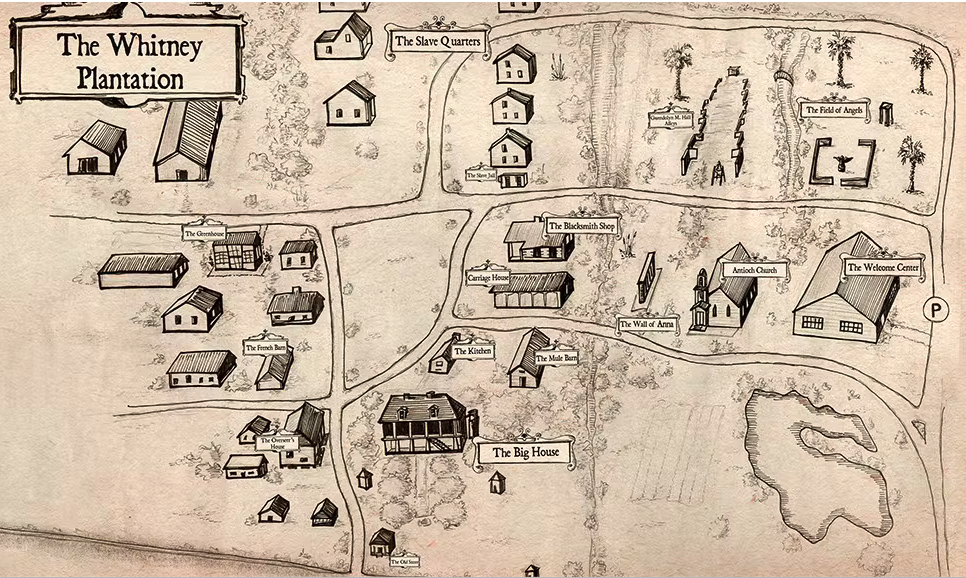

Leaving New Orleans this morning, I spent several hours today at the Whitney Plantation, on my way to Baton Rouge. The Whitney Plantation is the first former-plantation that has been turned in a museum that focuses solely on the experience of the enslaved. Founded in 2014 as a museum, it was only in the past few years (2019) that the founder the museum, a white lawyer from John Cummings, turned over the leadership of it to a board of trustees. It now operates as a non-profit organization with an educational mission.

While there is some criticism to level at the Whitney, most of what I have been able to find speaks affirmatively to the efforts to center the experience of the enslaved. This is particularly true, given how most other plantation museums fail spectacularly in this regard. I particularly appreciated the strong focus on resistance among the enslaved, including a powerful and reverent installation marking the 1811 slave rebellion on the German Coast and the resilience of enslaved mothers in the face of high mortality rates of their children.

I chose to spend my limited time with a visit to the place because of its commitment to center the experience of the enslaved. And I went because the Whitney has what they call the Louisiana Slave Memorial or the Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, which contains 107,000 names of enslaved persons in Louisiana from 1719 to 1820.

Up to 1820. That caught my attention! The Lost Souls were brought to New Orleans in 1818, some of whom were likely headed for the plantation owned by one of the slave ring leaders, Charles Morgan. We don’t know what happened to the Lost Souls once they got to New Orleans, but there are reasons to believe that some ended up in Louisiana. In two places in particular that I will be visiting in the coming days!

Not knowing what the memorial was like, or actually understanding how vast the number of names it included, I wondered if I might be able to find some of the Lost Souls. Maybe it would be organized in such a way that would help make a connection? It was a stretch, but worth checking out.

As it turned out, it was a stretch too far.

The tour is self-guided, with an official recorded narration that you listen to with a headset. When you get to the Louisiana Slave Memorial, you learn that the data base created by Dr. Gwendolyn Midlo Hall was extensive. It included not only names and ages, but also information such as birthplace, languages spoken, and trades skills. The memorial is mostly first names – the rest of the details from the database remain in the database. It could be that the database itself might be organized by year; the memorial is, most certainly, not.

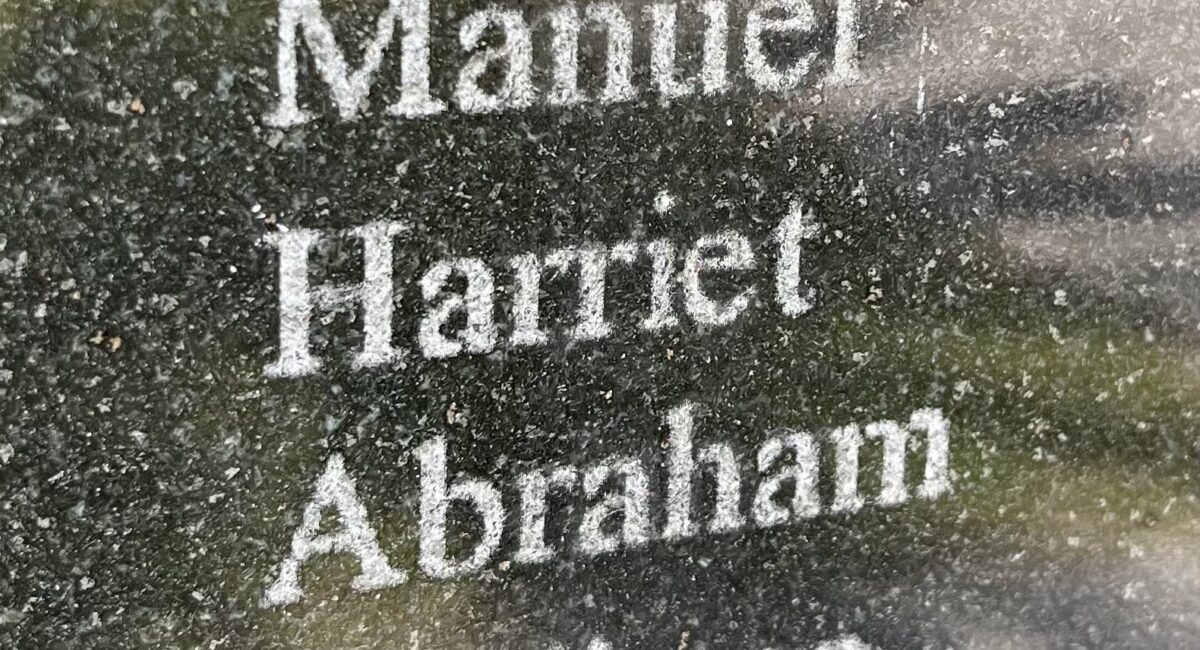

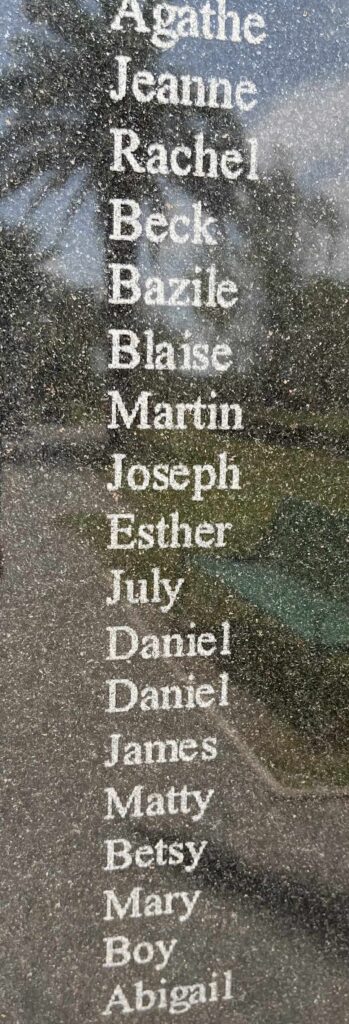

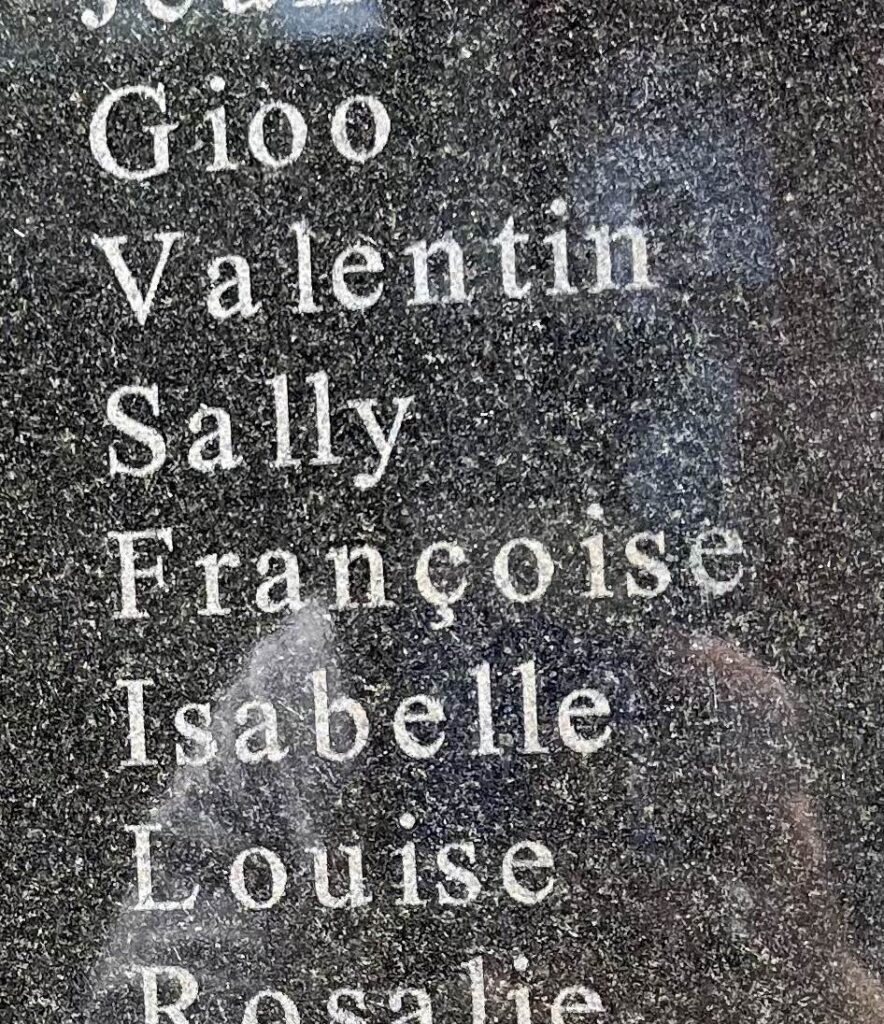

So, while there are names on the walls that are the same names as the Lost Souls, there is no way to know whether the Harriet inscribed on a wall is, or is not, the Harriet from our list. Or the Charles. Or Nancy. Or Sam. Or Sally. Or Betsy. Or Rachel. Or…

And there are 216 granite slabs which are mounted on 18 walls! It’s a huge number of names. There were a mind-blowing number of enslaved persons in Louisiana in that hundred-year period alone. According to the museum narration, the database is not definitive – it most likely does not include all who were enslaved in Louisiana in that time period.

There are other reasons I am glad that I made this stop on this pilgrimage. I was able to offer the doubly blessed homegrown holy water at two spots on the grounds of the museum that have become shrines. I’ll write more about that at another time.