I don’t remember ever needing or wanting a burial spot, though I do remember thinking about it from an early age.

When one looks at my family, there are many ways to respond to the dead human body and the human desire to mark one’s death by location. My father’s ashes were spread near and in a river that he had loved to fish as a young man. When my Great Aunt Ruth was buried in one of the Jewish cemeteries in Sharon, Massachusetts, I found it powerful to shovel dirt onto the casket. The plan for my mother is to have her ashes interred with the ashes of her mother and father, in the valley where generations of her family lived out their lives. My husband cares less about what ultimately happens to his dead body as that we try, in the first three days after his death, to have his spiritual community be able to do the proscribed rites and rituals required.

I did not grow up with religion and so, was not raised with dogmatic admonitions of what would be necessary at the end of my life, either ritually or salvifically. As a young adult, when I learned of the cost involved in a typical burial, cremation seemed to be the way to go. Then I learned about the excessive pollutants thrust into the air when human bodies burned. I knew that if I could avoid it, I would. Thus entered my interest in the green burial movement.

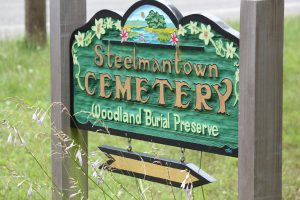

I recently visited Steelmantown Cemetery, the only green burial preserve in the state of New Jersey. What a beautiful and peaceful place.

There are black iron gate that marks the entrance. After walking a short distance into the space, it becomes clear that this is a special place. The shape of an old cemetery becomes evident. Then there is the reconstructed chapel, built originally in 1910, it was vandalized and burned in the1950s. It is si mple and sweet, with natural light through the windows or from lamp flame. It also holds an old pump organ. There is a small outdoor seating area with stone benches that suggest sitting there would be a good idea, just not for long periods of time.

mple and sweet, with natural light through the windows or from lamp flame. It also holds an old pump organ. There is a small outdoor seating area with stone benches that suggest sitting there would be a good idea, just not for long periods of time.

There is an outhouse (a two seater) in recognition that those of us still among the living still have bodily functions we must perform.

The cemetery is old. The oldest section dates back to the 18th century and contains people who died in the Revolutionary War. There are more recent – 19th through 20th century – traditional grave sites with cement or stone stones with names and dates, perhaps a word or two about the person.

There is the section that includes 138 markers for “boys” (really, these were men, some of them dying in their seventh decade) from a local home for the “retarded.” Each of these markers has a name, the year of death, and the age of the man at his death. I appreciate that each of these deaths is marked and named; where I last lived, there was a potter’s field where the graves were unmarked for the hundreds of dead from the local once-mental asylum.

And then there is the natural section, the section that is growing: the green burial preserve.

The cemetery’s mission is “to provide a place of sanctuary, open to all, and preserve its unique history and the pristine environment it encompasses.”

The cemetery has a long history, which I won’t go into here. Most recently, the Bixby family, with ties to the cemetery already in place (families members are buried there), decided to save it from neglect and disrepair. Then, struck by inspiration, they decided to turn it into a green burial preserve. For this, I am – and we all should be – deeply grateful to Ed Bixby Jr. and and Ed Bixby Sr. whose company I was blessed to have as I toured the cemetery.

Burial sites are in the midst of a forest, with a former cranberry bog nearby. The paths are covered in a carpet of moss. Graves are dug by human effort and shovel. It takes two people about six hours to dig. Given the forest setting, graves can be dug in all seasons. Bodies are brought from the iron gates at the entrance on a large-wheeled wagon, pulled by human effort. All this reminds us that none of this is a new innovation. It is, in fact, how it used to be done, for centuries. Most likely for millennia.

The gravesites that already contain a human body are the same general shape. Depending on how long ago the burial took place, there are varying degree of mounded-ness. More recent gravesites peak above the surrounding ground. Ones from five years ago or longer seem more level. This is the natural consequence of not having a cement vault that keeps hidden the effects of decomposition. Here, in this green burial preserve, we get to observe the natural processes otherwise hidden from view.

The gravesites that already contain a human body are the same general shape. Depending on how long ago the burial took place, there are varying degree of mounded-ness. More recent gravesites peak above the surrounding ground. Ones from five years ago or longer seem more level. This is the natural consequence of not having a cement vault that keeps hidden the effects of decomposition. Here, in this green burial preserve, we get to observe the natural processes otherwise hidden from view.

All gravesites are marked by a large stone. You can choose one from the collection, gathered over the years by Ed Sr. or you can bring in your own. Only natural markers are allowed. There are stone markers on sites that have been bought but not yet used. You can purchase sites side by side, or for whole families to be near each other.

There are stone markers on those sites that already have occupants. Some of the stones – more than not – are etched with words. Some are the name of the deceased, their birth and death dates, perhaps a message to or from them. Some stones are etched but do not have the name of the person, but a message related to their life.

My favorite marker not made of stone. It was made of wood. It topped a mounded grave site that showed the most active wear from earth settling. This seemed aptly-suited, given this person had chosen a marker, but one that would give way to the natural processes of decomposition, just like his body. He was a surveyor – had been, in fact, the surveyor for the cemetery, so I imagine that he had a deep affection for the land and its ways, and wanted to join it as fully as possible. No stone carved with human attempts to leave our mark. But a small sign that would exist for a few years, possibly a decade or two while his relatives are still on this earth, then it, too, would go the way all organic matter goes.

There were other graves and stories that caught my attention. There’s the Painted Turtle Man. I might not be getting all the details right, but apparently when he arrived to pick out the spot where his future grave would go, he encountered a painted turtle and decided that was the location where his burial would be. He is buried there, with an etched stone that speaks his truth but does not reveal his name. A real painted turtle — by which I mean live, not a statue as I first mistook it – is also there, right alongside it, and though it moves around, it apparently always returns to that spot. I nearly stepped on it as Ed Sr. was telling me the story.

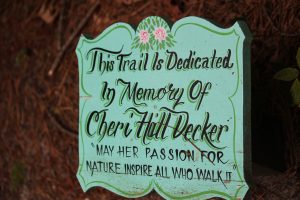

On their web site, there is a short movie that tells the story of the cemetery and preserve, as well as the poignant story of Cheri Hall Decker. Cheri was an environmental educator who worked with the Bixbys and who, when she died from an acute form of cancer, is buried at the entrance to the forest trail, still keeping company this piece of earth she loved and stewarded.

Cheri was a local, but there are people from all over the country buried in this place. It takes some planning, and if you are far away, an airplane ride for a corpse along with a New Jersey licensed funeral director to pick up at the airport, but it’s possible. Not every state or locale has easy access to a treasure like this. Most recently, I was living in Western Massachusetts where such a thing does not exist, though there are people trying to bring a green burial preserve into existence there.

There are some traditional cemeteries that have sections that allow for green practices. You can go to this link and find out if there are some near you. Yet having a full out preserve, where the natural environment is not only maintained, but sustained, is incredibly compelling. It may not be accessible geographically to all, but it is often much more financially accessible. Unfortunately, that it costs less may lead some in the funeral industry to not share information about green options unless asked.

I am new to New Jersey. I do not know whether I will be here when I die. If I am, Steelmantown is where my body should be laid to rest. This is how I want to do it when I die. I want my body to rejoin the earth. I want my people to take part. I want to co-mingle my atoms with soil atoms and leaf atoms and acorn atoms and moss atoms. I want to decompose directly, without barrier.

Hello, I was wondering if I could use some of these images in a video? I’m happy to credit you! Please let me know.

Yes, you are welcome to do so with attribution. Karen G. Johnston