Better poets and theologians have made their offerings. Who am I to attempt to join them? Yet, because Universalism tells us we are all loved and since Universalism tells us we all have a role in collective liberation: who am I not to? So, I humbly offer this hoping it yet is enough.

Near the end of the journey one makes through the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, there is a poem. Inscribed in marble, it is “Invocation” from Elizabeth Alexander, which Theodore Wheeler rightly describes as “emotional coda for the experience.” You can read the whole text of the poem here. For the purposes of this post, I am pulling out two sections, one section of two lines and another section, with the four final lines of the poem.

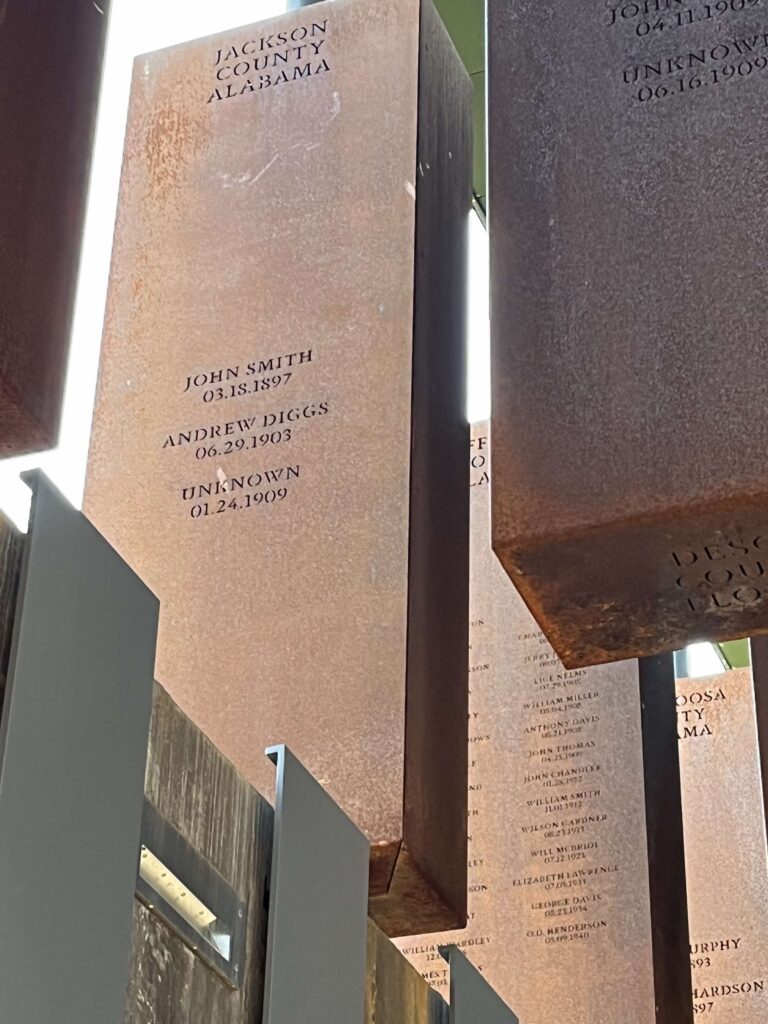

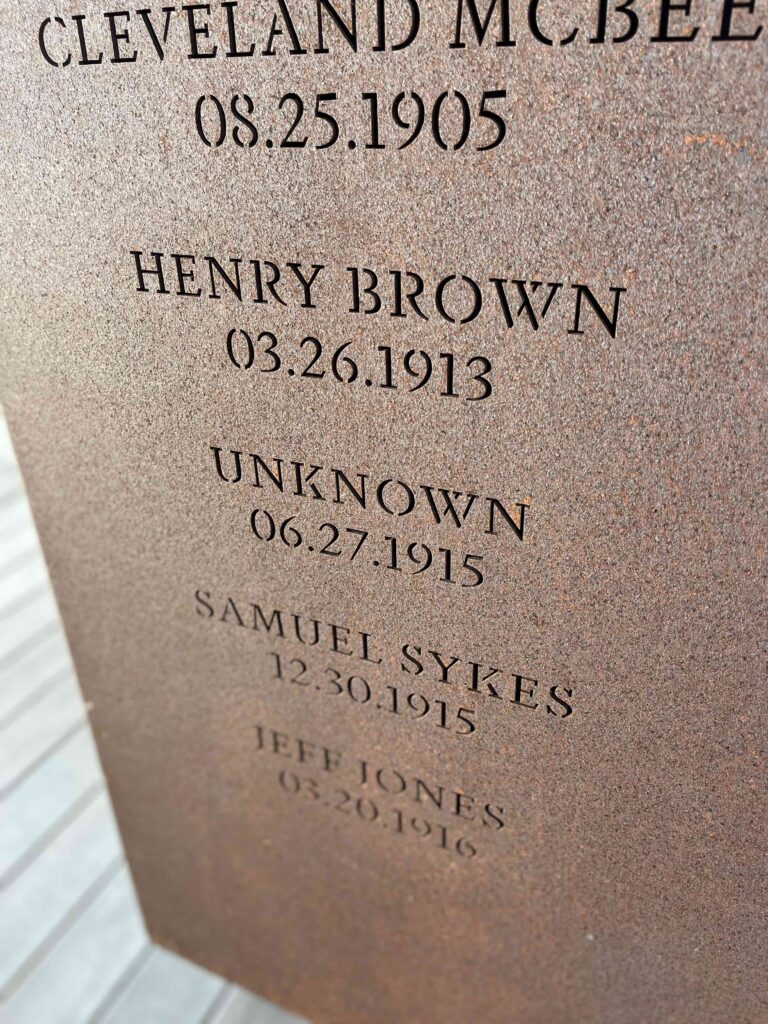

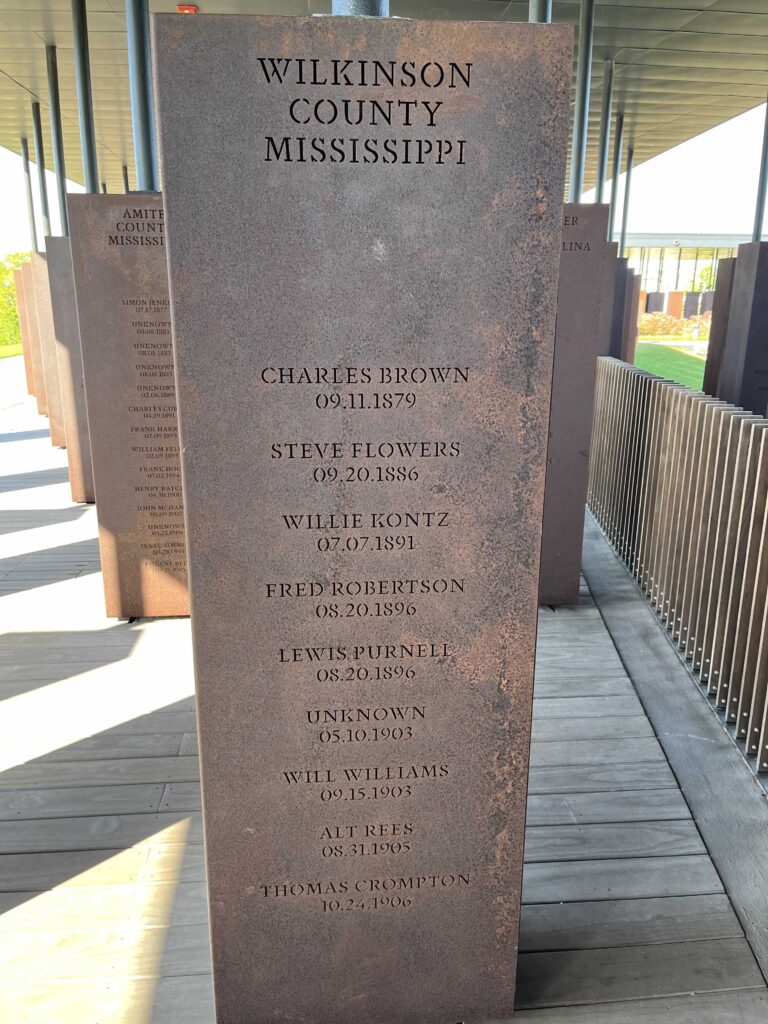

There are so many names. Too many names. Too many counties. Too many states. Too many lynchings.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the folks behind the Legacy Museum/Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, has documented thousands and thousands of lynchings of African Americans in this country. Primarily of Black men, the exhibit at the Museum also notes the accounts of 150 Black women and 100 accounts of Black children being lynched.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is an artistic, sacred recognition of these lynchings and the lived lives of those who died by this particularly pernicious, and particularly racialized, violence. The efforts of the staff of EJI include

“a project to memorialize this history by visiting hundreds of lynching sites, collecting soil, and erecting public markers, in an effort to reshape the cultural landscape with monuments and memorials that more truthfully and accurately reflect our history.”

https://museumandmemorial.eji.org/memorial

It is clarion clear that the staff of EJI have brought their all to make as real as possible the aspiration of the poet’s words:

Your names were never lost,

“Invocation” by elizabeth alexander

each name a holy word.

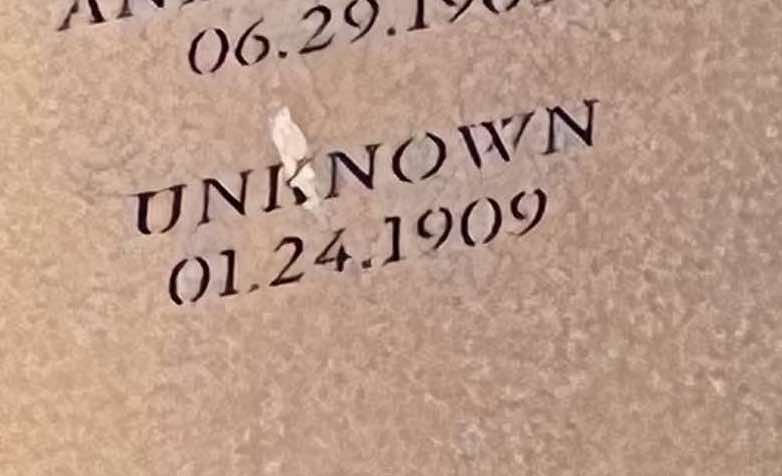

Yet my eyes kept finding this word.

My heart wept each time I encountered this word.

Over and over.

In the midst of terror and trauma, systematized cruelty and institutionalized murder, it is hard to think there is something worse that a life stolen by lynching, and the various forms of torture it entailed.

Then I see the fact of a lynching, and that word: Unknown.

It is known that someone was lynched, but it is unknown who it was who was lynched, whose life was stolen, whose loved ones wailed with outlandish pain. What is already a gut punch is even more so.

I think my eyes, my heart, my mind were drawn to the many “unknown” engravings on those more than 800 corten steel columns because the Lost Souls Public Memorial Project, of which I am a part, faces a similar dilemma.

At this time, the Project knows of 137 Black women, children, and men who were kidnapped, deceived, stolen into permanent slavery in 1818 by a statewide network, a slave ring headed by a corrupt county judge. We know first names and on some rare occasions, sir names. We know the supposed ages of most. In some cases, we know the nefarious details with which slavers occupied themselves: height, skin color, and sometimes other attributes.

However, in the case of 9 individuals, we know they existed. We know that they fell victim to this slave ring. But we do not know their names. Each is our “Unknown.”

At the end of every May, beginning in 2018, we have held a Recitation of Names, to honor these Lost Souls, to center their names rather than that of the corrupt judge, to bring reverence to the efforts to uncover this history, educate the community, and remember them. In that first year, we did not have yet a hundred names – it has been an unfolding process of research that has revealed the extent of the slave ring’s abominable enterprise.

In those years in which we have known about those nine, we have always been sure to create a space that holds them, even as we cannot speak their name. Typically, we ring a chime, once for each unknown Lost Soul – nine times altogether, interwoven with the spoken names of the 128 other Lost Souls. Names like

Harriet

Moses

Elizer

George Bryan

Betty, age 22

Nancy, and her son, Joseph, 2 days old

Peter

Yes, at the annual Recitation of Names (this year on May 22) we hold space for the Unknown Lost Souls. And. whenever it is the Project is successful in building the memorial, the vision will include space for all, whether we have their names or not.

It may well be that the prevailing narrative has tried to erase history, has tried to erase from our working memory any knowledge these people. Yet we resist. Yet we will not let that happen, particularly in the tragic case where we have lost the name: we will continue to hold space these Unknown Lost Souls.

For those who were lynched, and those who were stolen into permanent slavery, may these poet’s words from the conclusion of “Invocation” speak to you, for you, of you: