When I was a kid, I had such a hankering for salt that I would steal my dog’s salt lick. I know: that sounds if not disgusting, super unhygienic. Even to me. I’m not sure why my dog had a salt lick – maybe that was a thing in the 1970s?

Also, in the years we had a machine for making homemade ice cream that required rock salt, I would sneak into our pantry and take a handful of those white, semi-transparent crystals. I’d bring them into my bedroom and suck on them for days. (Yes, I was a weird kid.)

So, when I learned that the geology of Avery Island was a dome of salt rock, and this is what makes it a land island (though it is surrounded by bayou, salt marsh, and swampland), my interest in going was doubled.

The original reason I was drawn to Avery Island is that it seems connected to the destination of at least six of the Lost Souls. Now I use the word “seem” intentionally here. While there is support for this theory, which I am about to share, I am also aware that the public historian for the Lost Souls Public Memorial Project has not verified this theory. And until she does, a set of insufficiently-connected dots it remains.

Connecting The Dots

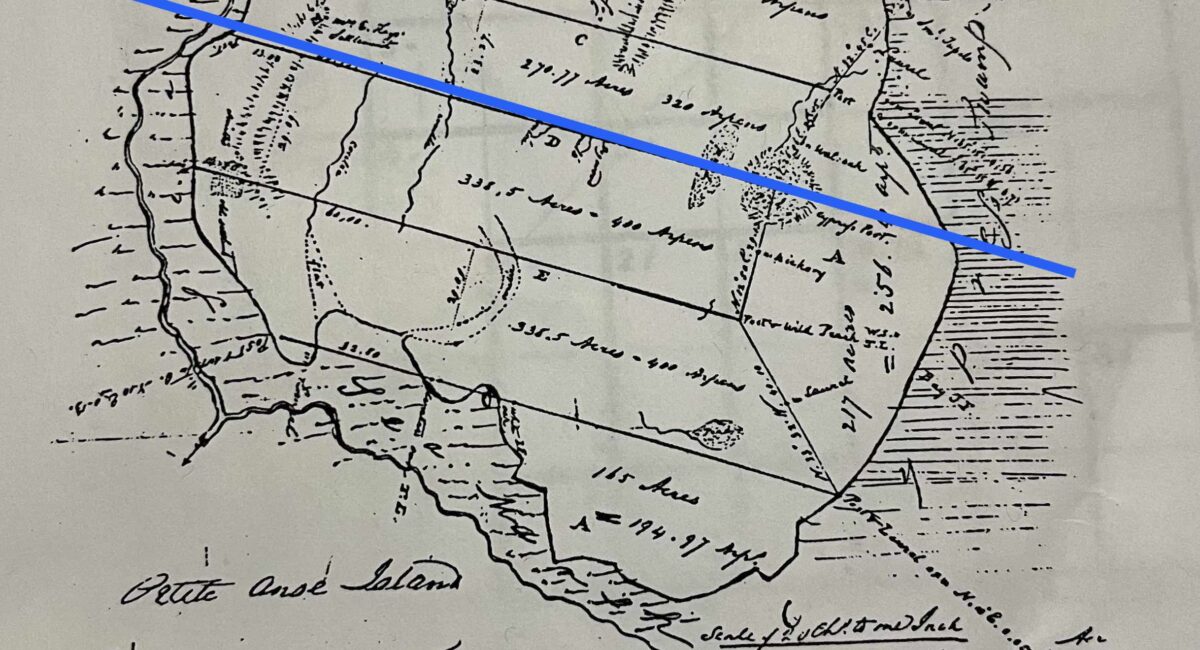

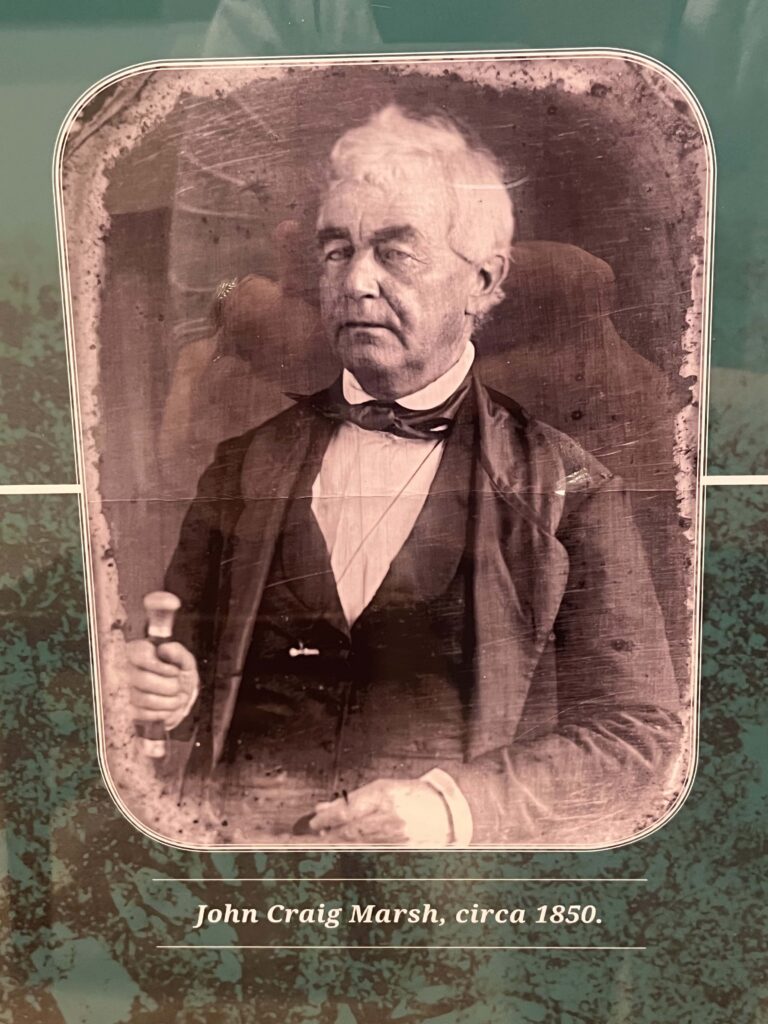

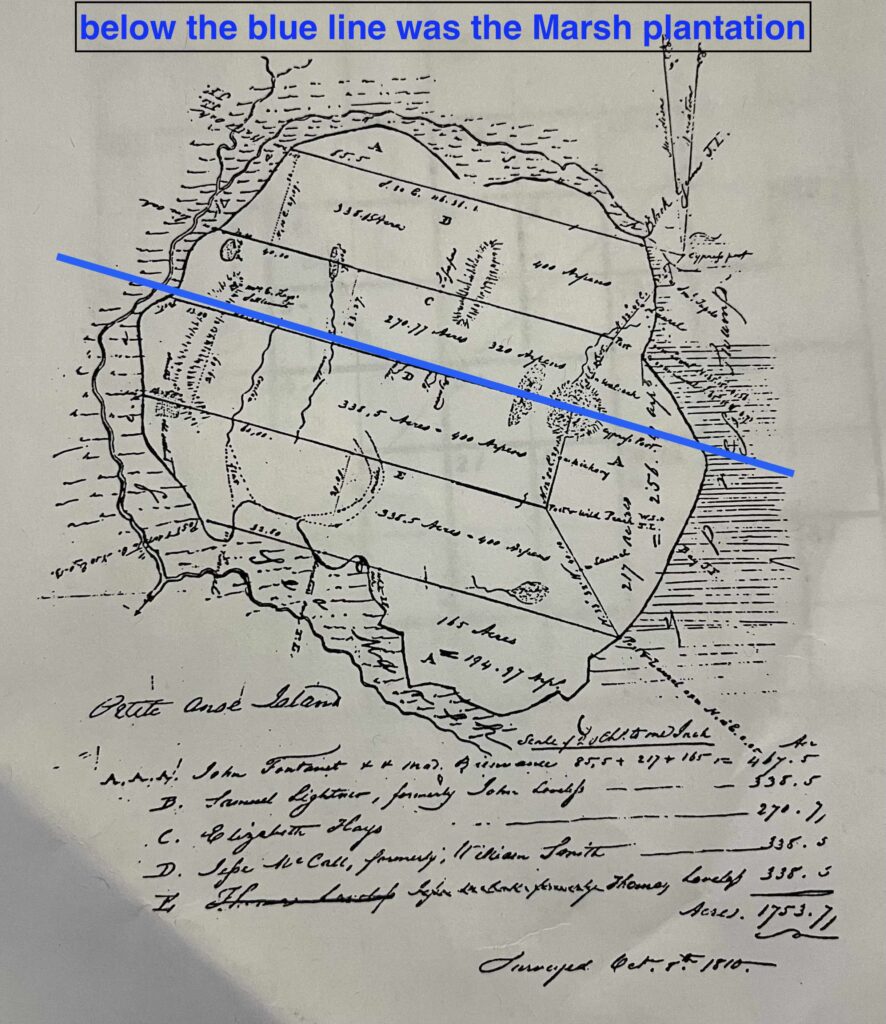

John Craig Marsh was originally from Rahway, New Jersey. In 1818, he came to Louisiana and purchased half of what is now Avery Island. He turned his purchased land into a plantation which named Petite Anse. Though salt had been harvested from the briny water for millennia (first by the indigenous peoples, then by Europeans and their enslaved labor), the plantation’s primary crop was sugar cane. Eventually, Marsh’s daughter married into the Avery family and, several generations later, the area became known by the name it carries today.

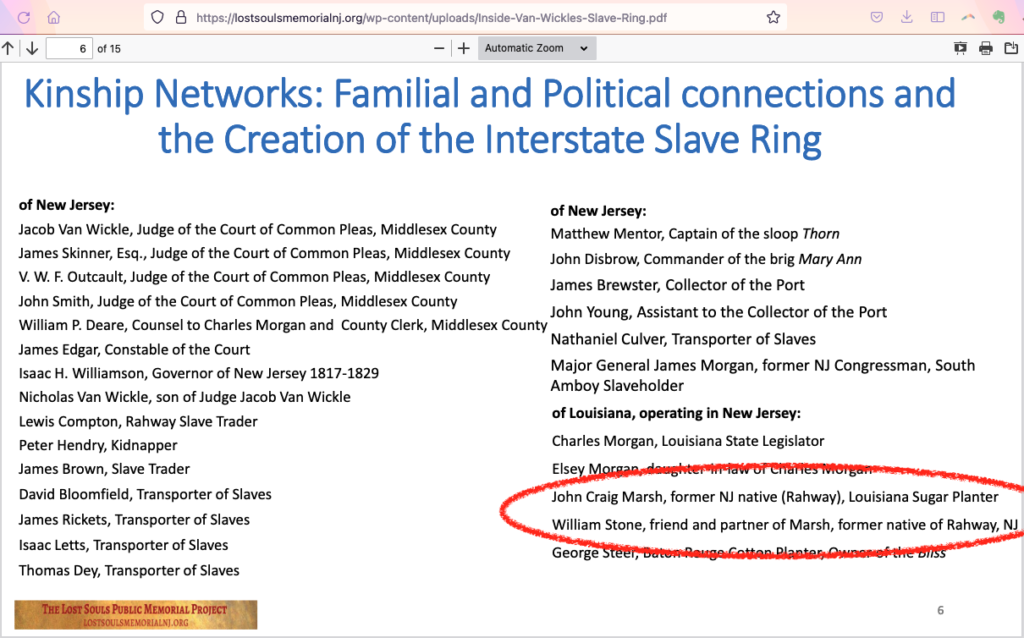

In the early part of the 19th century ~ in 1818 to be specific ~ Marsh worked with a man named William Stone and has been implicated in the Van Wickle Slave Ring, using Lewis Compton, a known slaver in the New York/New Jersey area, to acquire labor for his Louisiana plantation.

I understand that Marsh brought others of African descent from the New York area down to the Petite Anse plantation. In addition, the Lost Souls Project’s historian has confirmed that six individuals were brought by Marsh and Stone before Judge Van Wickle to establish the ignominious legal authorization to bring them down South, purportedly as indentured servants. It is these six individuals who are among the 137 Lost Souls that the Project is working to remember and honor.

Purportedly as indentured servants. What does that mean? This is the perverse and contorted aspect of New Jersey law that made some aspects of the Van Wickle slave ring legal. The law that brought about gradual abolition in New Jersey in 1804, re-affirmed in 1812, allowed for an individual to give consent to be brought to the South.

Who gives consent to be sent down to the Deep South, to some of the harshest agricultural conditions where enslaved peoples quality of life was already substandard and their average life span was significantly curtailed because of the working conditions demanded and imposed on sugar plantations?

- people who are either not fully informed;

- people who are explicitly deceived;

- people who do not have full capacity for consent because they are enslaved.

That’s who.

We have no proof that the time-limited period of indentured servitude supposedly offered to some of the Lost Souls and written into some of the certificates of removal was honored once they arrived in Louisiana, a state solidly committed to the enslavement of (most) African-descended people.

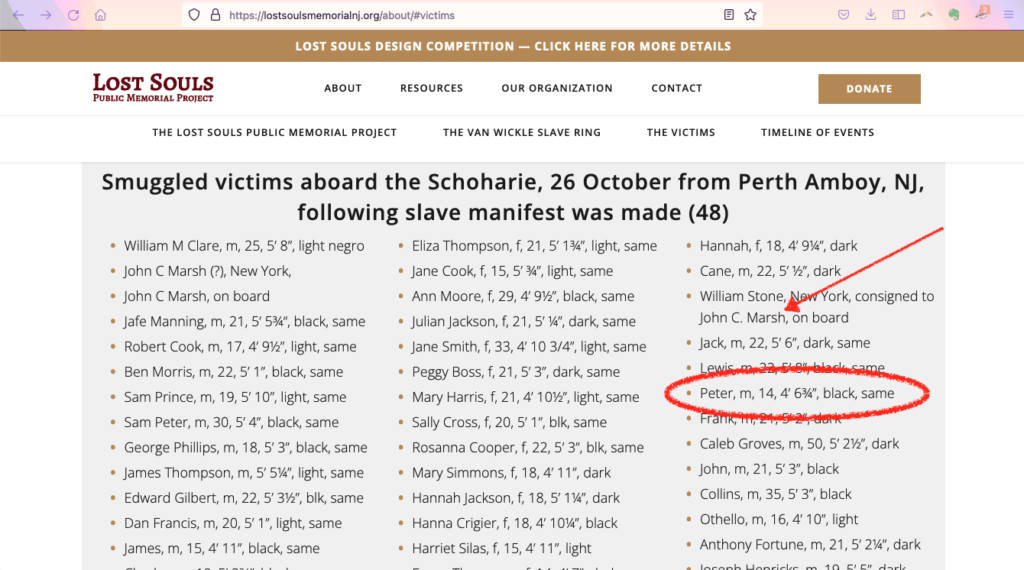

The Lost Souls Project public historian confirmed to me that those six individuals, brought before Van Wickle by Marsh and Stone were put on the Schoharie, a boat that sailed from Perth Amboy on October 26, 1818 with other Lost Souls. The Project has not yet verified that once they arrived in New Orleans what their final destination was.

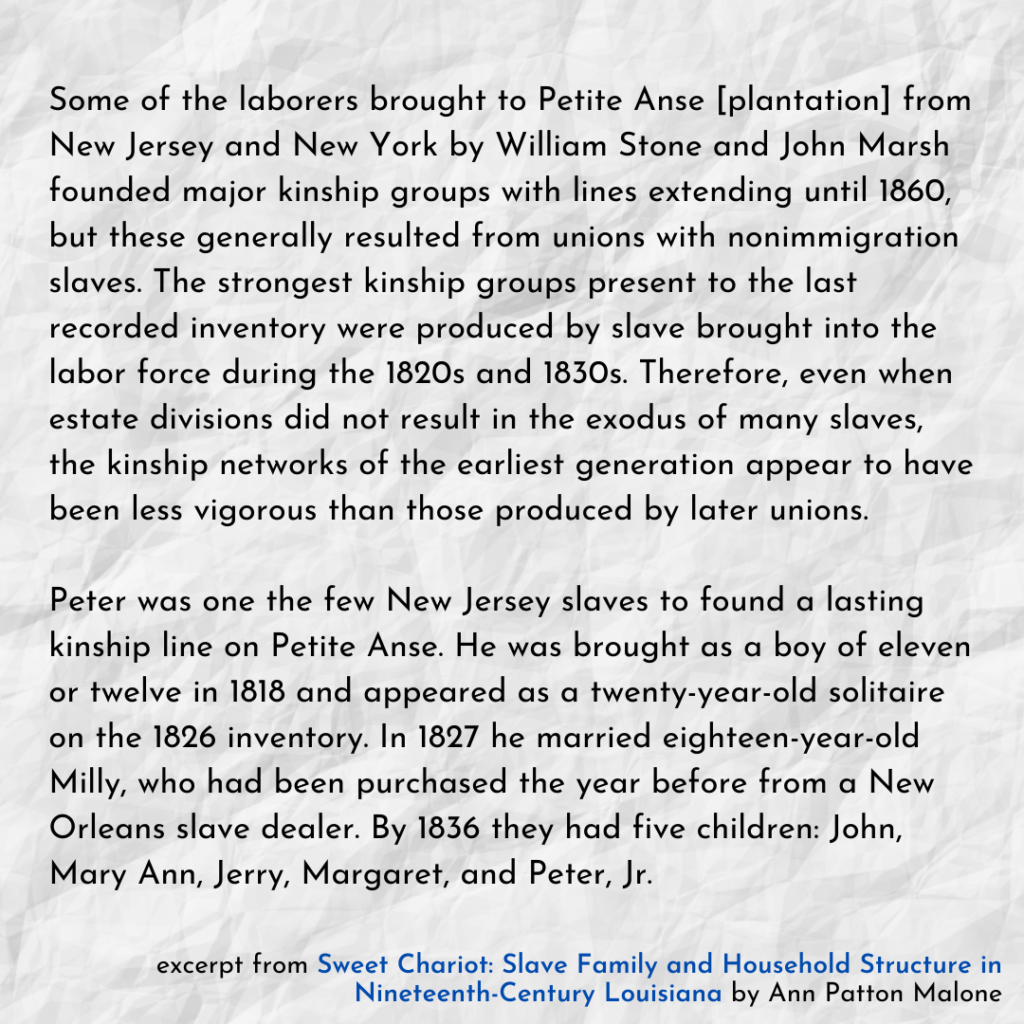

And this is where I turn to the research of Ann Patton Malone, from her book, Sweet Chariot: Slave Family and Household Structure in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana, published in 1992. In it she writes,

Is this the same Peter? The one mentioned in the manifest of the Schoharie? It has not been verified. But I think it not irresponsible to attempt to connect dots as long as I am being transparent about this conjecture. Let me try.

There is a Peter was on the Schoharie manifest. Peter is listed as 14-years-old. Notice the height attributed to him: 4’ 6 ¾”. That is small for a 14-year-old. Plus, in these certificates of removal and ship manifests, there were an over-abundance of 14-year-olds, especially ones short for that particularly age. It has been suggested that some of the ages of these kidnapped souls were overstated.

I have wondered, and sometimes speculate, that 14 was considered the age of consent and likely assigned to those kidnapped or sold to fit within the letter of that strange New Jersey law that said people of African descent could be sent down South with their consent. It is possible that the Peter listed as 14-years-old on the Schoharie manifest was actually younger AND is the same Peter who arrived on the Petite Anse plantation in the same year – 1818 – and became the patriarch of a robust multi-generational family described in the Sweet Chariot book.

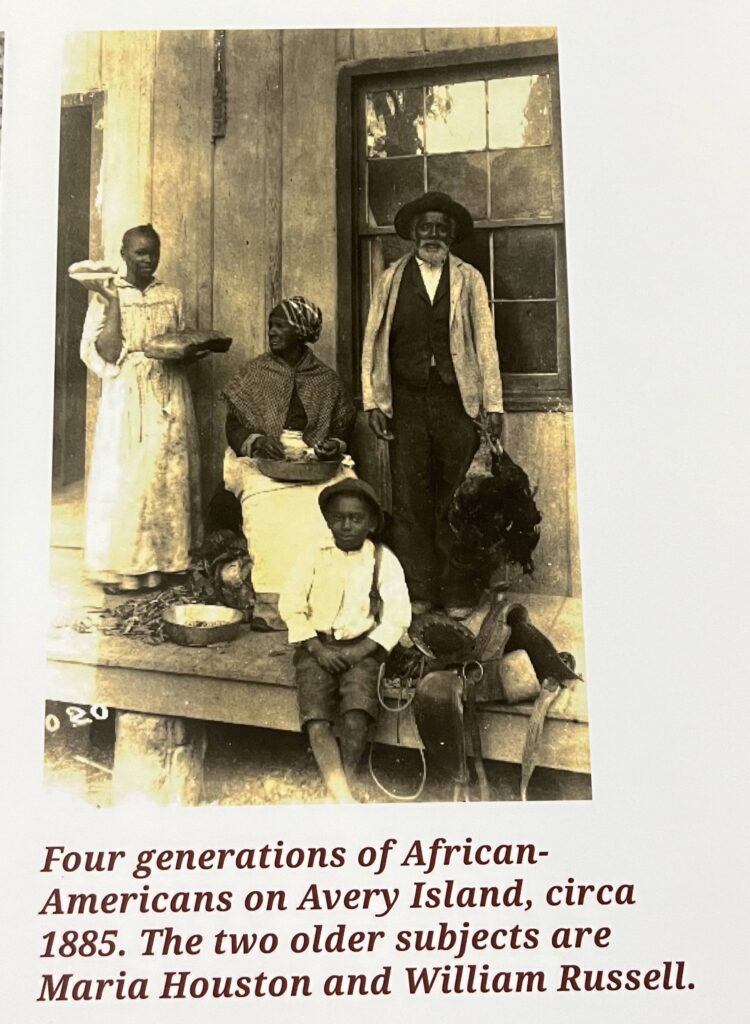

This is not a photo of Peter and his family. It is, however, a photo (circa 1885) from the Tabasco Museum on Avery Island of a four-generation family who lived and worked on Avery Island. This family is headed by William Russell and includes Maria Houston, likely his daughter or wife of his son.

And while it is not Peter and his family (as described in the Sweet Chariot book), this image probably comes pretty darn close to what they might have looked like in 1885.

I don’t know how old William is in this photo. Given the harsh conditions under which enslaved people had to labor, they must have aged quickly. So, what might look like someone who is 60 or 70 to my modern eye could well be only 45 or 50. If he is on the older side, he’s not that much younger that Peter would have been.

Since the photo is 1885, the youngest person in this photo (unnamed) did not directly experience slavery. And possibly his unnamed mother did not, as well, or she might have been born enslaved and then set free. Yet the two older, named individuals in this photo, experienced enslavement and most likely, on Avery Island and possibly as part of the Petite Anse plantation. (While I was in Louisiana I learned that it was common for formerly enslaved people to stay working on the plantations where they had previously been enslaved, as opportunities for leaving were few and white people, especially the land-owning ones, still very much exercised economic and legal controls over the lives of African Americans.)

It is the possibility of a connection to the Lost Souls that led me to Avery Island on this pilgrimage. To Avery Island, a possible, even likely, destination of at least six of the Lost Souls. To Avery Island, where I was warmly welcomed by Shane K. Bernard, Curator of the Avery Island Archives, with whom I corresponded in the weeks ahead of this trip.

Once on island, Mr. Bernard was generous with his time, taking me on a tour of the island, answering my questions not only about the origins of the Petite Anse plantation, but also about the salt dome.

(He did not give me any rock salt; then again, I did not tell him of my childhood predilections.)

Mr. Bernard already knew that John Craig Marsh, in establishing the Petite Anse plantation in 1818, had brought several Black “indentured servants” from New Jersey. Mr. Bernard had seen the certificates of removal in the Marsh Family archives. He encouraged me, or the Lost Souls Project, to access the Marsh Family papers which are available through interlibrary loan to those with academic credentials. The Marsh family, after donating the papers, in the following generation asked for their return; the originals are now a part of the Avery Island Archive.

Mr. Bernard encouraged me to visit the Tabasco Museum. I’m so glad he did, as I found the photo of John Marsh as he said I would. (I also found a disappointingly white-washed history of Avery Island that makes no, or only rare, reference to slavery. Which is just absurd. And disappointing. And outrageous.)

So while I was there, being sure to do it on land that had belonged at one time to Marsh (he owned the Southern half of the island, which is what made up Petite Anse plantation), I poured libation for all the Lost Souls. I recited the names not of the six Marsh brought here (I do not know for sure which six of the Lost Souls he brought, though I believe that it is in the process of being established), but ten names of the Lost Souls, hoping that would be something.

I walked into a tiny clearing, not that far from a stand of Live Oak trees. I crouched next to a palmetto and hoped for no snakes. With each name, I let water fall to the ground, recognizing the lives of the Lost Souls, the harm done to them when their liberty and chance at freedom was stolen from them. I let this homegrown holy water, doubly blessed, fall to the ground that the efforts made on their behalf, these two centuries later, generate merit and bring healing through truth-telling.