March 12, 2023

The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

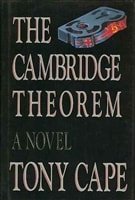

When Tony, my partner, wrote and published his first novel, he fantasized about who would play the lead should it ever become a movie. In his mind, it was the British actor, Clive Owen.

Here is a photo of Clive from that era – 1991 – perfect for the young Derek Smailes. Nothing came of those fantasies. The book remained a book.

Fast forward thirty years later, to now, a time when Tony has turned the novel into a screenplay and is shopping it to producers. This is what Clive Owen looks like now. Derek Smailes’ father, perhaps, but not the detective protagonist.

The processes of mortality have had their wanton way – not just with Clive Owen, but with Tony, with me, with you, with all of us. While Tony’s task is to identify a different actor for his ambitions, all of us – Tony included – have a common task, though it will be unique to each of us: to love what is mortal.

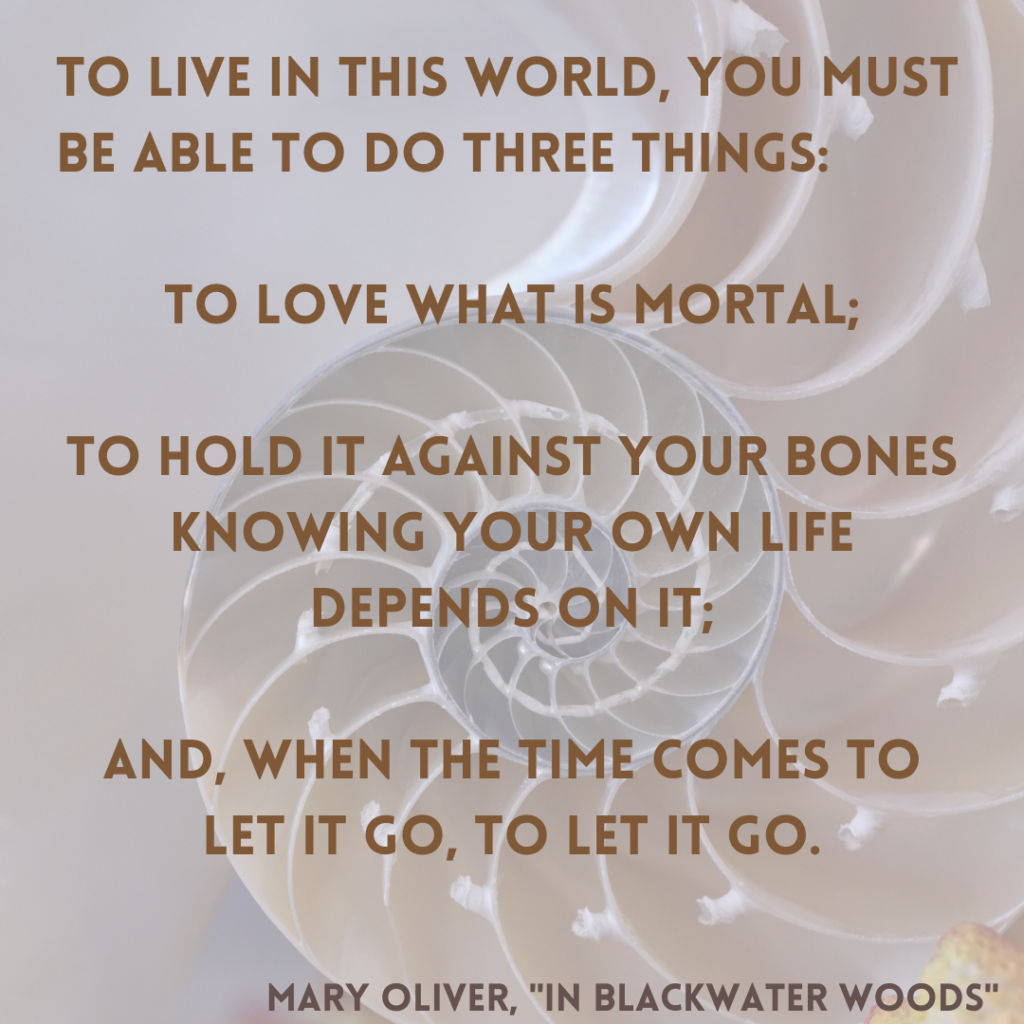

Let me speak those last lines from this morning’s reading, In Blackwater Woods, by Mary Oliver:

To live in this world, you must be able to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it against your bones

knowing your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go, to let it go.

Three such poetic, poignant rules for living, for reckoning with our own mortality and that of all life, of all those we cherish (and despise, and everyone inbetween).

Love what is mortal. Including ourselves, including attempting to love the fact of our mortality, and if not loving it, then coming to peace with it, not acting as if it’s a universal law that applies to everyone else. To conjure some impossible and necessary befriending energy, doing so as antidote, or at least companion, to fear, to resistance, that arises for us from the mere fact that we are human.

Hold it against your bones, knowing your own life depends on it. Bones are so hard, yet the teaching here is not to harden ourselves. In fact, the opposite. So it is here that I want to tell you about octopuses. Octopi.

How this earthling – sea-ling – is the least hard creature we know of, all soft and malleable, except for its beak. It is arguable that the octopus (not the human) is the most evolved species on the planet. In addition to its main brain, it has eight other brains, distributed throughout its body, each of which can make decisions on its own. It has amazing capacities not in spite of its apparent vulnerability, its utter softness, but because of it. It turns out that those species with hard shells – think turtle – are the slowest to evolve, are the most like they were in the beginning of turtle time.

And octopi, because of their soft vulnerability have had to evolve capacities at lightning speed, otherwise they would have gone extinct. Vulnerability as super power. Here is how the performance poet Andrea Gibson describes it:

I learned the octopus has three hearts and nine brains. They can taste with their skin. They can feel light. Though they don’t have ears, they can hear impeccably. They’re also capable of making decisions quicker than any other living being on the planet. And that’s not even to mention their wisdom and emotional depth, which we humans may not yet be evolved enough to comprehend. One could spend a lifetime complimenting the octopus’s history of turning vulnerability into a powerful force for growth.

https://andreagibson.substack.com/p/evolutionary-power-of-vulnerability#details

Knowing our lives depend on it – the dependence and vulnerability of our lives; our society’s rampant and ruptured individualism that actively obscures and systematically denies the truth of our interdependence (yes, our DEpendence overlapping with our INDEpendence morphing into INTERdependence). Yet we have this so-called vulnerability of needing others, of needing each other. Portrayed as weakness, it is our strength (if we do not resist it, but surrender to it). Don’t let anyone tell you different. Don’t let some internal voice persuade you otherwise. Heed the wisdom of the octopus.

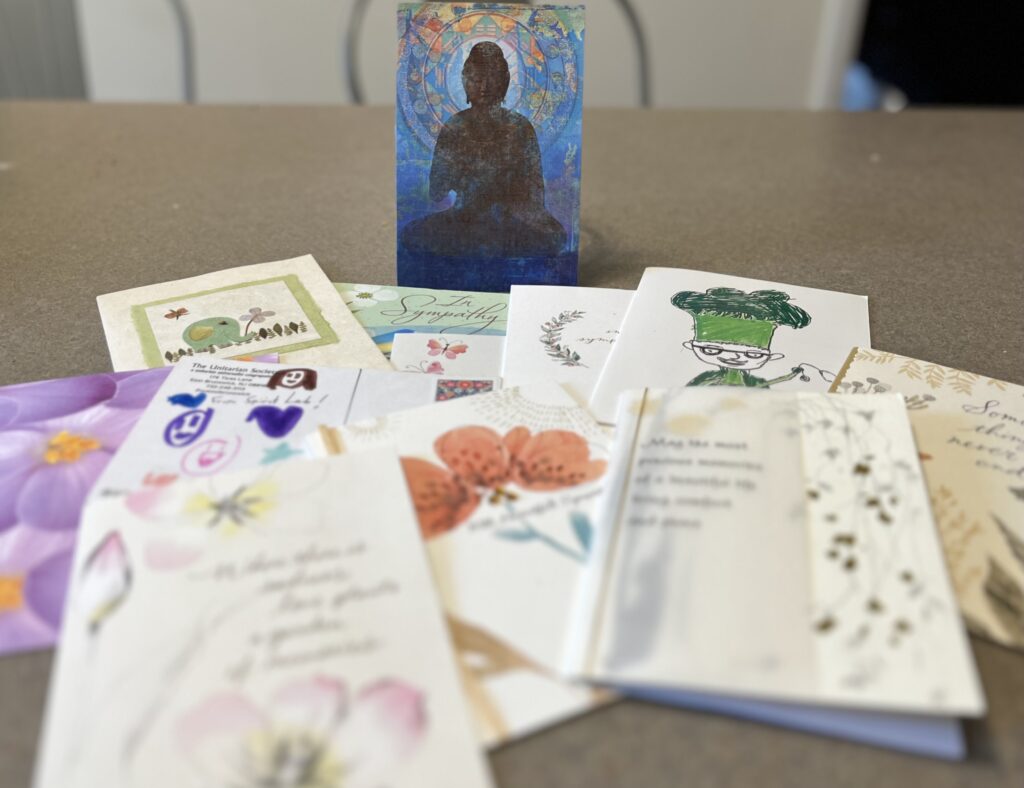

It is here I want to thank you for the plethora and abundance and surfeit and glut and superfluity (l leaned hard into the thesaurus for this sentence) of support you have given me. Messages to go slow. Cards that have flooded my mailbox since new of my mother’s death. At least one email recognizing how nuanced it is for a minister to accept help from the congregation at time like this. Chocolate (no need for more, thank you though). Offers of coffee. Gentle questions about whether I should be working and attempts to make sure I know that I can take time off.

The book at the heart of our Time For All Ages story – The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Macksey – includes a preface that encourages the reader to go through the book however one wants – start to finish or open to a random page. The book is a sort of compilation of meditations on life and so each page or set of pages offers its own commentary.

So many of the truisms speak to me. Especially this one:

“What is the bravest thing you’ve ever said?” asked the boy.

“Help” said the horse

Please know that I have asked for help in bold and frightening ways since I learned my mother was dying. It hasn’t necessarily been from you, but I have been trying to practice what I preach. That said, if you are still looking for ways to help me, you can talk to Doug Liebau about an offer of help he has made that I have humbly accepted.

Three: And when the time comes to let it go, let it go. Oh my. We all get to practice this. In small ways. In large ways. In personal ways. In community ways. The pandemic gave us all lots of practice, whether a loved one died or not. We had to let go of many things. Such is the nature of life, to have to let go, yet some of us struggle with this more than others; all of us struggle with some lettings go harder than with other lettings go. I think here to the page in the book from our Time For All Ages:

“When our hearts hurt?” asked the Boy.

[To which the Horse responds]

“We wrap them with friendship, shared tears, and time,

till they wake, hopeful, and happy again.”

Next week, I was already planning on going on study leave. And I will be away from TUS. But instead, I will spend some of that time sitting shiva in Chicago with my brother and his family. In the way of interfaith families, my mother was not Jewish (and my own Jewish pedigree is complicated and more “ish” than Jew). Yet my brother and his family are Jewish, so they will follow this communal religious custom and I have been invited in. Such a poignant embodiment of the letting go necessary, yet doing so while one is being held. A compelling container to let grief have its expression and its witness, not in isolation, not in distraction, but among people enacting an ancient tradition. Well, not octopus ancient, but human ancient.

These three instructions – pieces of advice – rules for living, whatever you want to call them: they are distinct, but they do not exist apart of each other. They merge and mingle, they become confused, one for the other. The practice of one leads us up against the next or the prior. They might co-exist in a circular relationship, but my hope is that it is more like a spiral. Perhaps leaving us more emotionally vulnerable than feels comfortable, but perhaps also helping us to be more existentially resilient, more spiritually skillful?

That is my take on them. That is my hope for us.

So be it. See to it. Amen.