(this post is the second of a two-part report on my visit to Morganza; the first part can be read here)

On Sunday, April 3. The sun was shining. I was driving an hour away from Baton Rouge, heading to the tiny town of Morganza, the site that first came into my imagination when I began considering this pilgrimage. Why Morganza?

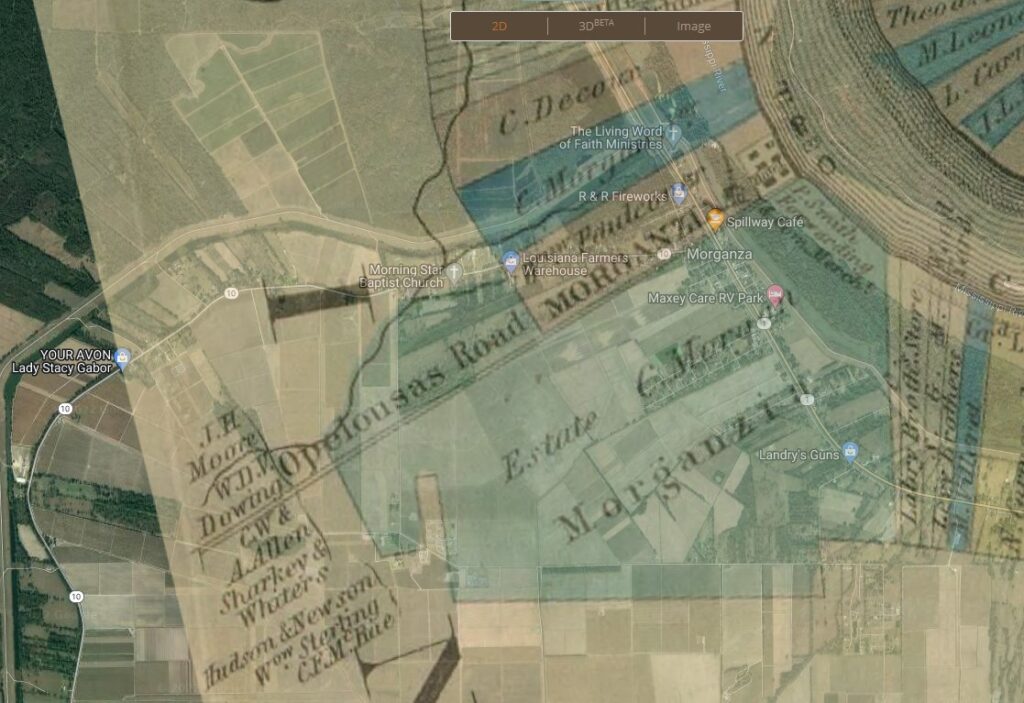

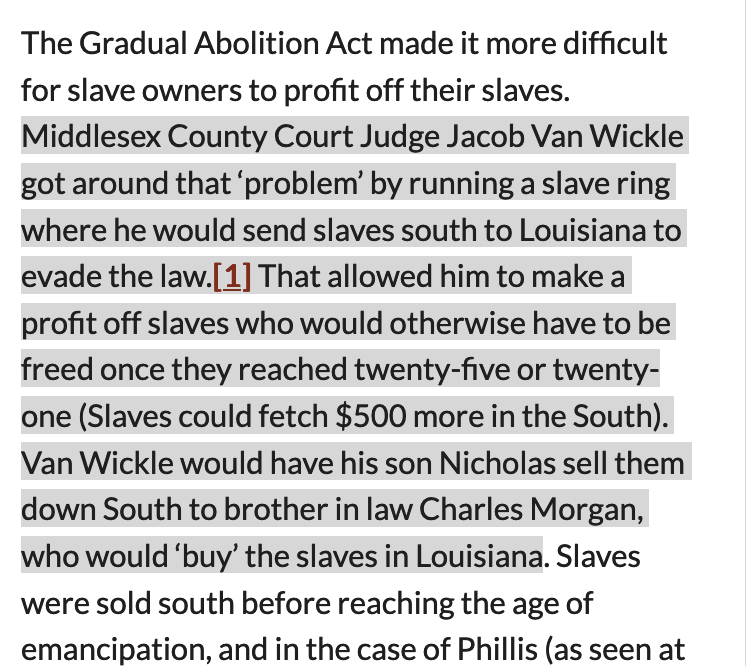

The slave ring that stole the at least 137 African American women, children, and men from New Jersey and sent them into the Deep South was actually a statewide network of white supremacy abusing legal and judicial power. While Judge Jacob Van Wickle is understood to be the head of this slave ring, there were dozens who were actively involved and this included Van Wickle’s brother-in-law, Charles Morgan. From a prominent New Jersey family, in 1818 Charles Morgan was a state senator and owned land in Louisiana along the Mississippi ~ a plantation he called Morganza (or Morganzia, as the 1858 map calls the property).

I’ve also learned about Morganza from one of Charles Morgan’s descendants, Dr. Allison Bailey, who has done extensive family genealogical research in order to uncover and cultivate accountability for her family’s enslaving actions. She has written about this, including a chapter in her book, The Weight of Whiteness: A Feminist Engagement with Privilege, Race, and Ignorance.

While it is not known with certainty where the Lost Souls ended up (there are indications that they ended up in multiples locations in multiple states), it is reasonable to suspect that some were intended for Charles Morgan’s plantation and may well have ended up there. There are many tragic, unjust aspects to the story of the Lost Souls. One of them is that some of the Lost Souls were already free before they were either deceived or kidnapped down South. Some, and likely most, would have experienced emancipation at the ages of 21 (for women) and 25 (for men) in New Jersey. Yet in Louisiana, liberty was not their destiny; instead, slavery for themselves and for some part of their children’s and grandchildren’s lives, was their likely fate.

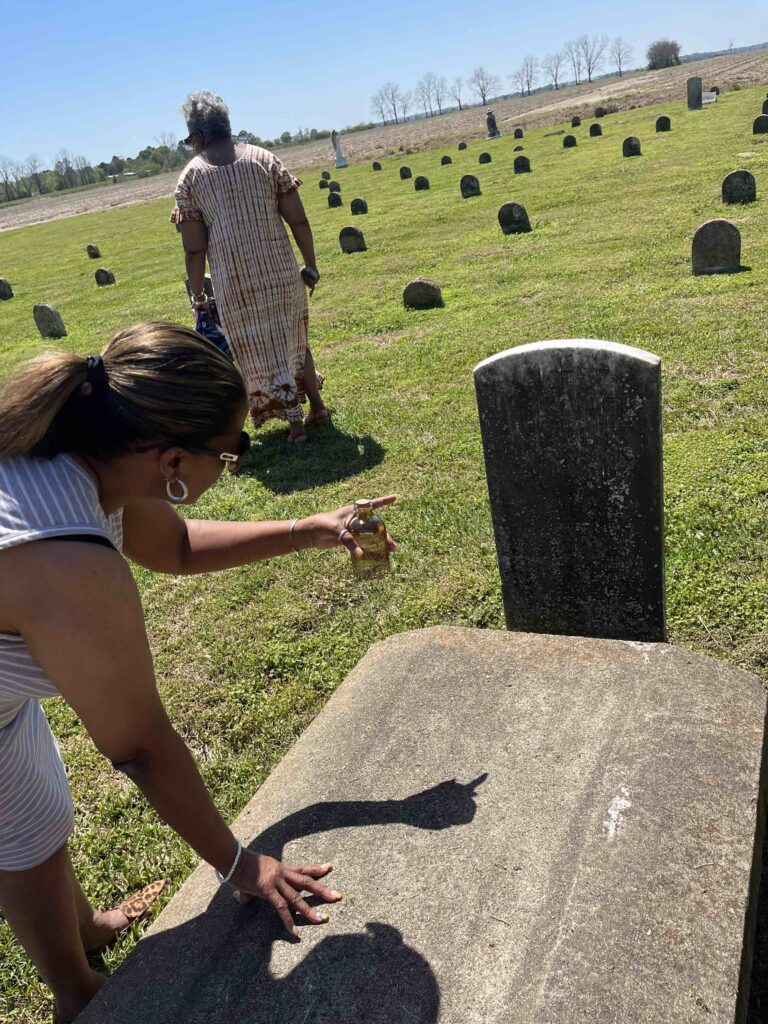

As part of this pilgrimage of visiting locations related to the Lost Souls story, Morganza struck me as essential. It made sense, in making preparations to visit Morganza, to connect with individuals familiar with the area. I reached out to Ms. Kathe Hambrick, public historian and founder of the River Road African American Museum. It turned out that Ms. Hambrick was personally familiar with the area. You can read more about her in an earlier post. Given how knowledgeable she is and how dedicated to rural Black communities along the Mississippi she is, I was thrilled that Ms. Hambrick had found time to visit Morganza with me. Little did I know that she had even more in store.

When I met with her in the town of New Roads, she informed me that she had found someone who grew up in Morganza who was available to take us on a tour of the little town. So, Ms. Hambrick got in my rental car and we drove the twelve minutes over to Morganza to meet up with Ms. Faye Oliver.

What a gift Ms. Oliver turned out to be !

I shared about the history of the Lost Souls of 1818, their possible connection to Morganza, and about the Lost Souls Public Memorial Project, with its intention to uncover the history, educate the community, and build a memorial centering the experience of the Lost Souls. This had been new information to Ms. Hambrick when I told her about it over the phone. It was new information to Ms. Oliver.

Together, we sparked about possible connections, ideas, and next steps. That was one of my hopes for this pilgrimage: to make connections that might be of benefit to a Greater Good.

Yes, to be of benefit not to the Lost Souls Project, of which I have been a part for its four-and-a-half year existence. But also to be of benefit to in unexpected, unforeseen ways.

To be of benefit to friends, new and those I have not yet met, if this connection with Morganza turns out to be true.

To be a part of those generations that have come before, and will surely continue, generations led by the courageous efforts of uncountable African American people, a collection of individuals, organizations, and communities which refuse to accept whitewashed history.

To be a part of the process of liberatory memory – using our collective remembering and our moral imagination to center those who have been harmed as one of the ways we reduce future trauma and harm.

To be a part of the collective communities and individuals who prioritize truth-telling, seeking it to benefit a communal healing and a greater (to use Ms. Hambrick’s words) “reconciliation.”

May these efforts honor those from whom freedom was taken away. May these efforts honor those who daily survival was a form of resistance. May these efforts, in whatever ways are available, cultivate possibilities of healing through justice, of accountability through reparations, of Beloved Community through truth-telling and integrity.

The video had me in tears!