of us to intentionally deepen our relationship with the natural world, having each month a different Earth Teacher to act as a source of wisdom and inspiration. Be on the lookout in the eNews, Community Messenger on Realm, and in the internal Facebook page for more details.

Singing. Now, I could preach to you about how singing – the singing of others that we let wash over us, the singing we do in the good company of others, the singing we do just on our own for our own selves. (Or in front of a whole congregation when you don’t have the most musical of voices.) All these can be remedy for fear.

I could preach about these. But, instead, let’s listen to the choir not preach, but embody this for us. In fact, it’s not just the singing they bring us, but the message of the song, Psalm 23, that affirms the trustworthy container that some of us lean on as well: a comforting Sacred Source, a loving god.

Part II

Compassionate Connection. In Buddhism, compassion is one of the Four Great Virtues. Each of the Four Great Virtues has a far enemy, which is basically its opposite. In compassion’s case, it’s hostility (or hatred).

Then there is also a near enemy. This is trickier than a far enemy, because near enemies disguise themselves as if they are the Great Virtue itself. We humans are easily confused by them. Typically, the near enemy of compassion is considered pity which contains veiled condescension, can involve victim-blaming, and falls into the delusion that we are separate from each other. Recently, one of my Buddhist teachers (Upayadhi) offered a different name for the near enemy of compassion. It was “horrified anxiety.”

Horrified anxiety buys into the distance and separation thing – horrified for them, rather than horrified for us. It’s also got a semi-competitive quality to it, a way to indicate to others our level of both compassion and compassion fatigue in the world. It’s also has this strange double quality of letting us off the hook while also paralyzing us. It can take the form of a ruminating anxiety, or an anxiety that convinces that our only option is to opt out, to numb out, to leave it to others, because it’s so overwhelming, it’s so too-much.

Anybody here know this form of fear? In others around you? In yourself? I recognize versions of it in me. For sure. And I think I’ve seen it floating around here as well.

Rabbi Irwin Keller, of Congregation Ner Shalom in Sonoma County, California, preached just yesterday about a version of this. Listen to his description:

In the mad scurry of people staking out their positions and signalling to their allies, I’ve found myself frustrated, upset with the policy positions and slogans of people with whom I mostly agree. Feeling like they are using words that will divide us more than they unite us. And then all the moreso people whose positions and slogans horrify me. And I see us, all of us, trying to latch onto one of those positions or one of those slogans, maybe just to have something to hold onto. It all gets me going; I feel my nerves fraying in real time.

“Rely on Compassion” by Rabbi Irwin Keller

In Buddhism, the remedy to both fear and this near enemy of compassion, whether it’s pity or horrified anxiety, is acts of compassion.

Key is the whole phrase: acts of compassion. Not just compassion, but actions that are generated by the suffering-with that is compassion. By this, I mean acts that do not solve all the problems or save the whole world or permanently and perfectly fix even our small corner of it. When the scale is as absolute as that, it is too easy to fall into that horrified anxiety, to find ourselves daunted because we have created an impossible standard that paralyzes us in fear, rather than prompts us into generative acts of sustainable love.

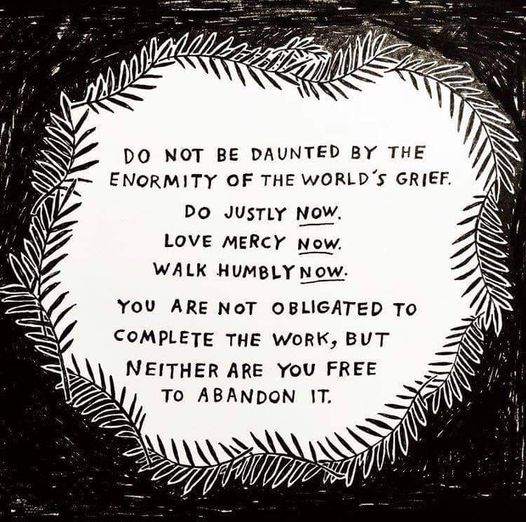

It is in moments like that, when I am stymied, paralyzed, when fear takes on the name of “being daunted,” that I remember the following wisdom from the Talmud, articulated in this particular way by Rabbi Rami Shapiro:

In the face of my own being daunted by how to respond faithfully in the face of what is happening in Israel/Palestine, I have – so far – found small acts of compassion that I hope are leading me to clearer, bigger acts of faithful clarity. And as Rabbi Keller, whom I quoted earlier said in his commentary this week, “I would rather make decisions based on compassion that don’t go so well than make decisions based on fear that end up fueling more fear.”

I’m going to share a bit more of Rabbi Keller’s sermon from yesterday, in hopes it might offer you the same glimmer of hope, so rare these days, that I experienced in reading it:

I said that the Torah portion begins with a death and ends with one. It ends with the death of Abraham. He has remarried, he has had more children, and now he breathes his last at the ripe old age of 175. And then something remarkable happens that Torah seems to find utterly unremarkable. His sons Ishmael and Isaac come together to bury him. The story of those brothers is a setup for us to imagine them locked in a lifelong enmity. But Torah gives no evidence of that. In fact, for Ishmael to have arrived in time for burial he would have had to be there already. Isaac and Ishmael, together not only in burying their father, but in caring for him together in his final days.

As the sun sets on this Torah portion, there they are, these two brothers, the mythical forebears of the Jews and the Arabs, old men already in their own right: Ishmael 83 and Isaac 75, the age that the State of Israel is now. Together they grieve. They grieve their father. They grieve the lost opportunities to heal their family. It is a terse moment in Torah, but it smacks of compassion; it smacks of love.

This is the lesson that Torah is whispering to me this week: at the end of the day, at the end of the story, love. Love. Love that is formed by shared experience and by destiny. Love that is intertwined with grief. Love that does not need everything to be fixed. Love that does not require just the right words. But Isaac and Ishmael, shoulder to shoulder at the grave, honoring the past and burying it, for both their sakes.

“Rely on Compassion” by Rabbi Irwin Keller

It is in small acts of connection and true acts of compassion, trusting that in the many overlapping circles of community, there will be enough (there must be enough), building on one another, that we will find our way, not right away, but eventually, especially when we remember that it is not ours to complete, but neither is it ours to give up.

We never know whether it will be us at the top of an escalator, speaking our fear to the universe or whether it will be us who hears that tiny fearful call for help… and decides to listen and act.