The Unitarian Society, a Unitarian Universalist Congregation

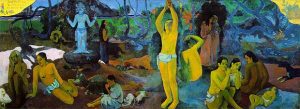

When I say the painter’s name, Paul Gaugin, does your mind draw up images of his work? Sumptuous tropical scenes. Tahitian women. A contemporary of Degas and Van Gogh, he was an influence on Picasso and Matisse, though not widely known during his lifetime.

Gaugin considered the last painting he completed, which depicts three stages of life, from birth to death, his best. Of it he once said, “I believe that this canvas not only surpasses all my preceding ones, but that I shall never do anything better—or even like it.” On that canvas, he wrote these three phrases:

Gaugin considered the last painting he completed, which depicts three stages of life, from birth to death, his best. Of it he once said, “I believe that this canvas not only surpasses all my preceding ones, but that I shall never do anything better—or even like it.” On that canvas, he wrote these three phrases:

Where do we come from

Who are we

Where are we going

These are written in capital letters and without punctuation, though it seems nearly impossible for the mind not to place a question mark at the end of each set of words.

In the teal hymnal, Singing the Journey, which is widely used in Unitarian Universalist congregations, though not here (yet), there is a hymn. The music written is by Brian Tate, inspired by those three phrases. It goes something like this:

In the teal hymnal, Singing the Journey, which is widely used in Unitarian Universalist congregations, though not here (yet), there is a hymn. The music written is by Brian Tate, inspired by those three phrases. It goes something like this:

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Mystery. Mystery. Life is a riddle and a mystery.

I worry that some forms of our dogged Unitarian Universalist commitment Reason cuts us off from the power and benefit of that mystery.

***

The first time I encountered you, dear congregation, it was last December. I was sitting with my laptop computer in my home office in Florence, Massachusetts, reading what is called the Congregational Record. This is a document that your Ministerial Search Committee carefully crafted as a way to describe you, following a standard format that all congregations in search had to follow. In this Congregational Record, there were many clues about who you are, who you think you are, who you wish you are, and who you wish you can become.

There was commentary about the theological diversity among individuals here. Here are some statements from this document in that regard:

As UUs, we are theists, atheists, humanists, Buddhists, and for some, a combination of any of these and more.

and

The minister we aspire to find is one who is aware that while individuals in our congregation have much in common, due to the wide variety of beliefs held by our congregants, it can be challenging to forge spiritual connections among our membership.

And, in response to the question on the form, “What congregational issues may never be resolved?” there was this response:

Reconciling our diversity of beliefs with our desire to be a cohesive community. Part of this is recognizing that specific language with religious connotations can be problematic for those with varying beliefs and backgrounds.

Since then, including last May and Candidating Week, and in the nearly eight weeks since I arrived as your Called Minister, I have gained a greater, but by no means complete, understanding of just what your theological diversity is and how it influences congregational life here.

I have seen the richness it brings, evident by the painting that greets everyone who enters the building and in the words you claim and try to live into: from your founding days, the Bond of Union. The theological diversity here gives impetus to actions and words that honor those who understand themselves as seekers, knowing that we are all on a path of seeking and finding and in doing so, no one betrays codified dogma here. It is a place where the author of one of our readings, who considered herself a “terrible believer in things and a terrible non-believer in things” would feel right at home.

This theological diversity has other shapes here. Some of them curious. For instance, you have not a Worship Committee, but a Sunday Services Committee – yet you have Worship Associates. I have heard stories of strong reactions about the theoretical possibility of stained glass – regardless of the image – and whether such things would make this place “too churchy.” Newer members have shared with me worries about offending if they were to call this place “church,” even though it is what best reflects their lived experience.

These things are yours to own and address. And they are a legacy of our ongoing Laboratory of the Spirit, a term I borrow from the Reverend Jason Seymour, who spent his first six years of life in this congregation. In this Laboratory of the Spirit we Unitarian Universalists married humanism and theism, married science and faith, believing that these can not only co-habit together, but can enrich and embolden each other, embodying a religion needed desperately by this aching world.

I have faith in this particular marriage. And I know to be true that, like every married or cohabitating couple, the differing perspectives can be a source of irritation.

Sometimes more that mere irritation: congregations can dip into the realm of conflict, dysfunction, and spiritual stagnation, some living out their collective lives there. I am thankful that TUS is not one of them.

Theological diversity is definitely here. In the nearly two months I have been here, I have spoken with some of you who decisively declare yourselves to be atheist. And I have spoken to some of you for whom not only is god an essential part of your life, so is Jesus. And I have spoken with others who neither reject nor embrace theism. And there are many who understand yourselves as Buddhist. And I have spoken with some of you who feel you the best descriptor for you is “agnostic.”

And while “reconciling the diversity of belief” may be never resolved as your Congregational Record described, perhaps that is the wrong goal. How about rather than casting it as a problem needing solving, how about we see it as capacity that requires cultivation and ongoing attention. From my experience, a lack of ongoing attention to how to live together in the midst of theological diversity can heighten some of the more unsavory aspects of a shared religious life – like conveying an unwelcoming attitude even when we do not mean to. We at TUS have work to do in this realm not necessarily because there is a problem, but because this is one of the legacies of a marriage that was chosen by our religious forbears and into which you were born or adopted or somehow joined up.

Towards this end, I want to talk today about a useful tool that can sometimes become a weapon: skepticism. My guess is that many of us use some form of skepticism to get through your life. Of course you do. How about skepticism when viewing commercials on television? How about when listening to political discourse? What about when it comes to religious beliefs?

Skepticism belongs to our Unitarian Universalist religious experience. It’s the contribution of our nineteenth -century Unitarian ancestors who understood themselves to be Christian while adopting reason to interpret the Bible. This led to the interpretation that there was no scriptural basis for the trinity (hence they earned the name Unitarian, which was at first a slur, until they claimed it as their own). The Unitarians also reasoned that Jesus was not born of god, and thus not divine (not any more than anyone of us, I suppose). He was a human teacher, a social revolutionary, worthy of emulation, not worship.

A more modern iteration is the fourth of our seven principles. Not a quiz: knows what our fourth principle is?

A free and responsible search for truth and meaning

Free means we are not bound by religious dogma and responsible means that we are expected to use reason (and I believe, other traits, like curiosity, compassion, and humility) on our search.

Though reason and skepticism belong to our essential religious identity, there are times when it veers from a responsible form to what I consider an arrogant one. Much to my sadness, I have observed this enacted in many UU congregations. And so have many of my colleagues. If you have been around Unitarian Universalism for any length of time, you, too, have likely seen it in action. Sometimes, and perhaps this is true for you too, I have seen it in my own soul.

Arrogant skepticism is laced with more certainty than actual engagement. Someone is already sure of their opinion, but uses the window dressing of skepticism to appear otherwise. While there might be a stated intention of mutual respect, arrogant skepticism comes off more like thinly-disguised condescension and can be quite ugly, often without the person even aware of their own smugness.

We UUs are not the only humans who exhibit this imperfection. But ours takes a particular form that impacts our shared lives and for which we alone are responsible. I believe that one of our religious gifts to the world is how to live well together in the midst of disparate beliefs. Our lived practice and theological commitment makes us exquisitely well-suited to interfaith engagement, if only we are aware and intentional and practice what we preach. I believe we can do better, each of us individually, and all of us as a whole.

The Israeli writer Yehuda Amichai has a poem that evokes for me the troublesome nature of this arrogant form of skepticism, as well as suggests its antidote. The poem is called, “The Place Where We Are Right”:

From the place where we are right

flowers will never grow

in the Spring.

The place where we are rightis hard and trampled

like a yard.

But doubts and lovesdig up the world

like a mole, a plough.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

where the ruined

house once stood.

The poet tells us that doubts and loves, along with a whisper, are what save us from the barren, hard landscape of certainty or arrogance.

For me, this doubt is holy skepticism.

For me, this love is faith.

For me, that whisper is mystery.

***

One of my most beloved go-to sources for reflecting upon the intersection of science and faith, reason and religion, is Chet Raymo, professor emeritus of Physics, prolific author, and former columnist for the Boston Globe. The titles of his books – many of which are on the shelves in my office – include Honey From Stone: A Naturalist’s Search for God; When God is Gone, Everything is Holy; and Skeptics and True Believers: The Exhilarating Connection between Science and Religion.

Raymo uses the word “learning” to describe the science side of things and “yearning” to describe the faith or religious side of things. Here is what he has to say about learning (science) without yearning (faith):

Learning without yearning is pedantry, scientism, idée fixes. Learning without yearning is believing that we know it all, that what we see is what we get, that nothing exists except what can be presently weighed and measured. Learning without yearning is rote without a heart, without a dream, without a hope of beauty.

He goes onto say

Skepticism by itself is sterile. Skepticism by itself can be arrogant. Skepticism by itself can close the door to new experience.

Since skepticism is essential, but alone is not enough, then what else is necessary? Raymo suggests pairing it with the philosophical rule of Ockham’s Razor: the simpler explanation is usually the more accurate one. That makes sense coming from him. But it does not fit our religious circumstances as well as I would like.

Since skepticism is essential, but alone is not enough, then what else is necessary? Raymo suggests pairing it with the philosophical rule of Ockham’s Razor: the simpler explanation is usually the more accurate one. That makes sense coming from him. But it does not fit our religious circumstances as well as I would like.

Rather than Ockham’s Razor to pair with our particular form of skepticism, I want to suggest that as Unitarian Universalists – as liberal religious folk — we should pair it with reverence.

Just what is reverence? It is the experience, the capacity for which can sometimes be developed, but oftentimes comes unbidden, that makes us want to weep, to dance, to fall to our knees filled with a longing to be one with whatever is evoking this response. It is the urgent impulse to sing or SHOUT or whisper everlasting praise. It is spontaneous hallelujah bubbling out of your mouth up to the sky. It is deep belly laugh that comes unexpected and must run its course. It is awe that does not bring comfort, but cleanses the soul’s palate for what is next to come. It is finding yourself praying when you did not know that you pray. It requires no supernatural explanation and is as visceral as physical hunger, as sexual longing, as trembling fear. At its best, though it might remind us how small we are in the vastness of the cosmos, reverence awakens within us a sense of belonging and connection, our place in the universe.

One of our foremost humanist ministers preaching and ministering today, Reverend Kendyl Gibbons, says this about reverence and skepticism:

We are not skeptics because nothing is sacred. No, we withhold our assent to unproven claims because integrity matters, because the real experience of reverence is so primal and so powerful that it must not be captured and exploited for lesser purposes. …

Indeed, the foundation of all ethics is to be loyal to the truth we know, to the justice and mercy we cannot help but love. How do you become that person, the one who rises intuitively to the demands of the good, who lives in the heaven of the present, who is fed by the beauty of creation? Not, it seems to me, by abandoning skepticism; not by taking someone else’s word for what life means and how we are supposed to live. The skeptic’s path is its own journey, and it can be just as rich in reverence as any more conventional religious structure.

***

In the world of interfaith engagement, there is a set of guidelines I was taught while attending seminary where thirty percent of the student body and faculty were Muslim. The late Krister Stendahl, Dean of Harvard Divinity School and later Bishop of Sweden, proposed a framework with three rules, the last of which was to practice “Holy Envy.”

Moving beyond just tolerance or respect for aspects of another faith tradition, Holy Envy brings us into deep, authentic appreciation. Remember that commandment that says do not covet? Well, Holy Envy suggests that if it’s not your neighbor’s spouse, but is some aspect of your interfaith partner’s faith tradition, then it just might be a good thing. Perhaps with this rule as our inspiration, with equal parts reason and reverence we can turn our skepticism into Holy Skepticism.

Yes: let us make our skepticism holy. Let us infuse it less with disbelief and more curiosity. Let us abandon our intellectual cynicism and need for being right and suffuse our skepticism with a sense of possibility. Let us remove completely the arrogance that sometimes seems to infiltrate and let us immerse it in humility. Let us attune ourselves to the danger of condescension, starting first with ourselves. Let us have our skepticism be wildly laced with reason, abundantly saturated with reverence.

May our heartminds ever be able to see the elephant inside the boa constrictor.

Blessed be. Amen.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Where_Do_We_Come_From%3F_What_Are_We%3F_Where_Are_We_Going%3F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Gauguin#Death

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chet_Raymo

http://www.uuworld.org/articles/primal-reverence