How might we surrender to our place in the vast cosmos, the strange mix that does not reveal the depths and breadths of its true nature to mere mortals such as we are, yet begs us choose to see angels and generosity, beloveds in the midst of the unknown, and life singing its song of creation?

Possible Angels and Miracles

This is the angel I met today. Her name is Venita Halbert. Her official title is Community Liaison at the Emmett Till Interpretive Center. She was thoughtful, friendly, and informative. While I learned about the trial of Emmett Till’s murderers from the exhibit, and Venita answered questions that I had, I learned about the local community from her. She says the tour she gave me today was one of her first. I think she’s a born-natural – at welcoming and informing, as well as at community organizing.

I likely met other angels today.

Like Johnny B. Thomas, founder of the Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center/ETHIC and mayor of Glendora. We had a brief conversation as I was leaving the museum. He shared with me how he had just returned from having been in Washington, DC to be present for President Biden signing into law the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act that was 124 years in the making, making it a federal hate crime.

124 years. Shameful.

I didn’t get a photo of the mayor, though there are some on the web. I like this one in particular. Or this one. I have only this image of the outside of the ETHIC because even though what is inside is quite compelling, the rule is no photography.

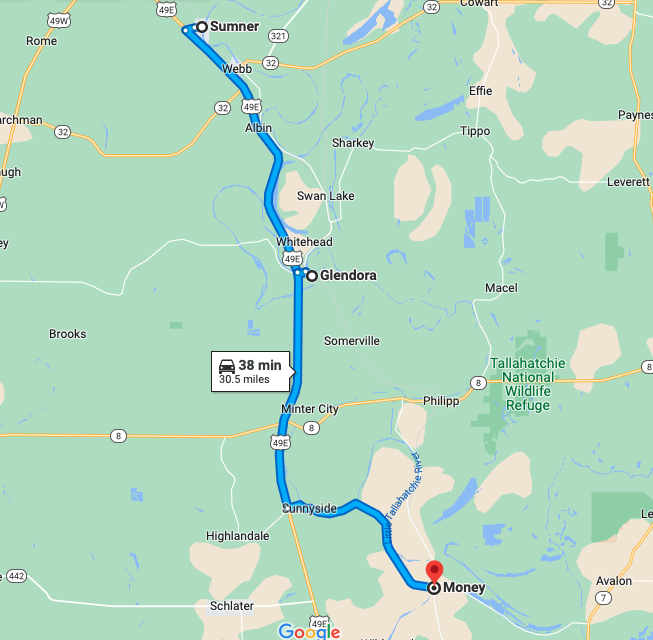

Sumner and Glendora are close to each other (about a fifteen-minute drive), but are two different communities. Each has a different connection to the Emmett Till murder. Money, MS, is another community with a connection; it is still further South. Here’s a map:

The town of Money is where Emmett Till (who was visiting from Chicago) was staying with his uncle, Mose Wright. It was from this family home that the 14-year-old was snatched in the middle of the night by three white men, who then tortured and murdered the child, coercing several African American men to assist, weighting his body down with a 74-pound industrial fan, then dumping him in the nearby river.

Glendora’s connection to the murder is harder to trace. The ETHIC museum claims that Till’s body was dumped from the Black Bayou Bridge, which is in Glendora. Apparently, there is no consensus on this. What is known is the site where his body was discovered, along the banks of the Tallahatchie River, but not in Glendora. So, while the contemporary connection to Glendora might be murky like the nearby river, the modern connection is the ETHIC museum, which is a combination of history, education, call to bear witness, and call to change injustice. On one of the walls in the museum this is spelled out in tall letters:

PROMOTE HUMAN RIGHTS, PREVENT HUMAN WRONGS

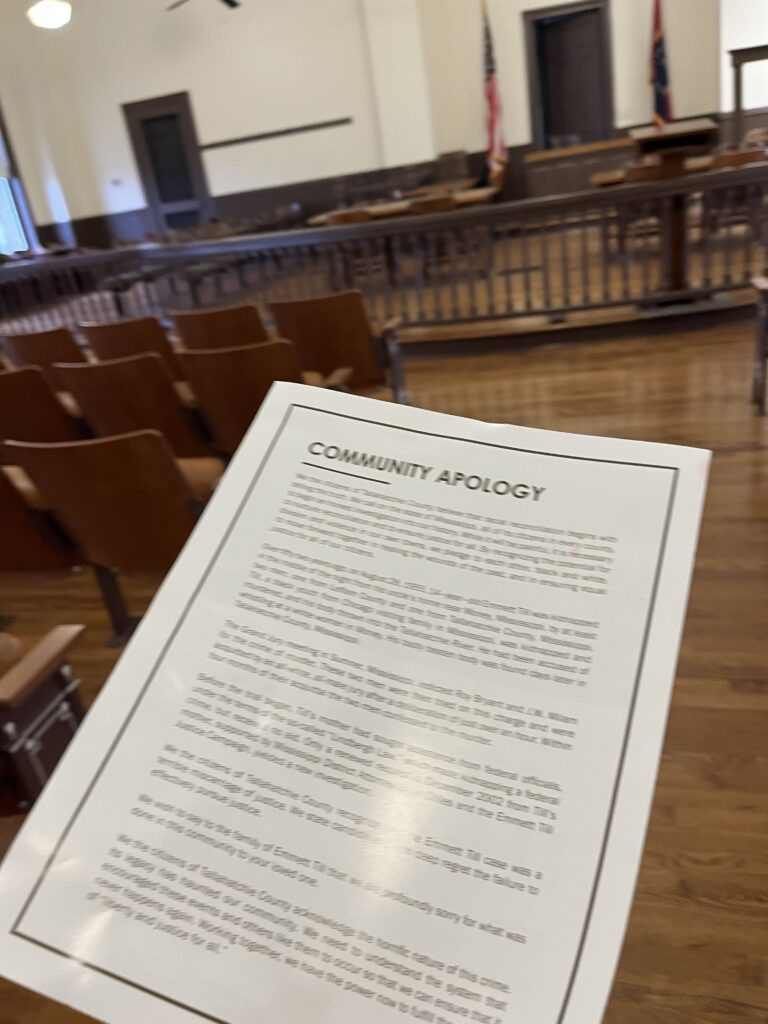

Sumner is where the trial of the two white men (only two, though a third was involved) ~ Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam ~ was held, demonstrating excesses of white supremacy which ultimately won the day. Both men were found not guilty in a matter of 67 minutes by the all-white, all-male jury. Just a few years later, these men sold their story to a magazine. In that interview, they confessed, protected by the double jeopardy clause in the 5th amendment. They could not be tried again. Justice was never served.

There’s an interesting video about the courthouse that the Emmett Till Interpretive Center put together – the attention the trial brought to this sleepy town, the strong desire for amnesia after the media went away, the remodeling of the courtroom that can be understood as a form of erasing painful cultural memory.

Then, based on the efforts of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission established by the Tallahatchie County Board of Supervisors in the early 2000s, a realized effort to return the courtroom to its original appearance, shifting “the primary narrative of the courthouse. It was no longer about architecture; it was about race, memory, and justice.” It’s a compelling way to understand the process of surfacing a memorial in an already-existing space.

Another outcome of the Till Commission was an official apology to the Till family in 2007. You can read the text of the apology here.

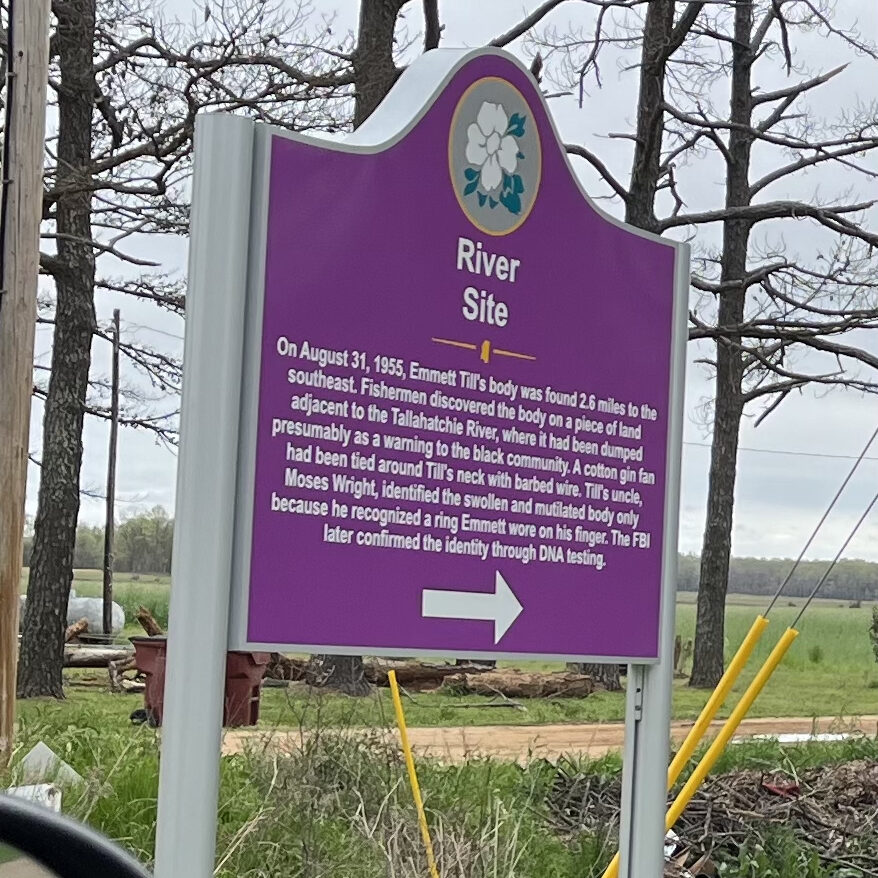

After visiting the two centers, I drove to the spot where Till’s body was found. It’s two-and-a-half miles down an isolated, dirt road. My angel from the first center had recommended against my going because the river had been high lately. Cautiously, I went anyway. The rain had stopped. The river, while brown, was not wild or near the top of its banks.

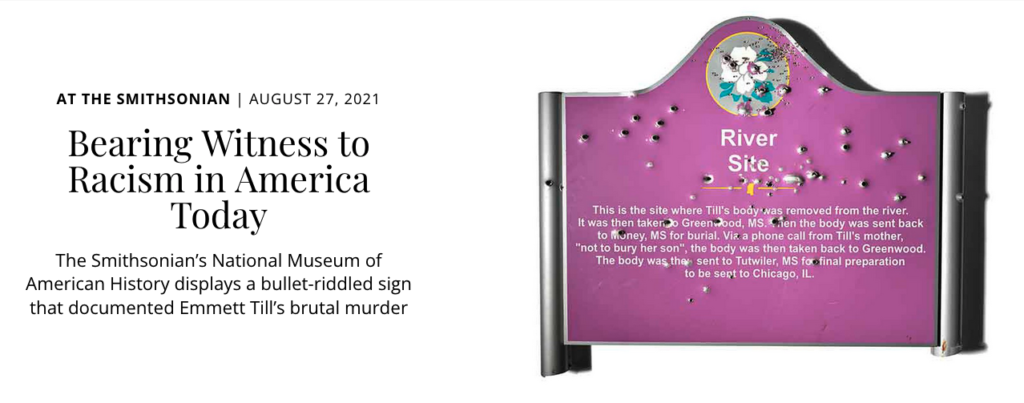

The sign at this site has gotten a fair amount of media attention, largely because previous signs have been vandalized. By which I mean, they have been shot at, excessively and violently. Several signs have been erected, only to be replaced because of the vandalism. The most atrocious example of vandalism is this sign, which has been formally inducted into the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

The current sign, installed in the fall of 2019, is bullet-proof. It also has surveillance cameras. Which proved useful not long after this version of the sign was installed, as a group of white nationalists showed up and tried to make a propaganda film in front of the sign. Using the surveillance camera, the Interpretive Center was able to notice them and set off an alarm that scared them away.

As is rightful, the sign has become a sort of shrine. Like other sites of violence, or tragedy, or injustice, at the base of the sign, people have left objects as a gesture of respect, a sign of lamentation, a signal of solidarity.

There were plastic flowers. There were two items that said Black Lives Matter: a face mask and an earring. I, too, offered my witness, pouring some of the doubly-blessed homegrown holy water I have brought along on this journey.

I walked to the edge of the river – not too close, but close enough. It was quiet, with only the sound of the moving water and some songbirds. It was muddy, the earth beneath my feet soaked so much so that each time I picked up my foot, there was resistance and a sucking sound. I had to steady myself several times because it was slippery. I tried to make sense of natural beauty of the riverbank; the stillness with its peaceful quality; the sense of danger from the slippery, sucking mud; the haunting echo of historic violence; and the distressing presence of deep poverty of that region.

It’s wrong to use the past tense. I am trying to make sense of all these. I will be trying. It will take a lifetime. And more. Thank All That Is that there are angels in the world to help.

If you don’t know the story of what happened to Emmett Till in 1955, it’s about time you learned. Here’s a good place to start.