It had been suggested to me that I might want to consider taking one of the historical Paddlewheeler cruises that are offered in New Orleans. Given how essential to the slave trade the Mississippi River was, I thought there might be something worthwhile about this recommendation. So yesterday afternoon, I boarded the Queen Creole for a two-and-a-half hour cruise that included an hour tour of the Battlefield Chalmette.

Now, I didn’t do my homework ahead of time. I think because I was letting my Northern mind over-project, particularly with my focus on the experience of enslaved peoples. Because when I heard “battlefield” I immediately thought of the Civil War. I had wondered what monuments to the Confederacy I might see. I was getting pre-emptively ready to be disgusted and outraged.

But the Chalmette Battlefield, and the National Park it has become, is about what the United States calls the War of 1812. You know, the time the U.S. attacked Canada THREE times and was repelled all three times? The war in which we burned the city of York (what is today Toronto) and so the British came to this continent and in retribution, burned Washington DC (and the White House)?

I don’t know about you, but I did not learn about that war in high school. I first learned about our attack on Canada about a decade ago when I was visiting Halifax, Nova Scotia. The things they don’t teach us.

So, while the Chalmette Battlefield, and the National Park it has become, is explicitly about that war, I cannot go so far as to say it is not about the Civil War. Which is to say, I cannot go so far as to say that it’s not about what was at the heart of the Civil War: the slave economy.

But I had to ask. I had to know to ask. And once I did, what was always present, but occluded, was visible.

The Park Service guide/narrator and his co-worker dressed in period-clothing stood alongside a ditch as they convened a powder musket demonstration and described the battle, which took place in 1815. The tour guide said that because it was April 1st, he would tell the version of the story that was more- I don’t remember his exact words, but something like “fun.” So he spoke of the role of British soldiers drinking too much in Jamaica and revealing their plans to invade New Orleans, and how privateers then brought that news to New Orleans, which allowed the U.S. soldiers to be ready and not be surprised. I guess the light-heartedness is about getting drunk?

Sure. I get it. You tell the same story, day after day, you have to come up with new ways to tell it, to change it up. Happy April Fool’s Day! I guess.

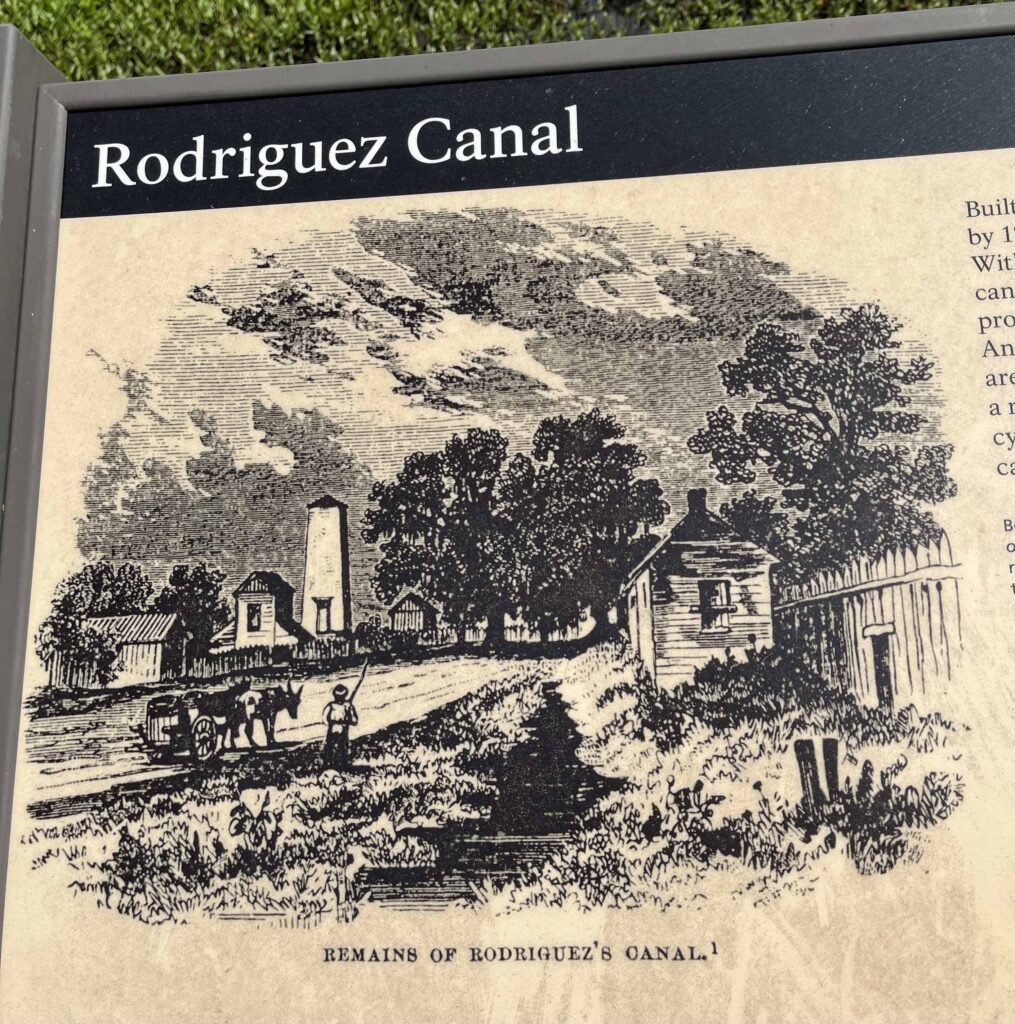

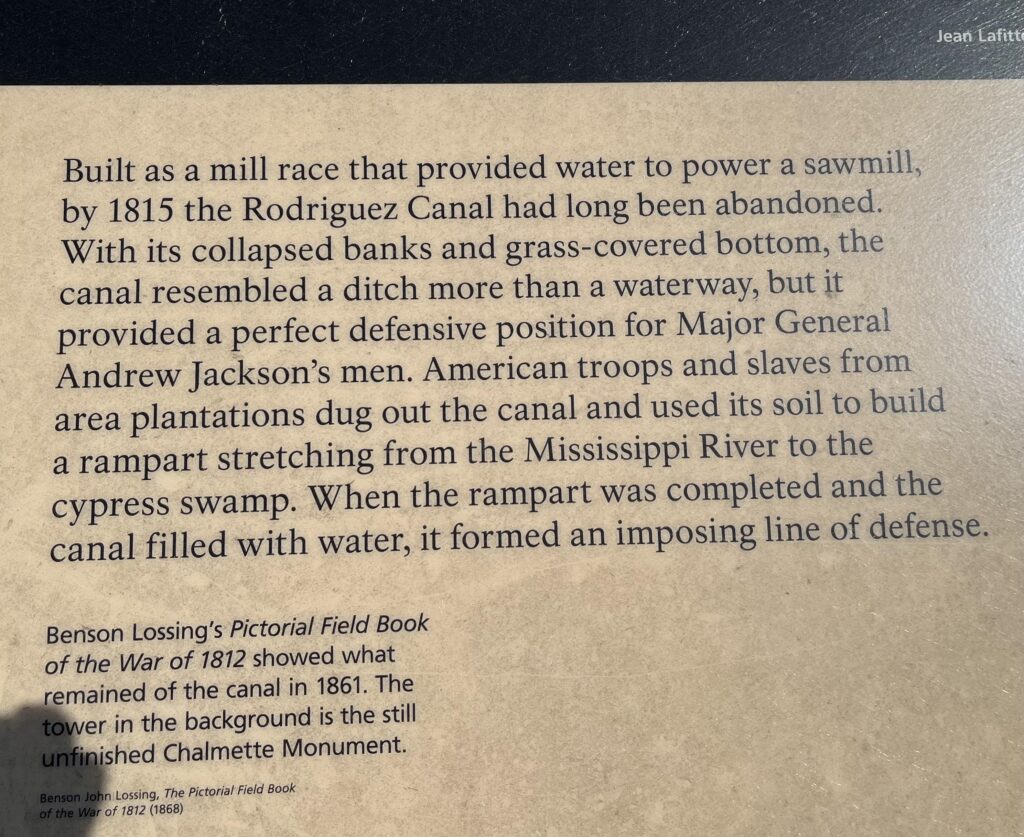

After the demonstration was done, I thought more about that ditch, the official name of which is the Rodriguez Canal. Apparently, it was a key strategy that allowed for the U.S. win over the British on that Battlefield, acting as a moat between the two armies, allowing the U.S. soldiers some protection as they reloaded their muskets. My mind began wonder about who dug that canal.

This was 1815. The slave economy is in full-tilt action. So after walking part of the park, I found the guide and I asked, “Who dug the canal?”

I knew to ask about who dug the canal because near where I live, in Central New Jersey, there is also a canal. The Delaware & Raritan Canal. I walk alongside it nearly daily with my dog. It was not dug by enslaved people. It was, however, dug at first by Irish workers. Who then caught cholera, many of whom died. And then, because of racist ideas of the Black body, Black laborers were brought to finish the job, because it was believed that they could not be sickened in the same way as white men (or at least Irish men, who at the time, were probably not yet considered fully white). Of course, those Black laborers also contracted cholera. They also died. (I don’t have a citation for this while I am traveling, but it’s in a book about local Somerset history at home.)

Stories of white supremacy are all around us, if we but ask.

The park service guide said that it was dug by a combination of soldiers and “enslaved persons on fatigue duty.” He talked about how the white slave holding soldiers had been skittish to bring their enslaved property to the battlefield, because in 1811 there had been a local slave revolt, and they did not want to provide opportunity for the enslaved to communicate amongst themselves. The implication was that there were not that many enslaved persons working the battlefield.

Well. That led to two follow-up questions. The first one: What is fatigue duty? His answer was a long list of activities that ended with the summation of basically anything that was expected of a soldier that wasn’t outright fighting the enemy. Which certainly makes it sound like the assignment for enslaved people was to do all the hard labor, as the course of things. I don’t know. I just suspect.

My second question was, Why didn’t you tell that story when we were all listening? His response was, implying that he had made a change from his normal course of action, he said because it was April Fools and he wanted to lightened up the story. I don’t know. I hope so. I hope that he regularly tells the story of how enslaved people are a part of the history of which he is an official steward, employed by our federal government to tell the whole story.

He said his goal was to lighten things up. If we think about lightening things up not as injecting humor or light-heartedness into a moment, but as lightening or white-washing a thing, then he certainly achieved it.

Happy April Fools Day?