The Unitarian Society

East Brunswick NJ

December 4, 2016

I am a story. So are you. So is everyone. So say the opening words from our Time For All Ages story this morning.

I am, in fact, like you and like everyone, many stories.

Here is one of my many stories. On my first day of social work school – an intensive program of 11 weeks in the summer to complete two semesters’ worth of work, then an eight-month full-time internship in different parts of the country (I did mine in Washington DC and Suburban Virginia) – three summers, two internships, and a masters thesis on grandparents raising their grandchildren.

On the first day I saw a fellow student, a white woman. She was wearing a necklace– a leather choker around her neck and on it were small white conch shells. It was a handsome piece of jewelry, the kind I associate with Africa and with those people I have met who are African American and proud of their heritage.

To this day I still remember my reaction: what is a white girl doing wearing that?!? Apparently, I have an issue with judgment. Inside my mind, a story began to be told about this white-girl-wannabe who went around misappropriating Black culture. I knew already that I did not like her.

As we began to attend our classes, it turned out that she and I had all but one of our classes together, including our practice class, which involved intensive reflection and engagement with each other. As we introduced ourselves to each other, she told her story. She was bi-racial – her mother was African American and her father was German and she had grown up in Germany, which caught my attention from own time of living there.

In that moment, something happened in my brain that had nothing to do with conscious me: this woman – her name is Mareka – became, in a split second, Black. Over time and many conversations, I acquired a more nuanced understanding of her racial identity and she has remained, ever since, as much more in line with who she understands herself to be, a person of color and bi-racial. And, as the universe would have it, we became best friends for that very intense period in our lives.

Even now, I find it curious that at one time I saw her so clearly as white, with no shadow of a doubt, and then, as if with the flick of a switch, I saw her as a person of color and cannot, for the life of me, see how I ever saw her as white. It’s so clear to me that when it comes to race, my brain is operating in a way that my conscious mind has no control over.

~~

I know you did not miss all the blogs, tweets or newspaper articles and commentaries, when the analysis of the voting is done, it’s white people who voted this new reality into being.

White men and white women.

Informally (I won’t use the word, “uneducated;” it’s far too condescending) white people and formally educated white people.

Though implicit bias is a human experience – it does not matter what your social location, whether your identity is one that reflects cultural privilege or cultural marginalization — as a faith community that is predominantly white, sometimes overwhelmingly white, we must pay attention to how implicit bias can play out in dangerous, violent ways.

Today’s reading tells us that fear feeds our acting negatively on implicit bias. Given that we have an incoming president and administration that uses as daily currency explicit hate and greases the tracks of society with fear and manipulation, it is important that we pay attention to how implicit bias may be impacting us in ways we do not know. Our awareness and acknowledgement of it is a first step to establishing the hard path through.

Now, we’ve all been schooled in stereotypes.

We have learned that they are bad, bad, bad.

And we are not to use them.

Or try not to use them.

Which typically results in our pretending they hold no sway over us.

Which leads us to underestimate how much sway they actually have in our lives.

Many of us were taught the being colorblind was the right and honorable thing. We came to feel it in our bones as true when, in fact, it was mere habit. And a bad habit at that.

We were taught seeing color/race is bad, because it can lead to terrible things happening. Simulated experiments have shown non-Black people more likely to shoot Black suspects. Certainly the news reports of Black and Brown men and women being shot disproportionately reflects this terrible reality, too.

So what if it’s not bad to see color, but is, in fact, unavoidable. Unavoidable to see differences of all ilk? Age, weight, ethnicities of varying sorts. What if it is unavoidable to not only see difference, but to attribute a preference, typically one that falls along the lines of cultural oppression: preferring the younger person, more easily associating good with white and bad with Black? Holding a slight or moderate and significant preference for non-Arab/Muslim sounding names?

The science and theory behind implicit bias – what I have called in the title of this sermon being in thrall of our fallen angels, or as the quote on the order of service suggests, in thrall of our primitive brain – is deeper and more comprehensive than the notion of stereotypes. While many theorize about implicit bias, it’s the research of Dr. Anthony Greenwald and his colleagues that is the go-to in this field. They have created scientifically-driven tests – over five million people have taken them, you can too, they are free on the internet – to be able to gauge one’s own implicit bias on a long list of factors.

This is how I spent part of my study leave last week, taking implicit bias tests. Three of them. One based on age – which I thought I would “ace” since I’m married to someone a whole generation older and most of my close friends are at least a decade older than I am and always have been. Yeah: nope. One on Black and white. One on non-Arab and Arab or Muslim-sounding names.

There is no “acing” this test, as if one answer is better than another. The will to take the test is “acing” it: am I willing to face my own shadows, willing to see what the primitive part of my brain has within it, that its power might lessen by my own awareness and by my attending to how these biases play out not only in my mind, by in my actions?

I am telling you this because today’s story by Julius Lester is true and good and one we all like to tell over and over to our children and ourselves: we’re all the same under our skin. This is developmentally appropriate for children of a certain age, for our young ones, but we – youth and adults – need to develop a more sophisticated understanding that holds the paradox of socially constructed race: yes, we are all the same under our skin and yes, we are difference because of the social construction of race and we all exist in a world where there are systems of oppression that benefit some of us and deprive others.

If you are curious or confounded or have questions about this topic, I encourage you to mark your calendars and attend the three-part film series, showing here, called Race: The Power of an Illusion. Each film is about an hour long and there will be a facilitated conversation after each one – thank you Kathy and Reg, our facilitators. Though most powerful if you view all three, and in community with reflection time, if you cannot attend all three, please come to the ones you can attend.

The creators of the implicit bias test suggest that currently, “there is not enough research to say for sure that implicit biases can be reduced, let alone eliminated.” They recommend against most packaged “diversity trainings” unless they are explicitly using evidence-based methods of reducing implicit biases. They encourage a focus on strategies that deny implicit biases the chance to operate, such as blind auditions and well-designed “structured” decision processes.

The creators of the implicit bias test suggest that currently, “there is not enough research to say for sure that implicit biases can be reduced, let alone eliminated.” They recommend against most packaged “diversity trainings” unless they are explicitly using evidence-based methods of reducing implicit biases. They encourage a focus on strategies that deny implicit biases the chance to operate, such as blind auditions and well-designed “structured” decision processes.

But this is not the only word on the subject. There is emerging research – small studies that show promise, but need replication, that there are ways to influence the implicit bias that dwells within us, within our primitive brains.

Quaker sage, Parker Palmer, has some ideas about this, though they are not evidence-based. In his book, Healing the Heart of Democracy, (which is on the book group’s schedule for May and was also part of my study leave), he notes that “learning how to hold life’s tension in the responsive heart instead of the reactive primitive brain is key” to our cultural and democratic survival. He says

Quaker sage, Parker Palmer, has some ideas about this, though they are not evidence-based. In his book, Healing the Heart of Democracy, (which is on the book group’s schedule for May and was also part of my study leave), he notes that “learning how to hold life’s tension in the responsive heart instead of the reactive primitive brain is key” to our cultural and democratic survival. He says

When the primitive brain takes charge we are in thrall to the fallen angels and the outcome is altogether predictable: we contribute to the dynamic of violence that constantly threatens life itself.

Palmer gets more specific but I think you’re going to have to join the book club to find out.

There is some evidence that pairing your acknowledgement of a bias while saturating yourself with real, disconfirming examples that lean away from the bias can reduce the bias, or at least your acting on it. Add to that, developing authentic relationships across difference has shown to also impact behaviors, and possibly bias. We see this in the shifting in America of attitudes towards gay, lesbian, bisexual, and even trans folks – with these people coming out, and families “discovering” that they know someone, has meant one of the biggest and quickest changes America has seen in its civil rights movements. This is part of why I spent the first half of my theological education at a seminary that was thirty percent Muslim. To learn more about this approach, there is an engaging TED talk by Verna Myers that addresses these steps.

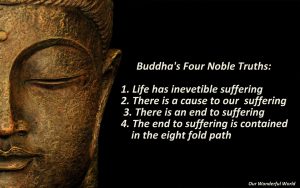

But I want to tell you about what meditation, what mindfulness, with its roots in Buddhism, has to offer. The person known as the Buddha named three truths already known in his time: that life is suffering, that suffering has a cause, and that the cause of suffering can cease. Then he named a fourth, revolutionary truth: there is a path that can cease the suffering. He called it the eight-fold path.

I want to suggest to you that science is beginning to tell us that there is a path – a hard path, a path that requires discipline – out of the suffering of implicit bias. Whether talking about the more general mindfulness, or a more specific meditation practice like the Loving Kindness Meditation, there are some studies – not many, yet – that show this practice reduces automatic processing which is one of the feeders of prejudicial behavior. In simpler words: if we can slow down and watch our mind at work, we might be able to stop our racist, reactive behavior.

I want to suggest to you that science is beginning to tell us that there is a path – a hard path, a path that requires discipline – out of the suffering of implicit bias. Whether talking about the more general mindfulness, or a more specific meditation practice like the Loving Kindness Meditation, there are some studies – not many, yet – that show this practice reduces automatic processing which is one of the feeders of prejudicial behavior. In simpler words: if we can slow down and watch our mind at work, we might be able to stop our racist, reactive behavior.

Recently, in 2014, there was a little (and I do mean little), yet promising, controlled study that found that mindfulness can lessen implicit bias. It involved listening to a ten-minute recording that focused increased their body awareness with the encouragement to do so “without restriction, resistance, or judgment.” Nothing about stereotypes or guilt or shame, just attention to the body and its processes with a generous and open, nonjudgmental heart.

Now, listening one-time to a recording is not going to have lasting effects. This study is saying that the spiritual practice of mindfulness can make a difference. Important here is the word, “practice.” Practice. Over and over. Every day, or at least nearly so. Bringing attention and bringing intention. It sounds simple, and in some respects, it is, but it is oh-so-hard. It is a hard path.

Here is another of my stories. One of which I am not at all proud. In fact, quite the opposite. There are times my brain thinks sh*t that I cannot believe I believe. In fact, if you were to ask me, I would say that I don’t believe it. But I hear my brain sometimes and it has a potty mouth. Mostly I notice it when I am driving, when I am displeased with how other drivers are driving. So it is not fear, but anger, that brings this about. Not only do I have a potty mouth in the form of curse words that I say out loud, but in the form of other things that I dare not utter. They are ugly and too often they are racist or sexist or something-ist.

And this is where my meditation practice has led me: to not turn away from these ugly thoughts the mind is thinking, but to turn toward them. Turning away gives them power; turning towards them lessens their influence. In turning towards them, and doing so with curiosity, not shame, not judgment, and by the very fact that such a mindful stance requires that I slow down, I have discovered something.

I have discovered that there is something before the ugly thought. There is the reaction to being cut off when making a left turn, or having a parking spot taken just as I am about to pull into it. There is the reaction of frustration, of impatience, of anger and it is pure. Then there is a briefest of pauses, barely noticeable by my clumsy human mind. And then enters the ugly thought, like an overlay, like a second thought, like something learned. And thought I don’t like the words that form in my head, the harsh images they evoke, I notice that they are not core of my reaction, they are something secondary, something added, something learned.

This gives me a sense of hope that I am not they and they are not me and that I might be able to exercise some ability to reduce their influence on me and my behaviors. This gives me a sense of hope that I might not have to be in thrall of my primitive brain or my fallen angels. None of us do.

May we learn to quite the noise of implicit bias so that we can truly hear our own story and each others’. May we find the courage and the perseverance to listen to the angels of our better nature. Amen. Blessed be.