The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

December 5, 2021

Reverend Karen G. Johnston

This video contains the spoken version of this sermon.

Part I

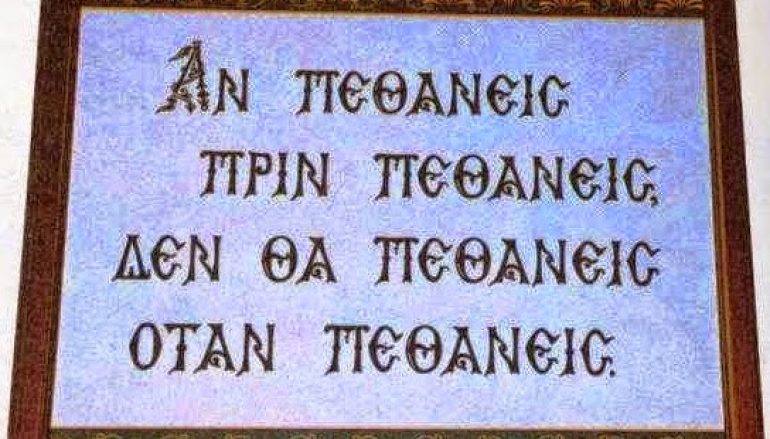

If you die before you die, then you won’t die when you die.

This is an inscription over a door at a monastery on Mt. Athos in Greece. I’m asking you to keep it in mind as you listen to my sermon.

If you die before you die, then you won’t die when you die.

This sermon on mind-manifesting plant medicine – that’s what “psyche-delic” means: mind-manifesting.This is not meant to be…trippy, though I suppose it might sound like it to some ears. Maybe it is trippy. But it is also true, as the new science about psychedelics tell us.

If you die before you die, then you won’t die when you die.

It is a different phrase than turn on, tune in, drop out – a phrase made famous by Timothy Leary in the 1960s. If what you know about psychedelic drugs comes from that era, it is time to catch up. There are great things afoot in the world of psychedelics. It’s important that we know about them. It’s important that we put aside out-of-date notions because it may mean we can reduce the suffering of others, of those we love, and even our own.

Important because recent science is showing that substances we commonly refer to as psychedelics have the power to heal some of the most intractable scourges facing modern humanity: addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder, treatment-resistant depression, death anxiety in those with terminal diagnoses (as we saw in the video earlier), even debilitating despair in the face of climate collapse and the potential for human extinction.

Indigenous cultures around the world have been in relationship with plant medicine, sometimes called plant wisdom, since our species emerged. Use of Peyote (sometimes called mescaline), a desert cactus with natural hallucinogens, dates back as far as 5,700 years. In fact, there are suggestions that our hominin ancestors ingested psychedelic mushrooms as a matter of course. In some traditions, the source of the mind-altering experiences is understood to have sentience and be an intelligence in its own right. So, the relationship between entheogens and human is ancient, but is not just ancient. It exists today and we owe gratitude and recognition to indigenous communities here in the Americas and on nearly every continent.

Hold up. Stop. Entheogens? What’s that?

Entheogen. Derived from Greek roots: en (within) theo (divine) and gen (creates). Its literal meaning: “creating the divine within.” It’s an alternative term to “psychedelics” that may have been irreparably tainted by both the high recreation time of the 1960s and the Nixon- and Reagan-era dragnet wars on drugs.

It also points us beyond the mind to the transcendent qualities of these substances and their long-existing use in religious and spiritual rituals and practices.

It’s not just spiritual types who are using that term. In 2019, the City of Oakland decriminalized specific entheogenic plants. There is a growing movement throughout the country called “Decriminalize Nature.” Multiple municipalities are passing resolutions that decriminalize some of these substances: not just Oakland but also Denver; Washington D.C.; Seattle; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and at least four cities in Massachusetts. Decriminalizing a thing does not make it legal; it means that it is the lowest priority for law enforcement.

The state of Oregon has gone even further, passing Measure 109 in November, 2020, which created a two-year window during which the state would create a system that “allows manufacture, delivery, administration of psilocybin at supervised, licensed facilities.” This creates a state-sanctioned system that recognizes what the new science has been finding: many of the psychedelic substances have deeply healing properties that can address otherwise intractable conditions. Oregon has gone the furthest in this regard, but Hawaii, Florida, and even Connecticut are exploring the possibilities of medicinal uses of psilocybin.

Psilocybin. Another psychedelic word. It’s like today’s sermon is a dictionary of new terms for some of us. Psilocybin is the psychoactive element in what is often referred to as “magic mushrooms.”

Part II

If you are like me and grew up in the shadow of the war on drugs, you might find it hard to believe there was a time in our nation when psychedelics were not illegal. But it’s true. In 1954, Aldous Huxley published his book, Doors of Perception, about his experience with mescaline taken under the supervision of the psychiatrist who coined the word, “psychedelic.” LSD was viewed by some psychiatrists as a “useful adjunct to psychotherapy.” Bill W, considered the father of Alcoholics Anonymous, participated in an LSD session at the VA in Los Angeles in 1956 and came to believe the insights gained could help alcoholics with recovery.

The new science is proving him right.

In 1957, Life Magazine published an article that related the trip of a U.S. banker to the Oaxaca region of Mexico, where he was invited to participate in a religious ritual led by a Curandera, or healer, named Maria Sabina, who was one of many Curanderas, who was one of many in a long line stretching back centuries and perhaps millennia. Unfortunately, doing what white Europeans have been doing for centuries, that banker returned to the States and acted as if – or was treated as such that – he “discovered” magic mushrooms.

Lest I need to remind or inform you: Life Magazine was not some marginal publication. Its circulation was among the mainstream in America. That article was a big deal.

Scientists in the U.S. and Europe, perhaps elsewhere, had been researching the impact of hallucinogenic substances. As author Merlin Sheldrake notes in his book, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape our Future:

…recent findings have broadly confirmed the opinions of many researchers in the 1950s and ’60s, who came to regard LSD and psilocybin as miracle cures for a wide range of psychiatric conditions. In another sense, however, much of the research that has taken place in modern scientific contexts broadly confirms what is well-known to the traditional cultures who have used psychoactive plants and fungi as medicines and psycho-spiritual tools for an unknowably long time. From this point of view, modern science is simply catching up.

Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape our Future

And catching up, we are. In the past two decades, much of the published research on this topic has come out of Johns Hopkins primarily, as well as NYU and some from UCLA. Just a couple of examples from the new science:

- In a small double-blind study published in 2016, Johns Hopkins researchers reported that a substantial majority of people suffering cancer-related anxiety or depression found considerable relief for up to six months from a single large dose of psilocybin.

- A few years earlier, in 2014, also at Johns Hopkins, there was a small clinical trial addressing tobacco cigarette addiction. It combined the ingestion of psilocybin in a clinical setting with targeted cognitive behavioral treatment. Findings were extremely promising: after 6 months, 80% of the study participants had stopped smoking. After 2 ½ years, 60% were still not smoking. So promising that just this past October, Johns Hopkins announced that they were awarded a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to lead a multi-side, three-year study on the potential impacts of psilocybin on tobacco addiction (the other partner in this study are NYC and the University of Alabama). This is the first NIH grant awarded in over a half century to directly investigate the therapeutic effects of a classic psychedelic.

Out there right now are proposals to run clinical trials to treat professional burnout of health care workers in the context of the pandemic – just waiting for official approval. In April of this year, Rick Perry, former Republican governor of Texas, threw his political weight in support of access to psilocybin to treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in veterans. Beyond clinical trials, in 2019 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a ketamine-derived nasal spray to treat intractable depression.

What makes these plant or fungi-based medicines, or even the synthesized versions, so powerful? With the access to modern technologies not available mid-century, it appears that psychedelic substances work by inhibiting that part of our brain called the Default Mode Network. This is the part of the brain where our sense of self – what some might call our ego – resides. Psychedelics, or entheogens, by temporarily disabling the Default Mode Network, dissolve the separate sense of self, allowing the for new relationship with reality. Some describe it as experiencing the death of our ego.

If you die before you die, then you won’t die when you die.

Or as Dr. Matthew Johnson, psychologist in the psychiatry department at Johns Hopkins and lead researcher on that tobacco addiction study, describes it:

Psilocybin [and other psychedelics] “dope-slap people out of their story. It’s literally a reboot of the system… Psychedelics open a window of mental flexibility in which people can let go of the mental models we use to organize reality.”

quoted in Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life

This means that rigid conditions (like addiction or depression) or rigid attachments (like fear of dying or debilitating anxiety) become more pliable, opening to new cognitive – and some would say, spiritual — possibilities.

Just last month, the New York Times reported on the surprising presence of veterans lobbying for the legalization of psychedelic drugs. They interviewed veteran Jose Martinez, who said this: “I will not be told no on something that prevents human beings from killing themselves.”

Wouldn’t it be amazing if the astronomical rate of suicide in the military could be curbed with access to this plant medicine? Wouldn’t it be amazing if veterans, because they experienced the ego-death from a supervised psilocybin-assisted therapeutic session, didn’t find themselves compelled to experience body-death by suicide?

If you die before you die, then you won’t have to die by your own hand.

Some say it’s purely physiological or chemical. It clearly has psychological consequences. And some say that is not just those things, but can also be a religious, spiritual, or transcendent experience. Not a guaranteed experience of transcendence, but the possibility of it.

When one experiences the dissolution of self, of ego, and becomes one with the rest of reality, or discovers that one has been an interdependent part of all existence all along, it’s easy to understand why this might fit into our understanding of a spiritual or religious experience.

If you die before you die, then you won’t die when you die.

In those clinical trials involving terminally ill cancer patients, like the ones we met in the earlier video, it was those who had the strongest mystical experiences who showed the most effective results. The study noted that participants experienced reduced “demoralization and hopelessness, improved spiritual well-being, and increased quality of life.” When asked to describe these mystical experiences, participants described “a movement from feelings of separateness to interconnectedness” and “exalted feelings” of bliss, love, and joy. (Sheldrake)

Bliss. Love. Joy. Which just so happens to be our Soul Matters theme for the month: opening to joy.

Part III

If you die before you die, then you won’t die when you die.

Is this true? If you experience ego-death before you experience body-death, will you not die when you die? Or at least die with a bit more ease?

I guess this is the question I chase in my spiritual practice of befriending death. Can my meditation practice help me to face my own mortality? Can Date with Death Club help me and those who attend the monthly sessions practice welcoming the truth of mortality so that we are better at it when mortality comes knocking?

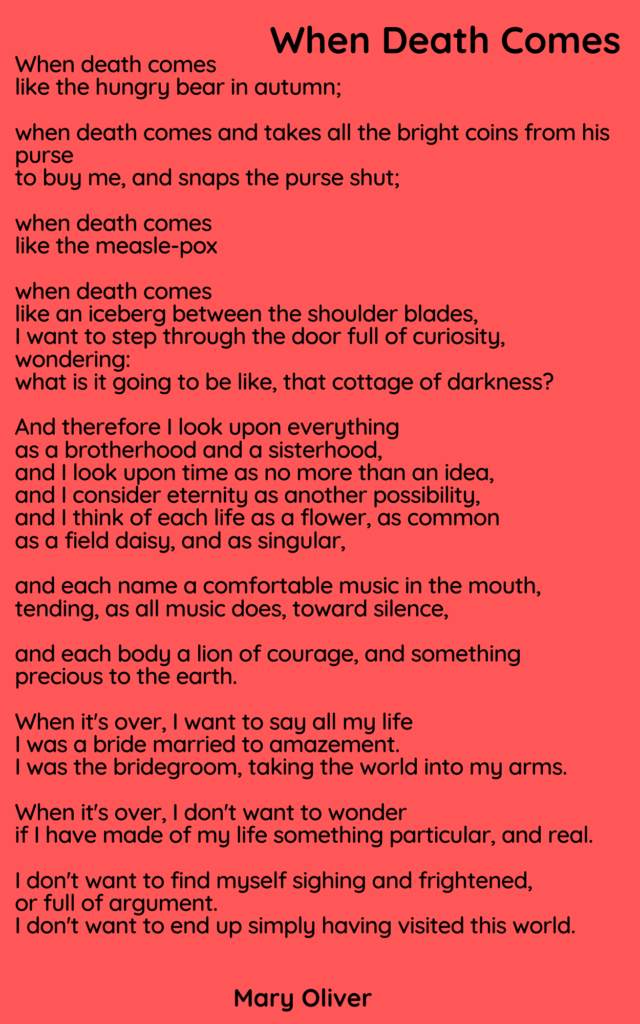

Each time I ask this question, I have varying responses. Today, my response is the Mary Oliver poem, “When Death Comes,” even with its unfortunate binary language:

So be it. See to it. Amen.