The Unitarian Society

East Brunswick, NJ

February 4, 2018

It is essential to read between the lines. I had already learned this, but when I was in seminary, I had the chance to learn it again. For instance, in Christian scripture, when Paul writes that women should be silent, he is doing so because women are Not. Being. Silent. If we were, there would have been no need for Paul to tell the Corinthians to hush us up.

It is essential to read between the lines. I had already learned this, but when I was in seminary, I had the chance to learn it again. For instance, in Christian scripture, when Paul writes that women should be silent, he is doing so because women are Not. Being. Silent. If we were, there would have been no need for Paul to tell the Corinthians to hush us up.

Reading between the lines gives us a richer understanding of the true texture of our own history. For instance, in her book, The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander mentions that during the era of so-called “Southern Redemption,” authorities outlawed the game of chess…between Black and white people.

What does this tell us? That instead of a natural, god-given racial divide, African Americans and whites were socializing, were friendly: were playing chess together –– else there be no need to make a law against it. The powers that be longed for a wide and hostile division, constructed it through criminalizing such contact, then penalized only the Black folk.

And why is this relevant for Unitarian Universalists?

Reading between the lines allows us to see that our roots are in unexpected ground. Reading between the lines, particularly thanks to the Unitarian Universalist minister and historian, Susan Ritchie, has allowed us to trace back some of our Unitarian history – the founding happenings in what was Hungary then, what is now the Transylvanian region of Romania — to a relationship with the Ottoman Empire and with 16th century Islam.

Yes, you heard me right: Islam. Is your mind blown? Good.

We know this, not because it had been stated forthrightly. In fact, there is evidence of erasure. We know this because it can be read between the lines in anti-Islamic and anti-Unitarian tracts of the time. These treatises suggested, with nefarious intent, that the newly emerging Unitarian church was an agent of Mohammed, this being a quick way to sabotage its leaders as illegitimate.

I wonder, friends, do you hear the echoes of modern day Islamophobia there? I do.

I want us to spend most of our morning in the 16th century but I also want to make sure that all of us in the room are working with the same basic information about our modern history before we go several centuries back.

Unitarian Universalism comes out of the merger, in 1961, of two separate Christian denominations: the Unitarians and the Universalists. While both were considered heretical in their own way, they were still fully within the Christian fold; thus, our primary history is rooted firmly in Christianity.

Unitarian Universalism comes out of the merger, in 1961, of two separate Christian denominations: the Unitarians and the Universalists. While both were considered heretical in their own way, they were still fully within the Christian fold; thus, our primary history is rooted firmly in Christianity.

Today, however, Unitarian Universalism no longer understands itself to be a Christian denomination (even as we honor and love individual UU Christians and practices among us). We do understand ourselves to be a religion of our own, and are recognized as such. While we value interfaith engagement and have amongst us many interfaith families, we, ourselves, are not an “interfaith religion,” though you sometimes hear people say that.

We are Unitarian Universalism: that plain and simple, that complex.

~~~

Back in the time of what was the Protestant Reformation – and remember, just this past October, 2017, we marked the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther hammering his 95 theses that sparked that revolution — our Unitarian and Universalist traditions were unsatisfied with these reforms, pressed for further adaptation beyond what would become mainstream Protestantism, and found ourselves more closely aligned with radical reformers of the time.

This year – 2018 — marks the 450th anniversary of one of our most cherished founding documents: the 1568 Edict of Torda. You heard it as our reading today. I’m going to read it again, in all its old language glory, noting that it uses the word, “diet” which means “assembly” and, of course, male pronouns where we moderns would choose otherwise:

His majesty, our Lord, in what manner he – together with his realm – legislated in the matter of religion at the previous Diets, in the same matter now, in this Diet, reaffirms that in every place the preachers shall preach and explain the Gospel each according to his understanding of it, and if the congregation like it, well. If not, no one shall compel them for their souls would not be satisfied, but they shall be permitted to keep a preacher whose teaching they approve.

Therefore none of the superintendents or others shall abuse the preachers, no one shall be reviled for his religion by anyone, according to the previous statutes, and it is not permitted that anyone should threaten anyone else by imprisonment or by removal from his post for his teaching. For faith is the gift of God and this comes from hearing, which hearing is by the word of God.

In this, I wonder if you can hear the echo of our own freedom of the pulpit and the pew – your minister gets to preach what she deems necessary and lay folk – you pew-sitters, you — are free to believe what you deem right and necessary.

This is good stuff. Particularly when you consider the wider political context: all around Europe there was a lot of killing for believing something other than what whatever leader where you lived believed or decreed should be believed. Catholics being killed for not being Protestant; Protestants being killed for not being Catholic. And outside of this part of Hungary, if you were Unitarian, you got killed for being neither.

And by good stuff, I do not perfect stuff. For instance, the tolerance extended only just so far: to the Catholics, the Lutherans, the Calvinists, and the Unitarians. Well, hey, it was the first time that we made the “marquee of religious tolerance.” We made it onto the marquee because of those four, in that small corner of the world, we were largest in number.

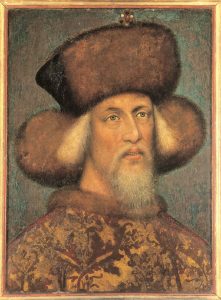

We made it on the “religious tolerance marquee” because the Edict of Torda was put forward by our one and our only Unitarian king, John Sigismund; was written by our Unitarian martyr, his court preacher, Francis Dávid; as well as by the king’s doctor, also a Unitarian, Giorgio Biandratta; and influenced by the king’s humanist mother, Queen Isabella.

(Also this good stuff wasn’t perfect stuff for another reason: it didn’t last. Because after that one and only Unitarian King died and the next one came, Francis Dávid, the one who wrote the Edict, was imprisoned for “innovation in religion,” one of the very things the Edict was protecting against. He died in a dungeon prison.)

~~

Here’s the thing that blew my mind when I first heard about it. Here’s the thing about our roots being in unexpected ground. We also made it onto the “religious tolerance marquee” (and I swear that is the last time I will say that phrase) because the Sultan Suleyman of the Ottoman Empire, years earlier, came to the rescue of Queen Isabella, and her then-infant son, already-named-king, Sigismund, who were under attack by the Hapsburgs.

If this benevolent Muslim emperor had not created what Ritchie called “one of the safest places in Europe for the development of progressive Protestantism,” we Unitarians would not be on…well, no one would have seen our name in the lights of this new religious freedom. Without the protection of the Muslim-ruled Ottoman Empire, we would not have the lineage we have today and we would not be celebrating 450 years of an awesome declaration of religious freedom.

Blew my mind. Is it blowing yours, too?

It turns out, even though the Edict of Torda is often referenced as the first of its kind, that isn’t quite true. It’s been believed to be true until not all that long ago, mostly because of enacted impulse to erase all evidence of a liberal Islam that was part of that corner of the world, a liberal Islam that supported religious tolerance, and, in fact, provided the groundwork for the Edict of Torda we celebrate today.

It turns out that even before there was a Francis Dávid or a Unitarian King John Sigismund or even a Sultan Suleyman, there was a Pasha of Buda. Not Buddha, like Buddhism. But Buda, like the city of Budapest.

This Pasha – a Muslim official – twenty years before our beloved edict, in 1548, when asked by Catholic authorities in Tolna to kill a pastor for his unapologetic reformed ideas, refused the request. He refused and took it one step further, issuing an edict of toleration which stated, in part, that

“preachers of the faith invented by Luther should be allowed to preach the Gospel everywhere to everybody, whoever wants to hear, freely and without fear, and that all Hungarians and Slavs (who indeed wish to do so) should be able to listen to and receive the word of God without any danger.”

Do you hear the echo? The one about listening to and receiving, hearing the word of god? Do you hear the freedom of the pulpit and the pew? Ritchie tells us that there is no paper trail that links the Pasha’s edict and the one written by our Francis Dávid. However, she makes a compelling argument that if Dávid did not know the Pasha personally, he had to have been well aware of the Pasha, given his role as a church administrator who abided by the Pasha’s governance.

Do you hear the echo? The one about listening to and receiving, hearing the word of god? Do you hear the freedom of the pulpit and the pew? Ritchie tells us that there is no paper trail that links the Pasha’s edict and the one written by our Francis Dávid. However, she makes a compelling argument that if Dávid did not know the Pasha personally, he had to have been well aware of the Pasha, given his role as a church administrator who abided by the Pasha’s governance.

In general, Ritchie believes that rather than a cause-effect relationship between Islam and Unitarianism, she paints “a portrait of two cultures more greatly enmeshed in patterns of creative engagement, mutual attraction, and circular patterns of influence than we have imagined before” (p.15). In fact, she asks – and this is particularly provocative given modern depictions in mainstream media in America and Europe –

“Could it be that toleration, that most precious inheritance of the European Enlightenment, was instead a shared liberal Christian/Muslim undertaking?” (p.15)

~~~

Why all this history in today’s sermon? Because history is not just the story of yesterday, but often is the story of today and quite possibly tomorrow.

Have you ever noticed – in news reports and political speeches? in movies and novels? perhaps in your own mind? — the stereotype of the oppressed Muslim woman, forced to wear clothing against her will, living at the beck and call of Muslim men who restrict her and disrespect her? What if I were to tell you that there is evidence that our modern-day stereotypes are rooted in anti-Islamic propaganda contemporary to the time of the Edict of Torda? Are rooted in attempts to undermine the multi-faith, religiously tolerant societies that our religious ancestors were trying to cultivate?

There were accounts, the purpose of which was to “enflame ethnic hatred against Turks.” (Ritchie) Some were constructed with liberal Protestants in mind, particularly those living under oppressive conditions in the Hapsburg lands proximate to Hungary who might, given how hard their lives were under Catholic rule, be tempted to see the Ottomans in a friendly light.

If the line between the Pasha of Buda’s edict and the Unitarian Edict of Torda was not direct, this connection nearly is. It turns out that there is a genre of contemporary European literature that characterized Muslim women as gender oppressed and that this caricature – this stereotype – was constructed intentionally to offend liberal Christians who might have otherwise appreciated Islam or found within it beneficial aspects.

Now granted, patriarchy is everywhere, so I’m not saying that there’s not a culture of misogyny in Muslim-majority countries. I’m just saying, it’s not only there. We do a fair amount of scapegoating of Islam for a practice that exists in every religion, every nation, every culture.

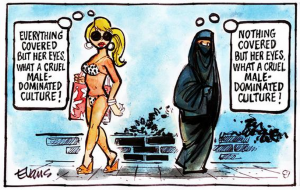

My favorite modern response to this particular dynamic of scapegoating Islam for sexism is a political cartoon by Malcolm Evans.

A Western woman, wearing a bikini, high heels, and sunglasses, walks past a Muslim woman wearing a burka — all we can see is her eyes. The thought bubble in the Western woman is one we are familiar with, and perhaps even know in our own hearts, “Everything covered BUT her eyes! Cruel male-dominated culture!” The thought bubble in the Muslim woman goes like this: “NOTHING covered but her eyes: what a cruel male-dominated culture!”

I raise all this for your consideration for two reasons. Reason one: to lift up that some of the seeds for current-day Islamophobia, including the kind that finds its way into liberal and progressive hearts, were sown at the time our ancient people were trying to build within hearts and minds and society a way for religious tolerance; that these seeds were sown to subvert our religious ancestors and the world they dreamed about.

Those nefarious anti-Islamic and anti-Unitarian seed sowers, they were not wholly successful. Hallelujah!

But they were not unsuccessful, either. Which leads us to reason two: this was not just their work back then. It is our work now.

With the rise in Islamophobic actions and crimes; with our very government targeting Muslim communities with travel bans and restrictions on immigration, this is very much our work to do now. Ours as Unitarian Universalists and ours as residents living in Central Jersey, where one of our greatest natural resources is the ethnic and religious diversity that the 21st century has gifted us in our neighbors, our co-workers, tradespeople we encounter every day, elected officials who serve our communities, friendships that expand our worlds.

Let us honor our roots in this unexpected ground.

Let us defy the stereotypes handed to us, sometimes handmade for our own sensibilities, and seek larger possibilities of a shared world.

Let us amplify the presence of liberal Islam in the past and in the present, including among devoted Unitarian Universalists who understand themselves as sharing identities in both spiritual worlds.

Let us be more than a little bit subversive, building friendships and partnerships across divides that others attempt to coarsen – across differences of religion, of nationality.

Francis Dávid, our early Unitarian ancestor, famously said, “God is One.” To end this sermon, let us raise up our voices singing the hymn, “We Would Be One,” bringing melody from deep within our hearts, voicing these words: “We would be one in living for each other to show to all a new community.”

Amen. And may it be so.