September 17, 2017

The Unitarian Society, East Brunswick

(this sermon was delivered extemporaneously, though written in full ahead of time; the content is substantially the same, though minor changes exist between this text and the one preached)

Place is important. Where we are informs who we are and who we become. When we are rooted in our place, we can expand our wings and feel our fullest power. It’s part of why I am excited for our children today – their One Room Schoolhouse is outside on the grounds, connecting them to this place in a way that being inside the building cannot do, connecting them with our Seventh Principle in ways that only Nature can help make real.

To grow my roots here, in this place of all places, one focus of my study leave this past summer was getting to know New Jersey better. Of course, everyone has an opinion about how to do that. Read Junot Diaz or Phillip Roth. Go to Patterson. Watch the Sopranos (which I did not do, have never done, and don’t plan on doing – that’s not the New Jersey I want to get to know).

I had my own ideas, as idiosyncratic as this may seem. For instance, I visited New Jersey’s only green burial preserve. I hope to tell you more about it at the end of October, but I just want to say that there is a line from a poem by Wendell Berry – it is at the top of your order of service: there are no unsacred places; only sacred places and desecrated places. This green burial preserve is a fine example of a sacred place, sustained as such in how they honor the land and honor the natural processes of decomposition.

I read Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography, which seems apt, given his iconic status as a Jersey boy. I also read two books about the theologies in the Boss’ music – one written by retired Unitarian Universalist minister Jeffrey B. Symynkywicz, and a more recent one, written by a Rutgers professor, Azzan Yadin-Israel.

Aside from my field trip to Steelmantown Cemetery, and reading more about icon Bruce Springsteen, my New Jersey study leave time led me to a heart-breaking piece of local history that I mean to share with you today.

But let me back up a bit. Back to a workshop presented by UU religious leaders of color in New Orleans this past June.

During the Q & A time, a white colleague asked what she can do to address racism since her congregation is not only majority white, but was 100% white. The response came from religious educator of color, Aisha Hauser, who has been an important voice in our faith movement for a long time, and who gained more visibility in this past half year as we have more actively struggled with patterns of racial bias and white supremacy in our own midst. Aisha said, “If you are anywhere on this continent and in a space that is white-only or white-majority, it wasn’t always that way. Start there. Start with that story. See where it takes you.”

It wasn’t always that way. Start there. Start with that story. See where it takes you.

Even though our congregation is by no stretch all white, this piece of advice stuck with me.

There is a story of this place, this here. Pieces of it have been made public in academic history journals and by local history efforts. When I learned this story about East Brunswick, I heard the echo of Aisha Hauser’s admonition – start with that story, see where it takes you — I knew that I had to share it with you.

This story speaks of a place desecrated by the forced removal to slavery of human beings, done so for profit, done so by abuse of judicial power. It is a story of white supremacy and it is a story of our place’s white supremacy. As such, it belonging to the same place we belong, it makes it our responsibility how we respond, it makes it our responsibility how to change a place that has been desecrated back into a sacred place.

New Jersey was the last of the Northern states to abolish slavery, voting in 1804 to do so in a gradual way – so gradual that there were still 16 slaves in this state when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1865. Until 1812, New Jersey law that allowed the removal of slaves and apprentices out of state (and into the Deep South) with their (or their mother’s) assent. This is important because six years later, Judge Jacob Van Wickle, who lived here in East Brunswick and served in the Middlesex Court of Common Pleas, used his corrupt court to falsely claim the consent of children and their mothers to being sent to Louisiana, promising them pay, promising them safe return to New Jersey, promising these things all falsely, and benefitting financially.

We heard some of their names when Marie read them earlier:

Harriet

Susan

Mary

Augustus,

Rosinah, aged 6 weeks

Dianah

Hercules

Dianah

Dorcas

It is my understanding that Van Wickle brought these people, either under false circumstances or against their will, into his court. In one case, in Rosinah’s case, he placed her in his courtroom, asked if she – a six week old — would like to go to Louisiana and when the infant cried, he announced to the court that cry was the cry of assent. Then, with that child’s mother next to her, Van Wickle basically said, “Your child is going to Louisiana. Where would you like to go?” In this devious way, Van Wickle stole the real or promised eventual freedom of those people, consigning them and their next generation, to a life of slavery. Despicable.

Van Wickle was able to do this with the help of at least two other primary co-conspirators, both of whom were related to him by blood or marriage. They all benefitted from this financially, as payment for slaves in Louisiana was high. However, they were not able to get away with this for long. Once this slave trading ring was made known, there was public outcry. There was the founding of the Middlesex County Association for the Prevention of Kidnapping – and the eventual legislation to prohibit the “exportation of slaves or servants of color” which shut down the slave trading ring within six months of its inception. Van Wickle’s co-conspirators were eventually indicted. Van Wickle never was, though it was his home that was used as headquarters. He continued to serve as judge, and histories stopped paying attention to this dastardly deed. And in the way of things, particularly in the way of white supremacy, it was erased from our collective knowing. It was only in the 1990s, when this history was recovered, that we can now know it.

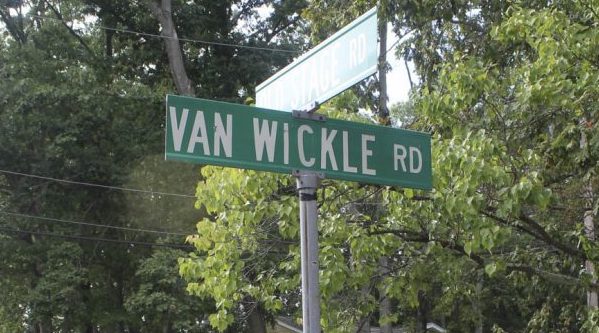

Just off Old Stage Road, here in East Brunswick, near the border with Spotswood, there is Van Wickle Road. The people in the 1970s or 1980s who named that street did not know this history, did not know that Judge Van Wickle had done such a devious thing. The tarnish on Van Wickle’s reputation had been polished by the whitewashing of history. No one knew at the time of the street naming, but now it is known.

More to the point: now we know. Now you know. What are we going to do with the information? How do we become faithful stewards of this history? Given that this is our place – it does not matter if you reside in East Brunswick or not, your congregation exists here, and thus our roots are here, a source of your authority and power is here, a place of your accountability is here – what are we called to do?

This has been my question ever since I learned this history this summer during my study leave. I did not go looking for this history, yet in the course of a conversation, I came to know this horrendous history. And I cannot unknow it.

The East Brunswick Township Council next meets on September 25. It is my intention to attend that meeting, to find the courage to speak during the public section, and to add my voice to those who have asked the Council to remember the deeds of this slave trader judge and to change the name of the street. I will ask them to do so before the end of 2018, the 200th anniversary of act wherein he sent those people – let me again say their names: Harriet, Susan, Mary, Augustus, Rosinah, Dianah, Dianah again, Dorcas, Hercules and others with names unknown to us — into permanent slavery.

We have a Racial Justice Team here at TUS. We met earlier this week to reflect on the question, “Given our Unitarian Universalist principles by which we seek to live, what is our obligation as a good citizen of this Township?” That team came up with some ideas and they are all invitations to you – to all of us:

- Read the brief summary of information in the order of service;

- When next Wednesday’s email comes out, read the information provided there – it will be more in-depth, including written materials and some video links;

- A link to today’s sermon will also be there;

- As an individual, consider signing a joint letter to the East Brunswick Township Council, asking them to change the name of Van Wickle Road. That letter will be available next Sunday for you to sign – so that it can be presented to the Township Council;

- Consider attending the Council meeting on Monday, September 25 at 8pm – any and all of you are invited, but especially if you are an EB resident. Personally, I welcome your company, even if you don’t speak. My confidence will be stronger if I have your good company. More importantly, the more of us who show up, the more powerful of a message it sends to the Council.

Last week, I drove the short length of Van Wickle Road. It’s lined with homes. I wondered about the folks who live there. I wondered how many know this history. I’m guessing not many. I wonder if there has been any attempt to inform them. I wonder, once they do know, what it will mean to them? There is something powerful about place and knowing its history, knowing one’s connection, and thus becoming the steward of that history.

But I wonder about those folks, for they are just like us, could be us – how many would be allies, seeking a name change despite the inconvenience? How many would be “apathetic”? (which is how one historian described New Jersey’s general attitude history when it came to the abolition of slavery). How many – god forbid – might resist a name change, claiming good intentions, but the impact being a dangerous message about who earns commemoration in this town and in this nation.

I am struck by the powerful convergence happening here. Our nation’s active grappling with Confederate monuments these past few years, but especially these past few months. The ugly uprising of white supremacists with torches in hand, no hoods to hide their faces in Charlottesville last month. And now history — how a corrupt East Brunswick judge sold away a hundred people into slavery and how he has a street named after him; how this happened 200 years ago next year – 1818 to 2018; how there was a public outcry then; how there can be a public outcry now.

As Unitarian Universalists, as people of conscience and people of faith, as people of this place, of this “beautiful neighborhood” as Nick sang earlier to our children, we can be a part of making once again sacred, a place and a history desecrated by human trafficking in African American slaves.

Let’s start here. Let’s start with this story. Let’s see where it takes us.

Amen.

** Deep gratitude to the extensive historical research conducted by Richard Walling on this subject and for his persistent advocacy to have this wrong made right.

Thank you Rev Karen. Not from your neighborhood but in our hearts.