Originally titled, TBD – to be determined – this wasn’t exactly false – it did get determined before the title was formally announced in the monthly news. In the writing of last week’s sermon, which was ending up clocking in at close to a half hour, it became clear that this morning’s sermon would need to be Part III of last week’s Parts I and II. So, you can think of today’s Sunday service being either To Be Determined; or Teaching Goodbye, Part III; or what I have come to call it: Four Phrases of Goodbye.

This goodbye we are embodying is not the Big Goodbye – the kind we say when a life is ending. And yet, it is a significant goodbye as it may well be the last time we, who came to love each other, see each other or communicate with each other. Let’s call it a “medium-sized” goodbye.

As such, there is wisdom to be gained from Dr. Ira Byock’s book, The Four Things that Matter: A Book for the Living. In it, he identifies four phrases to say or follow as someone is dying. I preached on them in October, but I don’t expect you to remember:

I have been thinking about this guidance as it relates to my conversations with you – you collectively, you individually. I have been wondering what I need to say to seek forgiveness, what I need to say to express forgiveness, what I need to say in terms of gratitude, what I need to say to reiterate my love for you and our time together.

In seeking your forgiveness, I think of our offertory from Hamilton the Musical. Titled “One Last Time” it is about George Washington’s decision to step down as president. In it, the character returns again and again to the phrase about teaching them (in this case, the nation) how to say good-bye.

The song includes actual lines from the farewell address of the first president of this country. The lines cited are condensed from the actual farewell address which was 32 pages long (it was published, not delivered as oratory). Here are the concluding paragraphs, in that condensed form as delivered in the Musical (but pretty darn faithful to Washington’s actual words):

Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. I shall also carry with me the hope that my country will view them with indulgence; and that after forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as I myself must soon be, to the mansions of rest. I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I promise myself to realize the sweet enjoyment of partaking, in the midst of my fellow-citizens, the benign influence of good laws under a free government, the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust of our mutual cares, labors, and danger.

“One Last Time” from Hamilton the Musical

So yes, please forgive me my errors. My aim will always be to maximize the chances for future healthy ministries. This has been true not just in this transition, but throughout the whole of our seven years together in shared ministry. Please view my errors with generosity of spirit, or with “indulgence” the language used in the farewell address. One way of asking, “Please forgive me.”

On November 6, 2016, the Sunday before a rather infamous election, just three months into our shared ministry, I preached about an early interaction I had with one of our kiddos during a Time For All Ages. I asked a question and one kid raised his hand at lightning speed. When I encouraged him to share, he hemmed and hawed, then acknowledged that he was too nervous to speak because he might get the answer wrong. Not wanting him to be alone in that vulnerable space, I joined him, sharing that I, too, was afraid of getting things wrong. In the November sermon, I preached these words:

The only saving grace I have found about that heavy weight of fear of doing something wrong, of not having the right answer or even worse, having the exact wrong answer, is the strange paradoxical true truth that I will get it – will get some thing… some things [plural] — wrong. It is inevitable.

I will get something wrong far more often than I want to. And more often than you will want me to. It’s what ministers do. It’s what humans do. We’re weird that way.

“B-R-A-V-I-N-G,” November 6, 2016, Karen G. Johnston

So in the midst of getting something wrong, in the midst of unintentional errors, I beg not only your indulgence, but also your forgiveness.

~~~

In the spirit of mutuality, because we ~ not just ministers ~ are weird that way, I offer you my forgiveness, aiming to do so with indulgence, with generosity, with abundance. Aiming to do so lavishly, not because there is so much to forgive, but because I wish to grow this capacity in me, as a form of spiritual practice, of wanting to generate less regret or resentment and more gladness in myself and in the world.

And I’m not even sure forgiveness is the right word, the right concept. Instead, I want to lean more towards the concept I hear more often in Buddhism: acceptance. The absence of resistance to the way things are. The capacity to name a quality by observation, not with judgment, like what I aim for when I see patterns in this congregation taking the shape along a continuum of shabby to scrappy, sometimes one, sometimes another.

At the shabby end of the continuum, I must admit that there were times when I experienced disappointment, which given my own temperament and patterns, too often can lead to noticeable judgment. It is here that I cultivate forgiveness. It is here I grow acceptance, for I do not want inevitable disappointment to tarnish our good works together.

And in those scrappy times, there were moments I was filled with admiration for not only your potential, but your actual – like last Sunday’s ordination, like when you raised 40% more money than the goal after the mold fiasco, like how you said yes to being the fiscal agent for a grassroots effort called Lost Souls Public Memorial Project that eventually became its own non-profit. Not too shabby. Not shabby at all.

And gratitude. For so much. This, too, is lavish. Gratitude for calling me to be your minister seven years ago. Gratitude for allowing me into your lives, sometimes intimately, sometimes tenderly. Gratitude for the ways in which I have grown because of our time together. Gratitude for the home Tony and I made at the parsonage (Vera and Riley express their gratitude as well, for they have loved how good that house and yard have been to their dog and cat selves.) Gratitude for my sabbatical in 2021, for your honoring my community-facing ministries of the Lost Souls Public Memorial Project and Date with Death Club. Oh, and not to mention how thankful I feel about how we got through the height of the Covid pandemic together, as intact as we did. That was something!

And lastly, truly, simply: I love you. I knew it when you first called me. I felt it even during rough periods of our shared ministry together when I wasn’t sure that I was cut out for what I was being handed. I felt it and it sustained me in the pandemic (as well as my mini-farm in the Somerset suburbia)!

~~~

Out of my love for you, I have been thinking about this in-between time that has begun for this congregation. In-between Time. Liminal Time. Such a period begins every time a ministerial transition starts. Church consultant Susan Beaumont, in her book, How to Lead When You Don’t Know Where You Are Going: Leading in a Liminal Season, wrote this about the ministerial transition of a pastor retiring, but it fits our circumstance too:

For example, a change occurs on the day a pastor walks out the door and begins her retirement. But the full transition work, the psychological and spiritual work of letting go of that pastor, began well before the retirement date, and extends for a period of years beyond the arrival of the new pastor. The congregation enters a long period of liminality, during which the people learn to let go of identities and behaviors held together by the ex-leader’s presence. A new pastor may arrive, yet the congregation remains in liminal space until the full transition occurs: until collapse of the old identity is allowed. (Beaumont)

At this time, it is not yet known who your next minister will be or when they will begin. There is the search team doing their best, practicing flexibility, learning how to read the lay of the religious landscape, serving the best interest of the congregation, being the first, alongside the Board, to touch the shape of this period of liminality.

For you as a congregation, it is a time of not knowing and learning how to live with that uncertainty, with that ambiguity, how to hold your collective anxiety, while waiting, and trusting, and returning to each other, resting in each others’ presence, and returning, again and again, to your purpose for being, rather than trying to flee the not-knowing and the discomfort that comes with it.

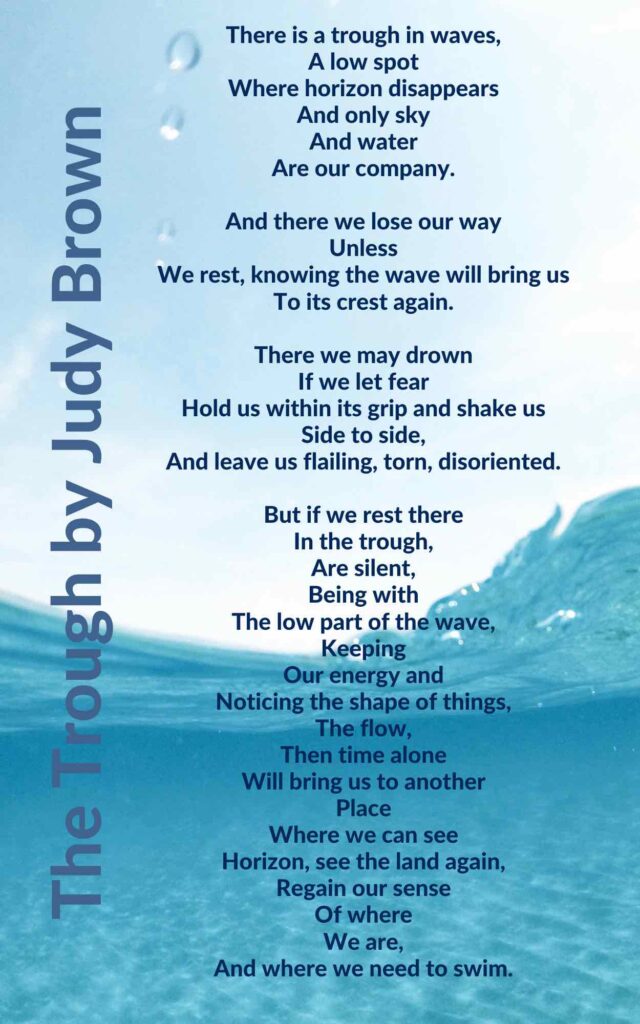

I think it’s like this morning’s reading, the poem, “Trough,” by Judy Brown. I think it’s like finding and then living into, the wisdom described in in that poem:

I wonder if we can find, in whatever troughs we encounter, and particularly those troughs

in the midst of small good-byes, like when we aren’t going to see someone for a long while; or medium-sized good-byes, like the kind we are experiencing with this ministerial transition, with the nature of our relationship changing and our not knowing whether we shall see each other again (despite having an invisible thread that always keeps us connected); or the Big Goodbye that comes when someone is dying; I wonder if we can find in these troughs the courage and strength to “regain our sense of where we are” not just swimming to where we need to swim, but saying what needs to be said:

Forgive me.

I forgive you.

Thank you.

I love you.

So be it. See to it. Amen.