It is said that in each of his pockets, Rabbi Simcha Bunim carried a slip of paper. On one was written: f

or my sake the world was created...

How awesome is that?!?

On the other was written:

I am but dust and ashes...

How awful is that?!?

Both messages he carried with him, living his life in between these two realities.

What is it to live a life as if awestruck? Aware of the motion, and commotion, careening and gliding between these two experiences of the world – of the universe – overwhelmed, fearful, humbled, reverent, inspired? What is it to live a life understanding that these two experiences are not polar opposites – awesome and awful – but at their deepest root, are knit of the same stuff, two sides of the same coin?

Are the meticulous making of the awesome sand mandala…and the awful – or was that awesome too? – destruction of it?

It turns out there are many entrances into awe: song, prayer, dance, theology, philosophy, great art, great architecture, even great science. And possibly, death. Let me tell you a story of the most awful, and the most awe-filled, moment of my recent life.

Three weeks ago, the wife of a dear friend – and herself a dear friend – died. A year of awful for them both, in and out of long hospitalizations. Awful for my friend, now a widow. Awful for this woman, who had struggled for months with swallowing, not able to eat enough on her own. I had been visiting three weeks before, when her ambivalence about fighting for her life was palpable presence in the room; yet she was worried about disappointing others if she “gave up.” That was awful.

Then, I was there for the awe-filled part. Awe-filled: the minutes and hours after she died, I was there along with her dedicated, desperately sad friends, many of whom had known her for forty-plus years. I was with my friend, her wife of just under a year ~ for they had gotten married in the hospital when the cancer abruptly raged, (they had been together for the sixteen years before that). She was both in shock and completely present to her beloved.

Altogether, filled with awe at the absence of our dead friend and the presence of her dead body, we washed that body, we took cotton balls and tenderly anointed it with baby oil, and then put on clothing picked out especially. In twos, and threes, and just her wife alone, we said our good-byes. Then came the hospice nurse, to pronounce her dead. Then came the funeral home to take the body away, placed on a stretcher, covered. All of us put on our jackets and shoes. We created a human arch through which the funeral home personnel processed as they carried out the stretcher. We whispered and sang and said our good-byes.

As I said, a most awful, and a most awe-filled, moment.

Wherever or however you access it, Rabbi Lawrence Kushner suggests that when we enter into awe, it is the “Unio Mystica,” or being at One with the Holy One or the Holy One(ness). He writes,

There are many ways we reach for the Holy One(ness). We can attain self-transcendence through our mind in study, through our heart in prayer, or with our hands in sacred deed. We say, in effect, that through becoming God’s agent, though voluntarily setting God’s will above our own, we literally lose our selves and become One with the One whom we serve. It rarely lasts for more than a moment.[i]

According to him, it’s not about becoming the same as the Divine; it’s about forgetting the boundaries of the Self. Forgetting where you end and creation or existence begins. It is perceiving deeply, sensing in all the ways possible that creation is in you and you are everywhere in it.

Kushner practices from a Kabbalah perspective – an ancient, mysticial Jewish tradition – but these thoughts belong not just to Judaism. Think of Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh’s concept of Interbeing, and we are in the same place.

So, there are many entrances. Often, we think that to access awe, we must place ourselves in the midst of the rare and the extraordinary. Visit the Grand Canyon, or Machu Pichu, or Alaska before it melts. What if awe was available to us at home, in the ordinary?

There is an old story — told by many, I read it in Kushner’s book called Eyes Remade for Wonder — of a rabbi named Isaac, who lived in Krakow. He was a good man and he was poor. So, when he had the same dream, three nights in a row, of treasure buried under a bridge in Prague, he paid attention. He made the long journey only to discover that the king’s soldiers patrolled the bridge. He kept watch for several days and nights, hoping for his chance. Instead, the captain of the guard spied him. He was caught and questioned about his purpose there at the bridge. Rabbi Isaac told the captain about his dreams.

The captain laughed in his face! “You mean to tell me you believe in such things? If I believed as you did, I would be on my way to Krakow to find some rabbi named Isaac, because I have dreamed there is great treasure buried beneath his bed!” The captain never asked our friend Isaac his name or his vocation, but did allow him to return home, which he did. Upon his arrival, he pushed aside his bed, removed the floor boards, and dug up the treasure that had been there all along.[ii]

That story makes me wonder what possibilities for awe am I missing here, where I make my home? Here, among the mundane? On this side of the fence, even if the grass is not greener?

What about you? What might you be missing that is right under your nose?

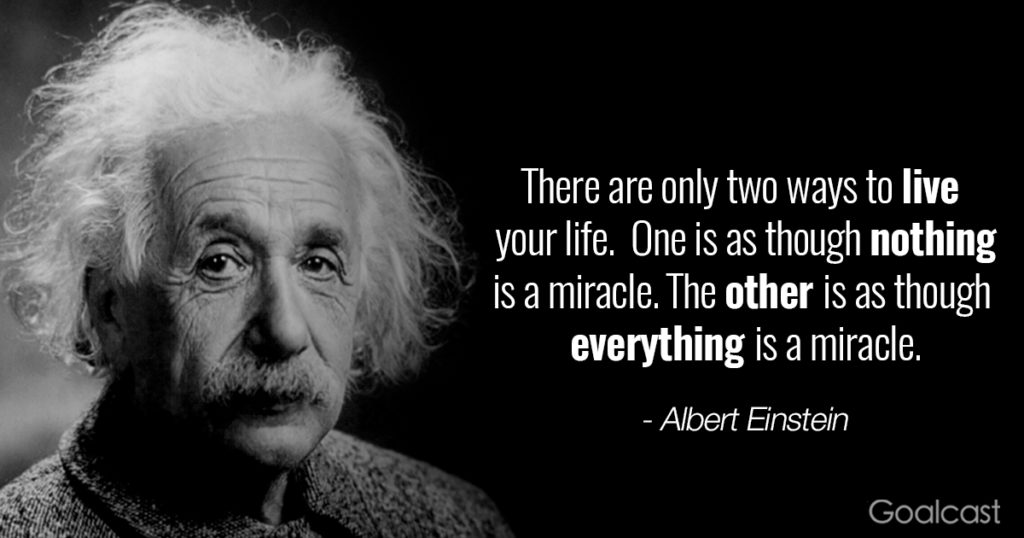

Like the treasure beneath Isaac’s bed, might there be entrances into the Holy, to the Awe-filled, the Awe-some, nearby, waiting for you to discover them? Supposedly Albert Einstein said,

This might be another version of Rabbi Bunim’s two pockets. I know that while I’d like perceive the shine of miracles, I am often stuck in the tarnish of no miracles. So, while there is access all around us at all times to awe does not mean that we actually open that door.

There’s a wonderful Jewish tradition called midrash: telling stories to fill in the gaps from ancient scripture. Likely you are familiar with the broad strokes of the miracle story of the parting of the Red Sea, right? When Moses, with the aid of god, led the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt by crossing parting the great waters? Well, there’s a midrash that focuses on two of the people who made that journey.

In the midrash, they are given names: Reuven and Shimon. Like all the others, they cross the bottom of the sea, yet they complain the whole way. Though safe, the ground was muddy:

Reuven stepped onto it and curled his lip. “What is this muck?”

Shimon scowled, “There’s mud all over the place!”

“This is just like the slime pits of Egypt!” replied Reuven.

“What’s the difference?” complained Shimon. “Mud here, mud there; it’s all the same.”

And so it went for the two of them, grumbling all the way across the botom of the sea. And, because they never once looked up, they never understood why on the distant shore everyone else was singing songs of praise. For Reuven and Shimon, the miracle never happened.[iii]

This story, too, makes me wonder: have there been miracles – opportunities for awe – that I have missed, due to my own sense of grievance, or my own ignorance, or distraction, bidden or unbidden? Due to my focusing on the solid facts beneath my feet, instead of the intangible possibilities swirling around me?

How about you? Have you chosen to see the awful, when the awesome was available?

The skeptical mind, the mind habituated to poo-pooing miracle-talk, the mind that would rather explain why starlings fly as a collective awe-inspiring pack called a murmuration than let the awe-filled elegance wash over and be enough, calls out and asks, what’s so important about awe? And chides, don’t make me give up my science and my reason. And by god, don’t make me have to do god, if you want me to even consider your invitation.

If that is you, I offer two gifts. First, the work and words of Phil Zuckerman, author of Living the Secular Life, in which he writes about “awe-ism:”

Aweism is the belief that existence is ultimately a beautiful mystery, that being alive is a wellspring of wonder, and that the deepest questions of life, death, time, and space are so powerful as to inspire deep feelings of joy, poignancy, and sublime awe. To be an aweist is to be an atheist and/or an agnostic and/or a secular humanist-and then some. An aweist is someone who admits that existing is wonderfully mysterious and that life is a profound experience. To be an aweist is-in the words of Paul Kurtz-to embrace and experience “joyful exuberance” sans theistic assumptions. Aweists suspect that no one will ever know why we are here or how the universe came into being, and this renders us weak in the knees while simultaneously spurring us on to dance.

So that’s awe from a secular point of view. Here’s awe from a scientific perspective.

Dr. Melanie Rudd, from Stanford University, studies the phenomenon of awe[iv]. She says awe has two defining characteristics. One is the sense of perceptual vastness or immensity – this might be size (think Grand Canyon) but it can also be scope, or power, or complexity (think of those sand mandalas we saw earlier).

The second trait is what she calls “the need for accommodation.” For something to evoke a sense of awe in us, it must challenge our mental structures or worldview. We must work to accommodate what we are perceiving. That need for accommodation is the likely source when we experience the fearful or humbling aspects of awe: we are confronted with something outside our ability to fully understand, brought into the territory of uncertainty. Not comforting, and, at times, awful.

Research shows awe is beneficial. This past May, a study came out that suggests that awe helps us to stop ruminating on our problems and daily stressors, inspiring generosity and a sense of connection with others.[v]

Dr. Rudd’s research shows that awe increases humility. It results in our feeling smaller and – this is key – AND connected to the larger world, the larger universe. Not small and alone, but small and connected.

Secondly, in Dr. Rudd’s studies, and this is relevant, given our service a few weeks back about slowing down since we haven’t much time: experiencing awe impacts and expands our perception of time. We feel that more time is available.

Lastly, connected to that shift in the perception of time, we feel more open to the prospect of learning, which somehow draws us to create. Which kind of leads us full circle back to that list of human responses to awe, the many entrances into Unio Mystica: song, prayer, dance, theology, philosophy, great art, great architecture, even great science.

Kinda cool, huh?

~~~

I want to close another loop – one related to my friend whose wife died. She texted me while I was writing this sermon. When I told her that I was struggling with writing my sermon on awe, she offered her take on it. With her consent, I share what she wrote. Listen for some of Dr. Rudd’s concepts — the unknowing and uncertainty that leads to the need for accommodation, the immensity of the experience that there is a gap that must be bridged…

Well, for starters, you bridged the gap between awful and awesome on that Sunday night to Monday when you showed up for me! I had no idea I needed you and how important you became in that space between an in the beginning and the end. Maybe you didn’t know either? Birth and death (metaphoric and actual) are awful and awesome. In between we hopefully keep showing up because and in case our people are in need of hand holding, witnesses. Or in the words of Hafiz, in the poem called A Great Need:

Out

Of a great need

We are all holding hands

And climbing.

Not loving is a letting go.

Listen,

The terrain around here

Is

Far too

Dangerous

For

That.

~~~

As our reading from the Poet Laureate of the United States implores us to do, let us remember that you are this universe and this universe is you.

As our Unitarian ancestor says at the top of your order of service, “Let us express our astonishment before we are swallowed up by the jaws of the abyss.”

Let us not forget to look for awesome possibilities and hidden treasures that hide in our midst, available to us only if we embrace our dreams.

As we make our way through the mud and muck of our lives, may we not forget to look up and around, to perceive the ordinary miracles around us, reminding us of the blessings in our lives, the grace extended to us even in the midst of our fear, and the possibility of liberation for all, even if we cannot in that moment feel it.

Let us live our lives careening ever so gently between the realities in the rabbi’s two pockets, for we live there, whether we want to or not.

Amen. Blessed be.