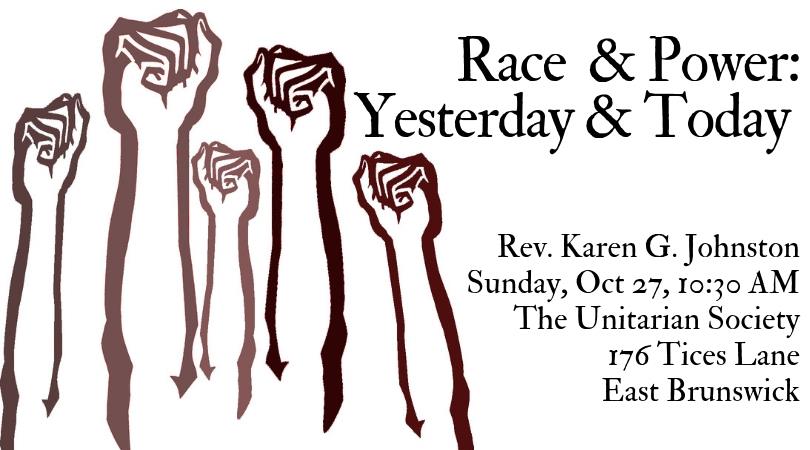

The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick, NJ

October 27, 2019

Fisticuffs.[i] Violent shoving. Spitting in the face. Name calling.

In June, I preached on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, what is commonly understood as the start of the gay or queer liberation movement. But the aggressive behavior I just described, while it did happen in June of 1969, was not in front of the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village. It took place at General Assembly – yes, our General Assembly, the annual gathering of Unitarian Universalists across the country and the globe – in Boston.

1969 was quite the year.

As I said last week, “Our whole existence as Unitarians, or Universalists, or Unitarian Universalists, we have been engaged in controversies related to race and power.” Today we are going to explore what happened a half century ago and how echoes, some subtle, some incredibly loud, are reverberating today.

Before I go further, I want to affirm that Unitarian Universalism is, and always has been, a multi-racial, multi-cultural movement. There are people of many races and ethnicities who are Unitarian Universalists, including who are members of this congregation. Yet, we cannot hide from the reality that we are predominantly white, not only in membership and attendance, but also in cultural comforts and leadership. We have aspirations to be more multi-cultural than we are. We have a gap that we cannot easily explain. It causes pain, and sometimes harm, to the people of color who are us. So, while I tell a story today that is largely Black and white, I want to explicitly recognize, that it is not our only race story.

In 1966, Reverend Steven Frichtman, a white minister at First U in Los Angeles, preached these words upon observing the emergence of Black Power on the civil rights landscape:

“The future will be hard, stormy, and unpredictable. Our own hearts will often have to change, our subconscious minds must be cleansed. Our own value system must be shaken up. And we must not run away from it because we grow weary in the struggle.”

The United States was responding in one way or another with the emergence of Black Power, whether they knew it or not. Black people were demanding that they get their fair share, that Black is Beautiful. It raised defensiveness and fear for those who were not ready, who felt threatened, or who felt that too much was being asked too quickly. The parallel with our own time, and the emergence of the Black Lives Matters movement, is undeniable.

Until a decade or so ago, this era had been known as the Black Empowerment Controversy. You heard what Reverend Sinkford suggests it be called more accurately: the White Power Controversy. It has a certain ring of authenticity to it. In the end, I think what has most stuck is the politic “Empowerment Controversy.” Even without the nomenclature, race still vibrates throughout this part of our history.

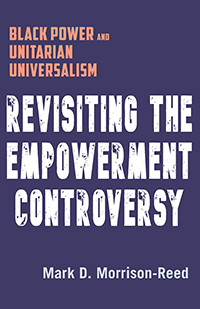

In summarizing this history my primary, but not only, source was, Revisiting the Empowerment Controversy: Black Power and Unitarian Universalism, written by Reverend Mark Morrison-Reed. Here is an incomplete timeline:

- UUs proudly take part in the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, including two who would become civil rights martyrs in 1963: Reverend James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo, both white. We also have congregations that attempt to use our polity to assert their right to stay segregationist.

- Black Power arrives on the scene, nationally and within Unitarian Universalism.

- In October, 1967, the UUA holds a conference to develop a response to Black Power. Out of this emerges the Black Affairs Council. Unexpected by the white male leaders of the UUA, BAC insists in choosing its own leaders and articulates a philosophy much in line with Black Power.

- A group with an integrationist philosophy, called Black and White Action, alos forms. From the beginning, the philosophy of these two groups are in conflict, and competition.

- In the spring of 1968 there are riots across the nation after the assassination of Dr. King – a man who told us that “a riot is the language of the unheard.”

- BAC demanded that the UUA fund them for $250,000 a year for four years – a million dollars that in our time would be like $7 million. BAC would have complete control over the money.

- At General Assembly that year, a vote overwhelmingly approved the formal establishment of BAC and full funding.

- The 1969 General Assembly was in Boston. The division between BAC and BAWA had grown deeper. BAC council members walked out of General Assembly. Rev. Jack Mendelsohn, a white minister, called for others to join them in solidarity. Four hundred white people joined the walk out (about one fifth of the voting delegates). This was when one of Jack’s colleagues spit in his face.

- Delegates voted to continue the funding for BAC, but not for BAWA. The vote was very close, nearly 50/50. This did not bode well and marks the beginning of the end.

- After GA, the new UUA president discovered that the Association was nearly bankrupt. This had not been made public. Looking to the survival of the Association, President Robert West cut funding in many areas, including to BAC.

- This was not received well by members of BAC or their allies. It was seen as yet another betrayal by white leaders and a faith movement that continually placed African Americans’ needs last. BAC disaffiliated from the UUA.

- At General Assembly in 1970, delegates ended all funding to BAC. BAC eventually disbanded.

- A significant number of Black Unitarian Universalists, as well as white ones, to left Unitarian Universalism[ii]. Most did not return.

In the fifty years since, there have been numerous reflections from different perspectives on what happened and why. Mark Morrison-Reed has written extensively on this topic. He notes that the passage of time was necessary to allow what had become metal hot had to cool for it to take shape that we might be able to recognize and make use of. Morrison-Reed’s conclusion in his latest book, which came in 2018, surprised me. Here are his words:

Theorizing about the role that paternalism and patriarchy played during this era is a more speculative endeavor than chronicling what happened, but the effort leads to the most cogent explanation for why the empowerment tragedy played out as it did. Patriarchy turns to violence to depose the leader when it must, because patriarchy is about the exercise of power. In this case, it was also transracial and manifested in both the generational conflict within the UUA and in BAC/BUUC’s overthrow of the African American old guard.

Morrison-Reed, an African American man, concludes that it was racialized patriarchical power grabs at the heart of the division and rupture. While we lost a higher percentage of Black UUs, we lost members of both races. Both BAC and BAWA had Black and white supporters. Morrison-Reed drilled down deeply in this book, so it’s a compelling supposition.

While Morrison-Reed names patriarchy as the culprit, this does not let white people off the hook or mean that racism did not play a critical role. It was a complex and deeply destructive combination of race and gender oppression that wreaked havoc, not one or the other. A havoc that brought lasting loss to our faith movement, loss of cherished members from congregations, and even the splitting of lifelong friendships and marriages.

~~~

There are cycles in our faith movement’s engagement with race, racism, and white supremacy culture. After the controversies of the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a decade or so where we did all kinds of social justice work, as long as it was not explicitly racial justice work. Some might call it avoidance. Some might call it healing. Probably it was a bit of both.

Echoes of the Empowerment Controversy remain with us today. An awareness of the origins of these echoes helps us to build the Beloved Community to which we aspire and about which we dream.

Paula Cole Jones, who works for the UUA and has a decade and a half of experience working with congregations, observed over and over that a person can believe they are a “good UU’ without ever thinking about or dealing with racism or other oppressions at a systems level. This struck her, a Black woman, as wrong. She led the process of creating an 8th Principle to correct this. Together with Bruce Pollack Johnson, a white member of a UU congregation in Philadelphia, they drafted in 2013 what is now known as the 8th Principle, which has been adopted by about a dozen UU congregations and has been recommended to the wider Association for adoption. It reads

“We, the member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association, covenant to affirm and promote: journeying toward spiritual wholeness by working to build a diverse multicultural Beloved Community by our actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions.”

In 2017, we saw the emergence of Black Lives of UU (BLUU), a Black-led UU organization that is in covenant with the UUA, helping to create Black leadership and healthy spaces for anyone from the Africa diaspora, as well as supporting other people of color, to find and make their place within Unitarian Universalism, instead of having to leave, instead of having to endure frequent microaggressions that come from well-intended typically white ignorance. Because that is a thing that we UU congregations do fairly well, I’m sad to confirm.

In 2018, the UUA promised BLUU to raise $5.3 million to fund their work, including committing a sizeable portion of its endowment, and inviting other UU organizations, including congregations, to commit as well. Along with nearly 700 other UU congregations, our congregation took part in the Promise and the Practice. We met the goal of contributing $10 per member to BLUU. Many people, myself included, feel that this our way of making good on a fifty-year-old promise by paying a long-standing debt.

We know that we are not done with race, racism, or white supremacy culture – out there or here, in our midst. America is not post-racial and neither are we. As it has always been, it still seems that General Assembly acts as a thermometer for showing us how hot the issue of race is in any particular year.[iii] This past year’s General Assembly was no exception.

In 2017, the Commission on Institutional Change was established to get to the root to what ails us racially. You heard an excerpt of their most recent report as one of our readings this morning. At this past year’s GA, the Commission conducted a survey. About one quarter of GA registrants responded. 60% ranked as 10 (the highest score) that the most important work for the future of our faith is anti-racism, anti-oppression, and multi-cultural work. An additional 30% ranked it with an 8 or 9.[iv]

On the other hand, the efforts to make space for voices of those with marginalized identities encountered the harshest backlash to date at this General Assembly, the wake of which continues to cause damage.

Last month, the Commission on Institutional Change reflected on General Assembly, asking some truly compelling questions that fit well with our theme of belonging this month. The Commission asks, “Can we recognize that there are legitimate and differing interpretation of our past and present? Can we reconcile our differences in love?”[v]

Whether we apply these questions within Unitarian Universalism, or to the transformations taking place in our larger culture, we must wrestle with what it is to be a predominantly white community in a society that is increasingly “browning,” — something that I personally welcome, but recognize causes me to have to learn new ways of being, to face uncomfortable truths, and to let go of certain expectations I was taught to have because of my white racial identity.

I think this is harder for those of us who have sat more solidly in traditional positions of power. I am thinking here of straight white males of Baby Boom generation — some of whom sit in this very room, and for whom I have genuine affection; one of whom I share a home and a life with.

The backlash that our nation experienced in response to the civil rights movement, in response to Black Power, has not gone away. In fact, in recent years, it has intensified. In addition to backlash from more conservative quarters, there is also unmanaged fragilities, both mild and extreme kinds, from all directions: conservative, center, liberal, and progressive.

We are not immune, though we like to hold ourselves apart from it. Indeed, we are in the midst of it. If we do not engage in thoughtful, intentional self-examination, it may very well, if we allow it, pull us apart.

Let us join with Reverend Sinkford, who says at the top of your order of service, that most days, he believes there is growing traction to point us toward hope.

Let us live into our aspirations of a deep and true belonging for all who are on the journey to Beloved Community.

Let us find ways to recognize legitimate and differing interpretations of our past and of our present. And may we work for a future together.

Let us find ways to reconcile in love.

Let us not grow weary in the struggle.

Amen. Blessed be.

[i] Morrison-Reed, Mark. Revisiting the Empowerment Controversy

[ii] Takahashi-Morris, Roush, & Spencer. The Arc of the Universe is Long, p. 11

[iii] Arc, p. 446

[iv] UUWorld https://www.uuworld.org/articles/coic-survey-preview

[v] https://www.uua.org/uuagovernance/committees/commission-institutional-change/blog/deepening-spiritually-reflecting